It was only after her death that I really got to know her — through hundreds of online product reviews.

When my Aunt Esther died in the summer of 2011, we knew we’d have to deal with her apartment—specifically, the floor-to-ceiling Amazon.com boxes that filled every room.

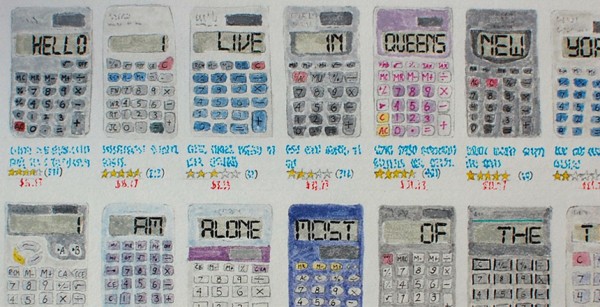

The job of cleaning fell to my brother, who was living nearby at the time. He spent months repackaging unused items, all the while reporting back on the tragedy of all this stuff. Why did she need hundreds of pocket calculators? Or dozens of books on beating the odds at the casino?

Why, indeed?

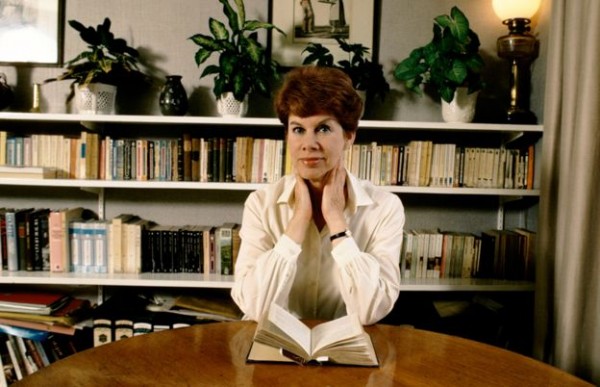

The first Amazon review I encountered by Patricia “A Reader” was in 2007. It was an earnest, paragraphs-long piece about an old picture book. I was reading the review because that very book had just been gifted to my daughters by Aunt Esther. It took a few reads before I realized that Patricia and Aunt Esther were one and the same, but I kept my discovery to myself, filing it away as just one more strange fact about her.

It was only after her death that it became clear my quirky, shut-in aunt had been writing long-form Amazon reviews of everything from books, to pocket calculators, to ice cube trays, to boxes of sugar. And I became her most dedicated reader.

Here is the opening to a 2007 review by Patricia for a one-handed can opener—an item that has sadly long since been off the market:

I presently live in a “no-pets” building – which has its advantages and disadvantages. The “One Touch Can Opener” –- though obviously an inanimate object – can easily be a “pet-substitute”, as well as an excellent can opener! For, as it zips around your can, opening it, it makes a nice little “wiggle motion”….almost like a fish in the water!

The title of this review is:

“A N D…..I T….O P E N S…..C A N S,…..T O O !,”

Certain obsessions become clear when scanning through the more than 700 reviews posted by Patricia between 2004 and 2011. Among them: Alien Nation (the TV show, “NOT the film”); coasters and mugs featuring the British royal family; books on beating roulette in the casinos by use of pocket calculators; pocket calculators; canned fish; and candy bars. It also seems Patricia was either unable or unwilling to purchase many of the items she was reviewing, as evidenced by this late-career review of the film “Lesbian Vampires”:

This movie is full of blood, gore, and lust. (Not that I have seen it…I’ve read other people’s reviews). It has only one redeeming value, in that, (by and large), it must usually keep its viewers inside either their homes or their friends homes….and OFF THE STREETS! …I have a very strong suspicion that it insults both REAL lesbians, and, (IF they exist), real vampires as well.

But Patricia’s crowning moment as a reviewer was when she stumbled across a novelty item in the form of a can of Unicorn Meat. I can only imagine she came to the item while searching Amazon for other actual canned meats. Patricia is both outraged and disgusted by this product, and does not hold back, giving it two stars out of five:

Now, I am definitely NOT a vegetarian. Yes, I am a proud and happy omnivore, (eating non-meat products as well as meat), and even eat……VEAL!

However, I draw the line at Unicorn meat! These rare and beautiful creatures, if they indeed do exist, should NOT be killed and /or eaten! At least, not till we have a good, authenticated herd of 1,000 or so unicorns around! And if this is only a toy, it is still teaching children, (and adults), a very bad lesson.

There is considerable debate in the three pages of comments on this particular review as to whether Patricia is writing a “spoof” review. Patricia baffles her detractors, and in the end she pulls rank on them all.

“you can’t write over 600 reviews for Amazon, and over three thousand musical pieces — all, alas, presently unpublished — without being sensitive”

The tone of Patricia’s reviews is always hopeful, and thoughtful. For me, this is a window into Aunt Esther’s world, one that I was rarely privy to in our brief personal interactions. In her first review, Patricia discusses her sometimes fraught relationship with her more worldly sister, my mother, by celebrating their shared love for a book on class and status. Elsewhere, she discusses her childhood, her loneliness, and her desire to be useful, to be needed.

Yes, she was searching the endless options available on Amazon.com for the perfect pocket calculator. But I think she was searching also for the sake of sharing her discoveries with her adoring readers, even if that group was only just me.

In the months after she died, I read and reread each of Patricia’s reviews. Only then was I able to do the thing I wished I had known to do when she was alive. “Was this review helpful to you?” Amazon asked me at the end. Yes. Yes. Yes.

Complete Article HERE!