It was a scandalous topic before Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne in 1876.

“Things were a little ghostly,” wrote a reporter for the Philadelphia Times, setting the scene for a morbid public spectacle. The press had been invited to the first “modern” cremation performed in the United States. It was December 6, 1876.

The Times reporter was among a crowd of journalists and townspeople gathered at the top of a hill in Washington, Pennsylvania to witness the first run of a new crematory built by Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne. The furnace, designed by LeMoyne and built on his own property, was based on a working model presented at the Vienna Exposition in 1873. The remains to be cremated were those of Joseph Henry Louis Charles, Baron de Palm, a Theosophist who was fascinated by “Eastern” philosophy, and besides that had once known a woman who had been buried alive, and was terrified by the prospect.

Burning the dead is an ancient practice, and in some cultural traditions, it’s a thousands-year-old norm. Today, cremation in the U.S. is soaring in popularity; by 2018, the Cremation Association of North America predicts that over 50 percent of Americans will choose to have their bodies cremated.

But in late 19th-century America, cremation was a radical, tradition-bucking idea. LeMoyne and other cremation advocates believed that burying the dead in the ground allowed germs to seep into the soil, thus contributing to the spread of diseases like cholera, typhus, and yellow fever. Cremation promised to sterilize human remains and bypass the altogether slow and icky process of decomposition. When performed in a state-of-the-art indoor furnace, it was a sanitary and high-tech alternative to burial.

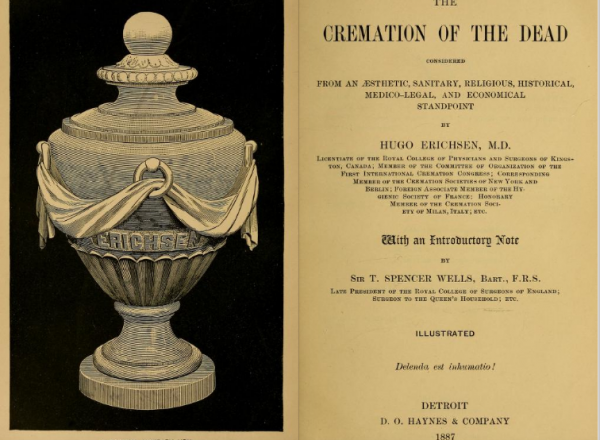

Cremation was also a solution to an urban problem. As cities expanded, they surrounded burial grounds that had once been miles away from town—and rested on prime real estate. “In and about New York, Brooklyn, and Jersey City, 4,000 acres of valuable land are taken up by cemeteries,” wrote Hugo Erichsen in his 1887 pro-cremation treatise The Cremation of the Dead. “It is calculated that with the probable increase of population in the next half a decade, 500,000 acres of the best land in the United States will be enclosed by graveyard walls. … It is an outrage!”

But cremation didn’t catch on with the masses right away. LeMoyne had first approached a local cemetery with an offer to build the crematory on their land; they dismissed him with disgust. The Times reporter who witnessed the de Palm cremation was horrified: “If [de Palm] could have foreshadowed the startling scenes his poor bones would have to go through he would have thought twice before he jumped into the fire.” Anti-cremationists put aside their religious discomfort with cremation to argue that burning bodies would encourage crime—you can’t exhume a cremated corpse!—and dismissed the public health claims of cremationists as unfounded fear-mongering. (They weren’t wrong; there’s no evidence that in-ground burial encouraged the spread of epidemics.)

Cremation was also a solution to an urban problem. As cities expanded, they surrounded burial grounds that had once been miles away from town—and rested on prime real estate. “In and about New York, Brooklyn, and Jersey City, 4,000 acres of valuable land are taken up by cemeteries,” wrote Hugo Erichsen in his 1887 pro-cremation treatise The Cremation of the Dead. “It is calculated that with the probable increase of population in the next half a decade, 500,000 acres of the best land in the United States will be enclosed by graveyard walls. … It is an outrage!”

But cremation didn’t catch on with the masses right away. LeMoyne had first approached a local cemetery with an offer to build the crematory on their land; they dismissed him with disgust. The Times reporter who witnessed the de Palm cremation was horrified: “If [de Palm] could have foreshadowed the startling scenes his poor bones would have to go through he would have thought twice before he jumped into the fire.” Anti-cremationists put aside their religious discomfort with cremation to argue that burning bodies would encourage crime—you can’t exhume a cremated corpse!—and dismissed the public health claims of cremationists as unfounded fear-mongering. (They weren’t wrong; there’s no evidence that in-ground burial encouraged the spread of epidemics.)

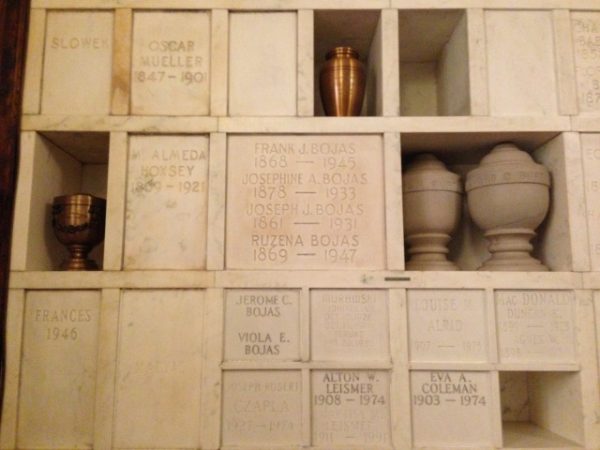

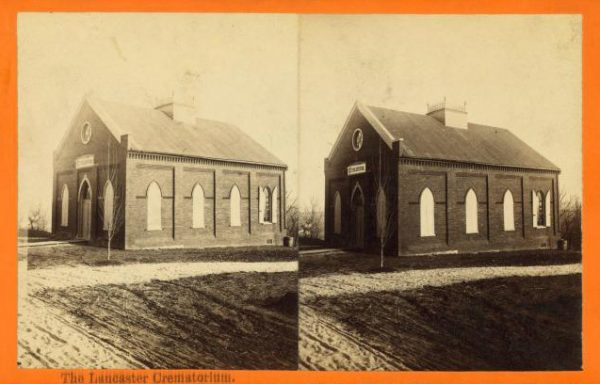

Throughout the 1870s and ’80s, as debates about cremation raged in the papers, local cremation societies were organized to argue their case and — more importantly—to raise funds to build crematories. The first public crematory in the U.S., at Lancaster, Pennsylvania—funded by the Lancaster Cremation and Funeral Reform Society—was built in 1884. By 1887, Cincinnati, Buffalo, Los Angeles, and Detroit had all built crematories, many of them designed to look like chapels, with stained glass and stonework. These crematories operated independently of cemeteries, which saw cremationists as competitors.

A few of these early crematories still exist; in Cincinnati, the building is hiding behind deceptive new construction.

Sometimes the dead traveled hundreds of miles to have their last wishes fulfilled. When Barbara Schorr died in Millersburg, Ohio in 1887, her family honored her wish to be cremated by sending her body to the Detroit Crematorium—nearly 200 miles away, it was nonetheless the closest crematory. But it was still under construction, so Barbara Schorr lay in state for several weeks while it was completed.

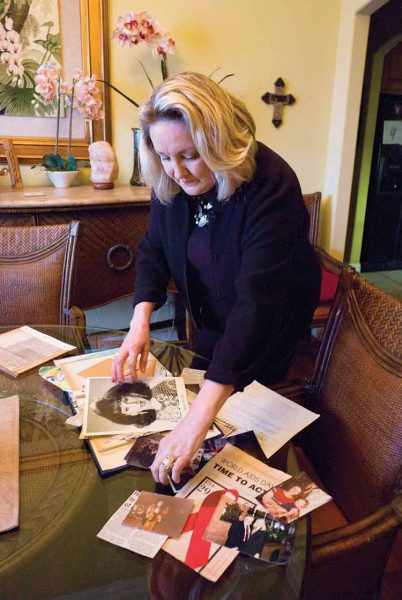

Today, a portrait of Barbara Schorr, commissioned by her sons, hangs in the columbarium at Woodmere Cemetery, honoring her as a pioneer of the cremation movement in Detroit.

Because cremation was a moral crusade for the betterment of public health, it attracted sympathizers from other moral causes to its ranks, including no small number of women activists. The suffragist Lucy Stone was the first person cremated at the Forest Hills Crematory in Boston in 1893. Frances Willard—suffragist, temperance activist, and avid bicyclist—was also a vocal advocate of cremation. In 1900, the New York Times ran a satirical news item about the cremation of Willard’s cat: “Each of Toots’s human friends will sprinkle a little myrrh or frankincense over the body, and while it is being consumed the incense will counteract any odor which might be emitted through the furnace chimney.”

By the early 20th century, the sensationalism of cremation had waned, and the practical case for cremation was winning minds. After all, cremation, which requires no elaborate monument marker or plot purchase, is significantly less expensive than in-ground burial. Eventually, cemetery directors realized they might be better off joining the cremationists than trying to beat them. In 1899, Mount Auburn Cemetery—famously one of the original rural cemeteries in the U.S.—hired an architect to renovate an existing chapel on the grounds into a crematory. It was the first cemetery crematory in the state of Massachusetts, and it marked a turning point in the history from what was once a “ghostly” spectacle to an agreeably American way of death and burial.

Complete Article HERE!