Amanda Page Brown completed her training to become an end-of-life doula last November and now is trying to secure funding to work full time as a death doula in the area of Vancouver hit hardest by Canada’s overdose crisis

Last fall, Amanda Page Brown visited a friend in the hospital.

“As I was leaving, I saw their roommate laying in bed, skin and bones, and very little life in him,” she told the Straight. In a telephone interview, Brown explained that she recognized the man through her job as a support worker in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

“He was completely alone and no one knew he was there, dying,” she continued. “I asked him if it would be okay if I visited again. He said yes.”

Brown sat with the man once more before he passed away a few days later. “I realized I was the only person who knew,” she said. “I was it.”

The experience affected Brown deeply. “He taught me much over those three final days,” she said. “He taught me the path I’m meant to walk.”

Brown learned that she wanted to help people in the Downtown Eastside make the transition from life to death. Especially those residents who might not have anyone else to be with them during that time. She began researching how she might be able to do that, and found a certificate course at Douglas College.

“End-of-Life Doulas are advocates for their clients and complement the work of the medical community and hospice-palliative care workers and volunteers,” the program’s website reads. “End-of-Life Doulas assist clients in creating and carrying out their health-care treatment decisions, as well as providing support to clients and their family and friends.”

Brown completed her training to become an end-of-life doula (also known as a death doula) last November. Now she’s trying to secure funding to work full time as a death doula in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

Brown said that her plan is to collect support via her Facebook page and an accompanying fundraiser, but hopefully not for more than one year. Then, with a little experience under her belt (plus the previous seven years she’s spent employed in the Downtown Eastside), she’s hoping she can secure a staff position or reliable and sustainable funding from one or several of the many government agencies, private organizations, and nonprofits that operate in the neighbourhood.

“As a doula, you can walk in as a trusted friend. That’s what is needed here,” Brown said. “I want to be able to offer things like bedside vigils. If somebody is going to be taken off of life…and if that person doesn’t want to die alone, then somebody should be sitting with them.”

There are typical scenarios where it’s easy to understand why a death doula might be needed. For example, an elderly Downtown Eastside hotel tenant with an alcohol problem who doesn’t have any family. But Brown described other situations where it might be less obvious how someone could benefit from the presence of a death doula.

“I’ve asked drug users who have had quite a few overdoses, ‘Has anybody ever asked you if you are trying to kill yourself?'” she recounted. Brown said that with folks in that type of situation, she could befriend them and, once a bond is established, offer to help them draft an advance-care plan.

“Hey, I hear that your overdosing a lot,” Brown explained she could say to them. “Does anybody know your wishes in case something does happen to you?…Because we can do this on a legal piece of paper. Why don’t we do this?”

Brown added that these types of conversations can have unintended benefits.

“That might actually open up another conversation about maybe treatment or detox,” she said. “Maybe, maybe not. But it might be another way to open another very important conversation down here.”

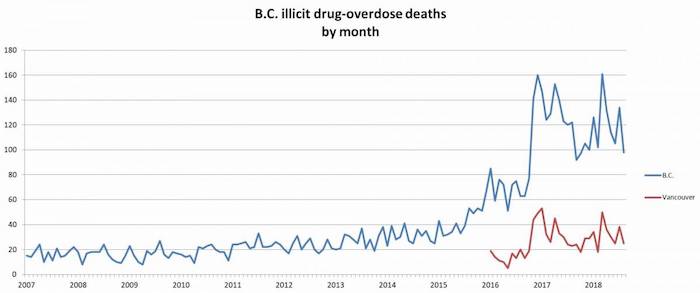

There were 367 illicit-drug overdose deaths in Vancouver last year, up from 235 in 2016 and 138 the year before that. For every fatal overdose that occurs in the city, there are many more that are reversed.

Coco Culbertson is a senior programs manager with PHS Community Services Society (PHS), a nonprofit that manages more than a dozen supportive-housing buildings in Vancouver. She also happens to have the same end-of-life doula certificate that Brown has.

“There are volunteer networks that provide this service for free, but maybe not necessarily for the population that we support,” Culbertson told the Straight. “There are so many people in the Downtown Eastside who are living with a chronic illness and comorbidity and who become palliative or require some level of hospice. And there are very limited resources for those folks.

“Having someone who has the expertise and the empathy—professionalized empathy—to sit with them as they live out the last few days, weeks, or months of their life, would be an incredibly meaningful thing,” she said.

Culbertson noted that PHS staff often spend time with tenants who have been transferred to a hospital and are nearing the end of their life. But everyone is spread thin, especially since the dangerous synthetic-opioid fentanyl arrived and overdoses skyrocketed, she added.

“Someone who is able to provide more support for people who don’t have a family…that would be an incredibly important thing,” Culbertson said. ” I think it is just as important to offer dignity and humanity in death as it is in life.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!