Many writers have tried to encourage conversations about dying, often with the aim of helping us achieve a ‘good death’.

By Jane Mccredie

[A]t dusk some years ago, I walked past an open doorway in the southern Italian village of Paestum. Just inside, a body lay on a table, candles surrounding it, as locals filed in and out, paying their respects.

It struck me at the time how different this was from the general Australian experience, where the end of life is sanitised, hidden and often medicalised to the point of cruelty.

For centuries, our ancestors would have tended their dying relatives, washed their bodies, stood vigil over them in the homes where they lived and died. Many people around the world still do this, of course, but we in the West are more likely to end our days in aged care or, worse, a hospital intensive care unit. We may be subjected to futile, traumatic interventions right up to the moment we take our last breath.

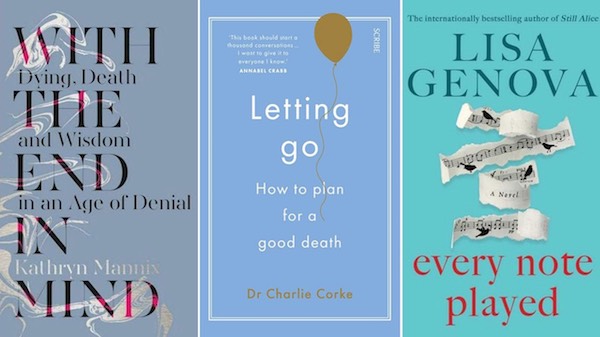

In recent years a number of writers have sought to encourage franker conversations about dying, often with the stated aim of helping us to achieve a “good death”. Notable local books have come from intensive care physician Ken Hillman, general practitioner Leah Kaminsky and science writer Bianca Nogrady. But the reluctance to talk about death remains.

“It has become taboo to mention dying,” writes British palliative care physician Kathryn Mannix in With the End in Mind:

This has been a gradual transition, and since we have lost familiarity with the process, we are now also losing the vocabulary that describes it. Euphemisms like “passed” or “lost’’ have replaced “died” and “dead”. Illness has become a “battle”, and sick people, treatments and outcomes are described in metaphors of warfare. No matter that a life was well-lived, that an individual was contented with their achievements and satisfied by their lifetime’s tally of rich experiences: at the end of their life they will be described as having “lost their battle”, rather than simply having died.

We must reclaim the language of dying, Mannix argues. Clear, unambiguous conversations about what is ahead offer support to the dying person as well as those who will mourn their death. “Pretence and well-intentioned lies” separate the dying from those they love, wasting the limited time they have left. Mannix first discovered the power of straightforward language as a junior doctor when a superior offered to describe to an anxious patient “what dying will be like”. “If he describes what? I heard myself shriek in my head.”

The senior doctor went on to describe in detail the pattern of dying he had observed over years of practice: increasing tiredness, more time spent sleeping, a gradual drift into unconsciousness, followed by changed respiratory rhythms until the breath finally stopped. “No sudden rush of pain at the end. No feeling of fading away. No panic. Just very peaceful … ” he told the patient.

Back in the tearoom, he told the young Dr Mannix this was probably the most helpful gift they could give their patients. “Few have seen a death,” he explained. “Most imagine dying to be agonised and undignified. We can help them to know that we do not see that, and that they need not fear that their families will see something terrible.” Mannix was left amazed that it was possible to be this honest with patients, revising her “ill-conceived beliefs about what people can bear”, beliefs that could have prevented her from having the courage to tell the truth.

Over the decades since that paradigm-shifting experience, she helped countless people of all ages and backgrounds through the final stages of their lives. Their stories are threaded through this moving and informative book. “The process of dying is recognisable,” Mannix writes:

There are clear stages, a predictable sequence of events. In the generations of humanity before dying was hijacked into hospitals, the process was common knowledge and had been seen many times by anyone who lived into their thirties or forties. Most communities relied on local wise women to support patient and family during and after a death, much as they did (and still do) during and after a birth. The art of dying has become a forgotten wisdom, but every deathbed is an opportunity to restore that wisdom to those who will live, to benefit from it as they face other deaths in the future, including their own.

In Letting Go: How to Plan for a Good Death, Australian intensive care specialist Charlie Corke offers practical tools to help people make and communicate decisions about how they would want to be treated at the end of life.

Corke’s professional experience leads him to paint a very different picture of dying from that offered by Mannix. The specialties of intensive and palliative care are in some ways polar opposites: intensive care does everything possible to ward off the inevitable, while palliative care accepts death, seeking to ease the patient’s approach to it.

Corke admires the triumphs of modern medicine and the many achievements of his specialty, but he has also seen how easy it is for medical treatment to go too far. Most of us will die in old age, after a long period of declining health, he writes. One crisis or another will lead to us being taken to hospital by ambulance where, in the absence of clear instructions from us, medical intervention will escalate:

We will spend our last days connected to machines, cared for by strangers, and separated from our family. We will experience significant suffering, discomfort and indignity, receiving increasingly intense treatment that has a diminishing chance of success. Medical technology will dominate our last days and weeks. Our family will be excluded from the bedside, huddled in the waiting room, while “important” things are done to us. Time for connection and comforting, for any sort of intimacy or the opportunity to say goodbyes, will be missed …

The purpose of this book is to help people avoid that outcome. Corke offers clear advice on questions to ask doctors, on writing and sharing a plan, and on appointing a substitute decision-maker to step in if we are unable to express our own views.

Above all, he stresses the importance of clear, unambiguous communication about what we want to happen at the end of life. If there is any doubt about our wishes, maximum intervention will be the result:

Wishes matter, but it can be difficult to get them heard. Wanting to be saved is easy. “To do whatever is required to save” is what everyone wants to do for you, needs to do, and is expected to do. It’s what our medical system is designed to do. It’s the default; it’s what you get. When we want to set limits, it’s more difficult …

All in all, this is a useful how-to manual for everybody who will at some point face death (which is of course all of us).

In Every Note Played, Lisa Genova chooses a different form to explore the end of life.

Over the decade since publication of her first novel, Still Alice, which was filmed with Julianne Moore in the lead role, Genova has mined her background as a neuroscientist for fictional material, producing novels about dementia, autism, traumatic brain injury and Huntington’s disease. In her fifth novel, she turns her attention to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, telling the story of Richard, an acclaimed concert pianist diagnosed with the disease at the height of his career.

ALS is the central, and strongest, character in this book, dwarfing the somewhat one-dimensional human actors and the overneat redemptions they achieve. The merciless progression of the neurodegenerative condition is described with elegant, sometimes gruesome, precision as Richard loses the ability to control first his arms, then legs and, ultimately, everything but his eyes

As in the real-life case studies presented by Corke and Mannix, the approach of death presents Richard and those close to him with appalling dilemmas: How much can we ask of others? How far should we go to preserve life? What does quality of life mean?

Richard’s state of mind as his disease progresses is not helped by the hearty refusal of his brothers to accept the inevitability of his fate. “What are you doing to fight it?” one asks when he sees Richard in a wheelchair. “You gotta stay positive. You should go to the gym, lift some weights and strengthen your leg muscles. If this disease starts stealing your muscle mass, you get ahead of it and build more. You beat it.”

Richard manages a slurred response — “Goo-i-de-a” — while privately wondering at his footballer brother’s incomprehension of his condition:

Is living at any cost winning? ALS isn’t a game of football. This disease doesn’t wear a numbered jersey, lose a star player to injury, or suffer a bad season. It is a faceless enemy, an opponent with no Achilles’ heel and an undefeated record … High tide is coming. The height and grandeur of the sand castle doesn’t matter. The sea is eventually going to rush in, sweeping every single grain of sand away.

Richard’s brothers, like all of us, might have benefited from a share in what Mannix refers to as her “peculiar familiarity with death”:

Strangely, this is not a burden or a sadness, but a lightning of perspective and a joyful spark of hope, a consciousness that everything passes, whether good or bad, and the only time we can really experience is this present, evanescent moment.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!