By Morty Portaro

For something that literally happens to everyone, death is a remarkably taboo subject in American culture. It makes some sense, though. Who wants to think about the lights going off permanently, let alone deal with the actual logistics of dying?

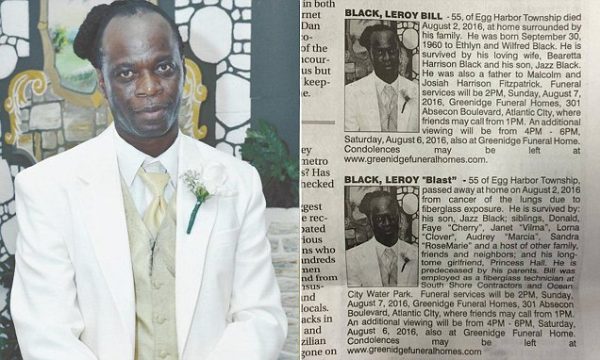

That’s why I’m here. I’m a funeral director. I help you with the things you don’t want to deal with. No, it’s not exactly like Six Feet Under. Yes, you have to go to school to be a funeral director, at least in New York State. Everybody always seems surprised when I tell them that — maybe they think any guy selling bootleg Yankees hats off the street could throw on a suit and start handling funerals and grieving families.

That’s ridiculous, for a lot of reasons. Not only are you dealing with dead bodies, which, beyond being frightening to most people, can also be host to all kinds of diseases, but there’s also the governmental red tape and transactions that could see tens of thousands of dollars changing hands. It’s certainly not a career someone could jump into blindly and excel at… especially given some of the situations I encounter regularly. These are just a few slices of what it’s like to be a New York City funeral director, one of the most overlooked, but essential, careers a person can have.

A normal day is never what YOU think of as a normal day

>For starters, I want to clear something up: every now and then I’ll run into someone who thinks it’s crazy that funeral directors charge money for what we do. It’s not. We do the job that other people can’t or won’t do. We provide a valuable service to the community. We’re not looking to rip you off, we’re just looking to be compensated for the work we do. Most people don’t have to deal with questions about whether they should make money in exchange for working hard, but death can elicit some strange behavior in the living.

My normal workdays are filled with events most people won’t ever experience in their lives. Picking up and tending to dead bodies, dealing with grieving families, taking funerals out to churches and cemeteries. To put it into perspective, remember that day at work when you spilled coffee on your pants and had to walk around with a huge stain all day? Well, my version of that involves throwing out a white shirt I was wearing because body fluid got all over it. The body fluid wasn’t mine. Yeah.

But, just like you, I have massive amounts of paperwork I have to do. After all, a job is a job is a job.

Hopefully you won’t have to attend too many funerals, but if you live long enough you’re almost certainly going to have face the music at least a few times. They’re rarely pleasant (except jazz funerals. Everyone should experience a jazz funeral — that’s how I want to go out.) but they’re a reality, and when you do have to go to one, there are a few things to keep in mind that will make your experience — and the funeral director’s — much better.

There’s no official dress code, but don’t push it

I understand that this nation is experiencing a full “dressing-down revolution,” but let’s evaluate. If you’re a male family member, a suit is almost a must. If you can’t wrangle a suit, slacks and a button-down are acceptable, but try not to dip below that. Polos are borderline and T-shirts are damn near disrespectful. I saw a guy walk into my place wearing an Angry Birds shirt, jorts, and Crocs. You’re going to a funeral, not a taping of Monday Night Raw. Put some effort in.

As for the ladies, just look nice. You have a few more options than the guys, but make sure it’s nothing too crazy, and NO JEANS. I swear I once had a lady walk in for a wake wearing a bikini and a cover-up that didn’t quite “cover up.” I assure you that anything you can wear to the beach isn’t appropriate to wear while standing in front of a casket. You don’t have to be a MENSA member to understand this.

Funerals are not the time or place for a buffet

In New York, we can’t have food in the funeral home. This isn’t just our rule, it’s also the New York State Board of Health’s rule. Food attracts bugs, vermin, and other unwelcome guests into funeral homes. We know this. The Board of Health knows this. The sign in our lobby is there so you know it.

This doesn’t mean “all food except the three dozen donuts and a box of coffee.” This isn’t Golden Corral. You should be able to handle going two or three hours without food — it’s why most wake times are split up, so you have a couple of hours for dinner in between.

One day somebody tried to bring in four pizzas and a case of beer for a wake. I was tempted to let him in, because who doesn’t love pizza, but I had to stop him at the door. This led to my being cursed out in vile, creative fashion, but hey, those are the rules. And really you should know that pizza is only acceptable at a wake if it’s for one of the Ninja Turtles or Kevin from Home Alone.

Drinking, death, (and sex) go hand in hand, but know your limits

A lot of people need a nip or two to get through a funeral. It’s stressful, and sure, you might want to take the edge off. DO NOT DRINK TOO MUCH. Too many times I’ve witnessed people puking all over the bathrooms here. Years from now, you never want to hear the question, “Hey, remember at grandma’s funeral when you did seven tequila shots back to back at dinner and vomited into a potted plant?”

Things can get even dicier when sex is added to alcohol — death and sex have long been connected in art and literature, a truth I see lived out more frequently than you might expect. I had a funeral for an older woman who had a granddaughter about my age. The granddaughter was involved in the funeral arrangements, and during the afternoon visitation, everything went smoothly. As she was leaving, she invited me to a bar to join her for drinks between sessions, but seeing as I had to work the night session of the wake, I declined.

Well, when she got back from the bar she was bombed. Staggering all over the place, knocking a plant down, slurring her words. It was bad. She mentioned something about needing to talk to me, but I blew her off, chalking it up to buzzed babble. When she disappeared for a while and the ruckus seemed to die down, I decided to slip off to my office to decompress.

Once I turned the light on, I saw that she was in there, sleeping. I woke her up (more or less to make sure she wouldn’t vomit in there), and she immediately clung on to my chest, talking about “wanting to thank me.” That hand on my chest surely made its way down to my crotch, and she was not letting go, despite my protests.

At that point, I knew I had to get her out of my office and off of my crotch, since no good could come out of this situation. I started to steer her out of the office by her shoulders while she began kissing my neck, making it out into the hallway. Luckily, one of her cousins saw me and pulled her away, and someone drove her home after that. At her grandmother’s service the next morning she couldn’t look me in the eye. Only after the casket was lowered did she come up to me and apologize.

Funerals are times for mourning, not violent grudge matches

Emotions run high enough during funerals, so don’t make things worse by continuing old grudges or starting new ones. One bad exchange can set off a powder keg.

I witnessed two brothers squabble over money from the minute they came in to make arrangements. The morning of the funeral it reached its breaking point. What started as a loud argument in front of the casket progressed to a screaming match in the lobby.

By the time I got to them I couldn’t believe what I was witnessing — each brother was holding an unplugged floor lamp like a lightsaber, circling each other. It took me a second to process everything, but when I finally spoke up to tell them how ridiculous the situation was, one them smacked the other over the back with the lamp (I do have to respect the opportunistic nature of that fella), which led to a quick skirmish on the floor. It broke up pretty quickly, but it was neither the time nor the place for it — the correct time and place would’ve been the ECW Arena in 1997 — and everybody left feeling pretty embarrassed.

If you’re not hammered, violent, or blatantly rule-breaking, most other requests are OK

On the other side of the coin, if you have a special request for your loved one, don’t be scared to speak up. One person wanted me to play Nirvana on the way to the cemetery because it was the deceased’s favorite band. “Oh, and one more thing — CRANK IT.” You bet your ass I did it. There wasn’t a cooler hearse in the world that day. It got some strange looks from the people we passed on the street, but whatever.

I’ve received requests to wear a Mets tie while doing a funeral, to pass someone’s favorite bar on the way to the cemetery, to lead an entire collection of people attending a funeral in singing The Golden Girls’ theme, pretty much anything you can imagine. Have I rolled my eyes at some of the requests? Absolutely. But you know what? When you see how much it means to the family, it makes it all worth it.

People don’t really want to talk about death or funerals, and yeah, funeral directing is a strange job. Having your mortality thrust in your face every day you go into work gives you a pretty unique outlook on life. I don’t particularly mind the job as a whole — I wish it were more 9-5, but hey, I get to help people, and that feels pretty good.

Complete Article HERE!