By David Wallace-Wells

Since it was first introduced by the economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton in 2015, the phrase “deaths of despair” has become a sort of spiritual skeleton key that promised to unlock the whole tragic story of a new American underclass.

Beginning around the turn of the millennium, Case and Deaton showed, deaths from suicide, opioid overdose and alcohol-related liver disease among less educated, white, middle-aged people began to grow in a pattern that seemed to demonstrate how the country’s white working class was being — or at least feeling — left behind. Last month, the economists presented their updated data with a new paper showing a growing divergence in life expectancy between those with college degrees and those without.

But over the past few years, the “deaths of despair” story has come to seem thinner to many of those reading the literature most closely. And in response to the new findings, pointed critiques were published by Dylan Matthews in Vox and by Matthew Yglesias in Slow Boring, arguing that the deaths of despair narrative had been overhyped, creating a just-so story about postindustrial decline that had seemed too good to scrutinize.

Eight years on, the central claim from Case and Deaton holds up relatively well: Deaths by suicide, overdose and liver disease have been on the rise among the white working class and the middle class. But so have gun deaths across the country, deaths among the young and suicides, which puts the data on white middle-aged men and women in a different light. Among other questions about that data, it turns out that deaths of despair increased pretty uniformly across all demographic groups and that the rise in such deaths among white middle-aged people was, while real and concerning, not all that exceptional.

What does that imply, though? In their critiques, both Yglesias and Matthews argue that the data tells a narrower story than Case and Deaton do — and that rather than invoking national malaise we should focus on the role of opioids among the country’s worst off in the first case, or high school dropouts and heart disease in the second.

But it seems to me that the opposite is true: The American mortality crisis is much larger than deaths of despair, in fact too broad and diffuse to be stuffed into one demographic box or characterized as a failure of one policy area. You can see it almost anywhere you care to look and any way you slice the data.

Unless they’re in the top 1 percent, Americans are dying at higher rates than their British counterparts, and if you’re part of the bottom half of income earners, simply being American can cut as much as five years off your life expectancy. At every age below 80, Americans are dying more often than people in their peer nations: Infant mortality is up to three times as high as it is in comparison countries; one in 25 kindergartners can’t expect to see 40, a rate nearly four times as high as in other countries; and Americans between 15 and 24 are twice as likely to die as those in France, Germany, Japan and other wealthy nations. For every ethnic group but Asian Americans, prepandemic mortality rates in the United States were higher than those of economic peer countries: In 2019, Black Americans were 3.8 times as likely to die as the residents of other wealthy countries, white Americans were 2.5 times as likely to die, and Hispanic Americans 1.8 times as likely to die. Americans with college degrees do substantially better than those without, but that second group represents almost two-thirds of the country. And while mortality rates show a clear geographic divergence, with life expectancy gaps as large as 20 years between the country’s richest and poorest places, just a fraction of American counties even reach the European Union average.

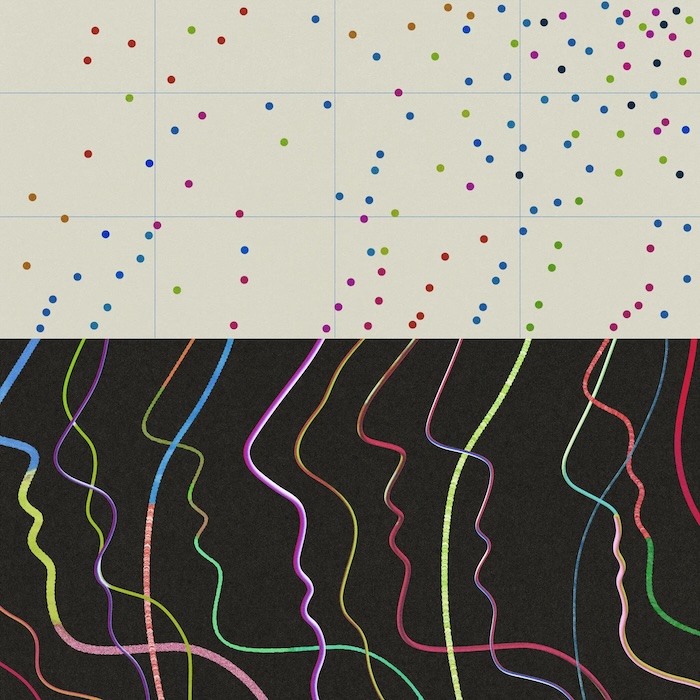

When looking at American trend lines alone, anomalies like overdose spikes or mortality increases among high-school dropouts can jump out, and the divergence between, say, those with bachelor’s degrees and those without is quite striking. But in comparing the overall health of Americans to those in other wealthy countries, almost everyone looks to be suffering, and even those remarkable anomalies turn out to be quite small, contributing only somewhat trivially to the widening gap between how many Americans are dying each year and how many of our peers elsewhere are.

Overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, for instance, have grown from less than 10,000 in 2015 to 70,000 in 2021. Add heroin and other overdoses and the total grows to more than 100,000 — a public health horror story, and a much graver problem than in any of our peer countries. But that barely explains a fraction of the exceptional American mortality pattern identified by the researchers Jacob Bor and Andrew Stokes, who found that a million more Americans died each year than would have if the country’s overall mortality rates matched those of peer countries in Europe.

Those million extra deaths exceed even the nearly 700,000 who die each year from cardiovascular disease, the country’s biggest killer. But of course many residents of other rich countries die from it, too. And though, as Matthews emphasizes, American progress against heart disease has stalled in recent years, the gap between our cardiovascular mortality and those of our peers turns out to be relatively small, accounting for just another fraction of Bor and Stokes’s “missing Americans.” Which tells you something about how large that number of extra deaths really is: If American mortality rates simply matched those of peers overall, the country’s total number of deaths would have fallen 22 percent on the eve of the pandemic in 2019. In 2021, the researchers found, extra mortality accounted for nearly one in every three American deaths.

“The United States is failing at a fundamental mission — keeping people alive,” The Washington Post recently concluded, in a remarkable series on the country’s mortality crisis. “This erosion in life spans is deeper and broader than widely recognized, afflicting a far-reaching swath of the United States.” In a quarter of American counties, The Post found, death rates among working-age adults are not just failing to improve but are also higher than they were 40 years ago. “The trail of death is so prevalent that a person could go from Virginia to Louisiana, and then up to Kansas, by traveling entirely within counties where death rates are higher than they were when Jimmy Carter was president.” If death rates just among the country’s 55-to-69-year-olds improved to match the rates of peer countries, The Post calculated, 200,000 fewer of them would have died in 2019. That is more than the number of them who died of Covid in 2020.

There are a few things that Americans do as well or better than other countries (cancer treatment, where outcomes have been steadily improving now for decades, and keeping old people alive), so chances that a 75-year-old makes it to 90 or 100 are about the same as in other wealthy countries — though that stat is somewhat distorted by the fact that many fewer Americans make it to 60 in the first place, with those who do likelier in better health.

But by almost every other measure the United States is lagging its peers, often catastrophically. The rate of homicides involving a firearm are 22 times higher in the United States as in the European Union, for instance, a worsening trend that has given rise to research suggesting that the country’s mortality crisis is primarily about gun violence. Another set of researchers emphasize exceptional mortality rates among the young, with rates of death among American children growing more than 15 percent between just 2019 and 2021, with little of that increase attributable to Covid. Americans also die much more often in car crashes, workplace accidents and fires. Our maternal mortality rate is more than three times as high as that of other wealthy countries, and our newborns have the highest infant mortality rate in the rich world. We are almost twice as likely to suffer from obesity as are our counterparts in countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the downstream consequences — from hypertension to heart disease and stroke — mean that obesity could explain more than 40 percent of the U.S. life expectancy shortfall for women, and over 60 percent for men. The life expectancy among America’s poorest men may be 20 years shorter than that of their counterparts in the Netherlands and Sweden. Overall, among 18 high-income countries, America’s life expectancy ranks dead last.

It’s not quite right to call all this simply “despair,” even if social anomie plays a role. Doing so places too much weight on the suffering of individuals and not enough on what epidemiologists call the social and environmental determinants of health: community support, education and, perhaps most important, health care access. (Since 2015, Case and Deaton have acknowledged these factors; their 2020 book on the subject emphasizes health care inequalities, and Deaton’s new book “Economics in America” focuses squarely on inequality.)

But the bigger problem seems to me to be that talking narrowly about despair localizes the American mortality dysfunction in a small demographic, when almost the entire country is dying at alarming rates. The burden does not fall equally, and the disparities matter. But looking globally, our mortality crisis appears, effectively, national.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!