— A broad-ranging analysis asks whether we can achieve a kind of immortality by documenting our lives and deaths online.

Through virtual reality, people can interact with avatars of loved ones.

The Digital Departed: How We Face Death, Commemorate Life, and Chase Virtual Immortality Timothy Recuber NYU Press (2023)

Many of us will have turned to the Internet to grieve and remember the dead — by posting messages on the Facebook walls of departed friends, for instance. Yet, we should give more thought to how the dead and dying themselves exert agency over their online presence, argues US sociologist Timothy Recuber in The Digital Departed.

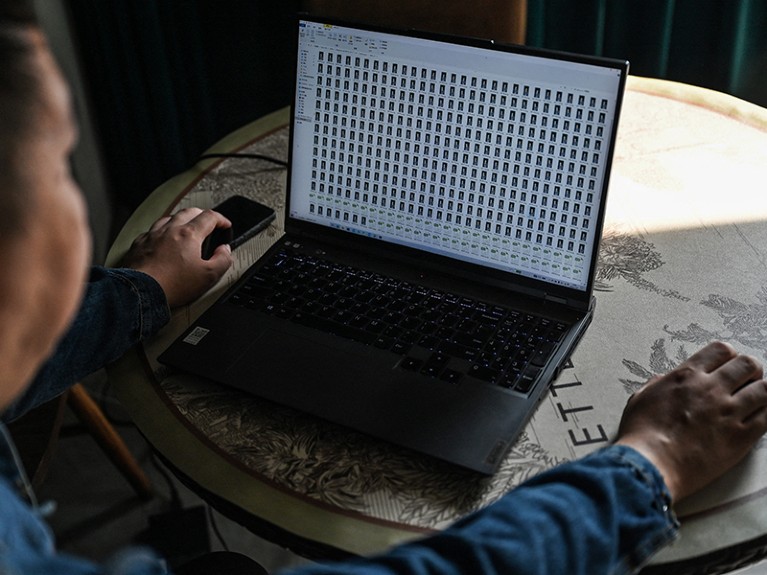

In his expansive scholarly analysis, Recuber examines more than 2,000 digital texts, from blog posts by those who are terminally ill to online suicide notes and pre-prepared messages designed to be e-mailed to loved ones after someone has died. As he notes, “the digital data in this book are sad, to be sure, and they have often brought me to tears as I collected and analyzed them”. Yet, they are well worth delving into.

Recuber brings a fresh lens to studies of death culture by focusing on the feelings and intentions of the people who are dying, rather than those of the mourners. For example, he finds that a person’s sense of self can be altered through blogging about their illness. Writing freely helps people to come to terms with their deaths by making their suffering “legible and understandable”. Reflections on family and friends also reveal a sense of self-transformation. Indeed, many bloggers “attested to the positive value of the experience of a terminal illness, for the way it brought them closer to loved ones and especially for the wisdom it generated.”

This theme of self-transformation, which Recuber refers to as ‘digital reenchantment’, continues throughout the book. This terminology relates to the work of German sociologist Max Weber, who, at the turn of the twentieth century, argued that humans’ increasing ability to understand the world through science was robbing life of magic and mystery — a process he called disenchantment. When the dead seem to be resurrected through digital media, Recuber argues, they regain that mystery.

Recuber explores how X (formerly Twitter) hashtags can act as a form of collective online rememberance. He focuses on photos and stories shared in posts that use two hashtags, sparked by violent deaths of Black people in the United States: #IfIDieInPoliceCustody, in response to Sandra Bland’s death in prison in Waller County, Texas, in July 2015, and #IfTheyGunnedMeDown, which remembers Michael Brown, who was shot by police in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014. The “thousands of individual micro-narratives” posted in these threads, Recuber writes, amount to a “collectively composed story affirming the value of all Black lives and legacies”. They are memorials for the lives that have already been lost and for those that might be in future.

The author considers the perspectives of the individuals whose deaths inspired each hashtag. For example, 28-year-old Bland was imprisoned after being arrested for a driving offence. Friends and family questioned the police’s assertion that Bland had committed suicide, and #IfIDieInPoliceCustody was tweeted 16,500 times in its first week, as the result of the online attention that the case gained. What would Bland and Brown think of this coverage, Recuber asks? They might have been proud of this legacy, but they had no say in it. In a sense they are “doubly victimized”, he suggests, losing not only their lives but also “the agency to define themselves and the ways they’d like to be remembered”.

In the book’s most intriguing section, Recuber turns to transhumanism — the idea that, some time in the future, advanced technologies yet to be imagined could enable digital records of the human mind to be uploaded to the Internet. A person’s consciousness could then ‘live’ online forever.

Recuber interviews four men who lead companies that are helping people to preserve digital aspects of themselves or that are otherwise concerned with transhumanism. Bruce Duncan runs the Lifenaut project, part of the non-profit Terasem Movement Foundation, based in Bristol, Vermont, which allows users to create a digital archive of their reflections, photos and genetic code for future researchers to study. Eric Klien is the president and founder of the Lifeboat Foundation, a non-governmental organization based in Reno, Nevada, which is devoted to overcoming catastrophic and existential risks to humans, including from misuse of technologies. Robert McIntyre is the chief executive of Nectome, based in San Francisco, California, which works on techniques for embalming brains for future information retrieval. And Randal Koene is the chief scientific officer of the Carboncopies Foundation, based in San Francisco, a research organization that works on whole-brain emulation — a “neuroprosthetic system that is able to serve the same function as the brain”.

According to Recuber, none could give a clear explanation for how mind uploading would work. That’s not surprising — neuroscientists are divided on whether it is even possible. But each interviewee had faith that it would become a possibility. Koene wonders whether uploaded minds might find a home in some kind of robotic body. Duncan and McIntyre imagine a disembodied human consciousness able to travel through space and visit other planets or stars.

Yet, Recuber was troubled to find that these men said very little about the social and ethical questions raised by mind uploading. Building a ‘superior’ type of human has a “whiff of eugenics” about it, he writes. The whole process would be expensive, perhaps creating a future division in social classes, with only the rich able to afford it. Duncan and Koene pointed out that this might not be true in the future — the prices of technologies, such as smartphones and data-storage units, tend to fall quite quickly.

Recuber does find people raising ethical concerns on the online discussion platform Reddit, where he examined more than 900 posts about transhumanism. One user was appalled that “the richest and most comfortable people in history spent their money and resources trying to live forever on the backs of their descendants”. But philosophical debates are much more popular, such as whether the uploaded disembodied mind would be equivalent to or superior to one’s own.

Transhumanism, Recuber notes, is working towards a very different type of online legacy from those discussed elsewhere in his book; it is focused not on strengthening ties with humanity but on cutting them. This idea of moving beyond mortal biological limits — gaining immortality through science and technology — is an old dream in a new guise. For religious people, the immortal substance is the soul; for transhumanists, it is the mind.

It is in these critiques of transhumanism that Recuber is at his sociological best. His astute comments exemplify a second theme of The Digital Departed — that inequalities that persist in the physical world are mirrored in peoples’ online lives. He cautions the public about narratives that promote technological progress as necessarily good. Despite the rhetoric of liberation through technological progress, we all must remain wary. There are no guarantees that mind uploading will be properly regulated, or benefit those in need. Mortal problems such as food and water shortages and human violence, as well as the lack of housing and health care, have greater priority in my view.

It is a shame, however, that the book ignores feminist perspectives on transhumanism. These contend that ideas of the soul or mind in philosophy have historically operated as a gender hierarchy — men and the masculine are considered primordial, whereas women and the feminine are treated as secondary, linked to the body and the mortal realm. Transhumanism will not benefit women or gender-diverse people unless it engages with its own inherited systems of thought and narrative.

Nonetheless, The Digital Departed is a valuable book that presents many moving stories about the way that our digital life foreshadows our biological departure. The author’s engagement with classical and modern sociological theory will be appreciated by scholars and appeal to readers of all stripes.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!