As people search for ways to reclaim death from the funeral industry, a home vigil can help with the grieving process

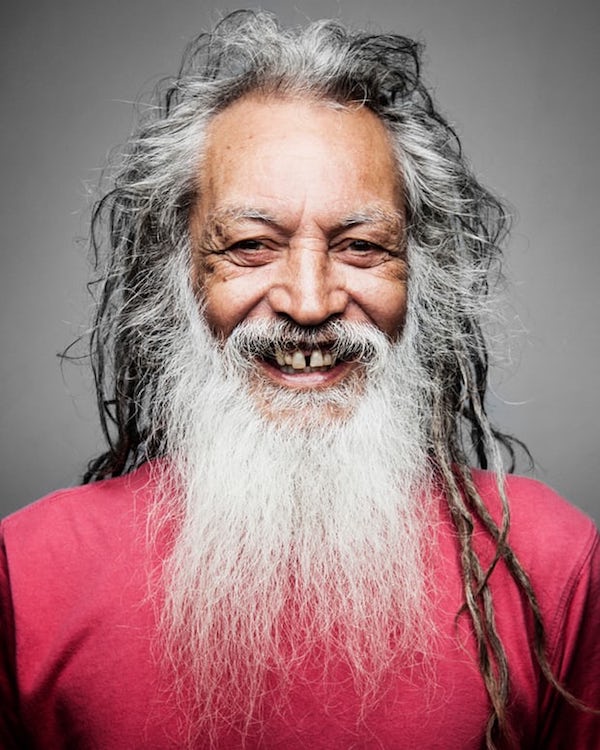

[P]ete Thorpe was a wiry, strong and vital man. He loved his children, his wife, Fiona Edmeades, and the home they shared in Bondi. At 69, he was a well-known local character who was regarded with great warmth by all who knew him.

In early October he was laid up with stomach flu. It struck and didn’t budge for two days. Everyone expected that he would be back on his feet by the weekend. But on the evening of the third day – a Tuesday – Thorpe died suddenly of a heart attack.

“It was the last thing on earth … ” Edmeades explains, looking out of the window of their flat into the treetops, searching for the language to convey the shock of how her life had ruptured. “He just died.”

In the chaos of the hours that followed that moment, she knew one thing – Thorpe was not going anywhere.

“I knew I wanted to keep him with me,” she says. “Pete was Māori so that is the tradition in his culture – I had attended a couple of tangis so I knew it was possible.”

The tangi is a Māori death rite that involves close and extended family remaining with the dead for three days to mourn and honour them. “I just felt there was no way they could take him away,” she says.

Edmeades’s GP wrote a death certificate for Thorpe that night, which meant his body didn’t have to be taken away to the coroner’s. He could stay in the flat with his family, under New South Wales regulations, for five days.

He remained there until Friday afternoon. He was mourned at home and his funeral, organised by local funeral directors, was held there. Friends visited the flat and cried for him and told him jokes and sang songs and slipped small gifts into his hands. Extended family decorated his coffin in the back garden. Edmeades and their children placed him into it and sealed the lid themselves. They drove him to the crematorium and accompanied his coffin to the furnace door.

Edmeades says having him at home with her, their children and friends, helped her to process his death. It helped her face up to the fact that he was gone, especially because his death had been such a shock.

“As hard as it was to look at Pete and see it wasn’t Pete any more, it is just his body, it was so much less hard than having him disappear – poof,” she says.

“To be able to understand it in your body on a physical level means you can free yourself from the denial. Seeing that lifeless body is how you come to terms with the death and if you can’t come to terms with the death, how can you grieve? It would have been so traumatic if he just disappeared.”

Instead of Thorpe’s body being taken away that night to lie alone in a morgue or funeral home, Edmeades made a bed for him in the sunroom adjacent to their bedroom. It was his favourite room in the house and, with him there, she and her daughter could lie on their bed on that first night and see him.

“I was able to look at him all night and slowly understand the changes and that things had changed. He was still there and I could see him but the change was real, in such an unreal time.

“I would doze and then wake up and there was this wave of feeling utterly lost, but then there was Pete, anchoring me back in the world.”

The family’s story is becoming more common, as people decide to take death, dying and the days after death away from the medical and funeral industries and back into their own hands and homes.

Victoria Spence, an independent funeral celebrant and death doula, has noticed a groundswell of people in Australia over the past decade wanting to reclaim death for the family and the community.

Spence has worked with the dying, their bodies and the people they leave behind since the 90s when her father’s terrible funeral – the celebrant repeatedly got his name wrong – inspired her to train as a counsellor and civil celebrant specialising in end-of-life and after-death care.

She has seen communities transition from the need to whisk the dead away, hide them in a box inside a funeral home and then bury them in the ground like a secret. Instead she empowers the bereaved to bring their dead home from the hospital, wash them, dress them, hold their hands, talk to them, play music, build their coffins and hold their funerals in the community centre, school or living room. Taking death back in this way can set the groundwork for healthy grieving, she says.

“People feel alienated by the medicalisation, professionalisation and corporatisation of dying that has taken place,” she says. “Death has become a cultural blindspot for us and people want that to change.”

It is a sentiment echoed by Prof Ken Hillman, author of A Good Life to the End, who argues that death has become the new taboo – like sex was in the 1970s.

“We only talk about [death and dying] in hushed tones,” he writes. “The subject of death and dying need to be brought into the open. There will be so many benefits for us as a society and individuals. Death loses its power over us when faced matter of factly.”

But dealing with death matter of factly is not always straightforward.

Often the thing stopping the bereaved from keeping their loved one at home is the lack of preparation and knowledge about what comes next, Spence says. Fear of the changes that take place in a dead body is also a potent deterrent.

“There is an increasing desire but not the knowledge to help people get ready and get the equipment,” she says.

The most important part of equipment for someone wanting to keep a vigil at home is the cool bed, a stainless steel plate that goes underneath the dead body and is usually set at 1C to 5C, keeping the corpse stable by slowing decomposition.

“Our dead change,” Spence says. “The body stiffens, the skin changes, there can be swelling and leakage. The cool beds slow down all of these processes, you get into a state of stasis.”

Once the bed is installed, Spence says, “It is very comforting to hang out with the body for a couple of days. Nothing untoward or scary happens.”

People holding vigils are often surprised at how peaceful and beautiful the dead are, she says.

Fiona Edmeades worried about all of this when Pete Thorpe died. But a close friend knew about the cool beds and the funeral home organised one.

“The cool bed changed everything because it reduced the aspect of the unknown and the fear that comes with it,” she says. ”Here is this amazing device that enables you to do what you want to do. It just feels so natural.”

Over the three days after Thorpe’s death, their home filled with friends and family. At first, some were hesitant to see him but their reticence always gave way.

“Lots of people who hadn’t seen a dead body before came. One child came and asked, ‘Can I touch him?’ and we talked all about it. When you are in it, it is so natural and gentle and beautiful – it is a beautiful way of saying goodbye.”

For her, having Thorpe at home, and a river of people wanting to come and show how much they loved him, made her own grieving easier.

“It helped us to deal with it together as a whole. In those first few days the weight of the grief is so overwhelming. Sharing Pete’s death with the community in this way helped spread the load. It felt like everyone was carrying a bit, as we slowly came to terms with what had happened.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!