[E]verywhere around me even in modern day 2017, it seems like as a single person I’m confronted with the same message

“Here’s how to find the real love of your life!” Some old guy in a tuxedo exclaims at me from an eHarmony commercial.

“You’re totally like Carrie Bradshaw,” my friends say over drinks when I talk about my job and how I’ve gone out on dates with a few different guys this month. “Now you just need your Big.”

We just don’t want to be alone the countless submissions I read every day proclaim in their honest, heartsick words and in their desperate and painfully lonely headlines.

I’m afraid of a lot of things. I hate driving and am always convinced a semi-truck will run me off of the interstate and send me plummeting to my death. I love paddle boarding but have a weird anxiety about going too far out where the water is a certain level of deep because realistically – who knows what’s down there. The idea of my dog dying when I’m not home makes my eyes start watering just typing it out.

I’m afraid of a lot of things, but dying alone isn’t one of them.

One of my best friends told me a story about how her dad always used to tell her that no matter what, she had to like herself because she was the only person who ever really would ALWAYS be there. And that’s the truth. Some people would say that’s cynical and glass-half-empty, but I say it’s simply honest.

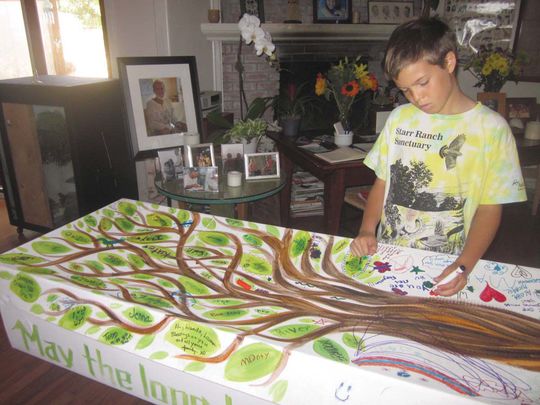

Think about it. Even if you do fall in love, madly in love, the kind of love that people write sonnets about and songs about and paint all over a building as a mural – eventually you’re going to die. And even if that person has been there day in and day out, holding your hand and kissing you despite your morning breath, the only person who you’ll have in those final moments is yourself. All you really have, is you.

So you’d better like you.

I think what we’re really not saying when we say we’re afraid of dying alone is that we’re really not afraid of the alone part, we’re afraid of only having ourselves to hold onto. We’re afraid that somehow, we won’t measure up. We won’t be enough. That somehow, we’re an incomplete puzzle without some else’s edge pieces.

When we say we’re afraid of dying alone we’re really saying we’re afraid that we’ll never be happy with just ourselves, and that we need someone else to dictate that level of completeness to our lives.

But you know what? The little secret that no one wants you to figure out – that the man in the suit hopes you never realize, and anyone writing a “Here Is How You Find The Love Of Your Life And Never Eat Alone Again” book hopes you don’t come to terms with?

A fear of dying alone is really just a fear of not living a life you love. A life you’re excited about. A life that makes you feel enough.

And they never want you to know that crushing that fear is simple. All you have to do is refuse to let it in.

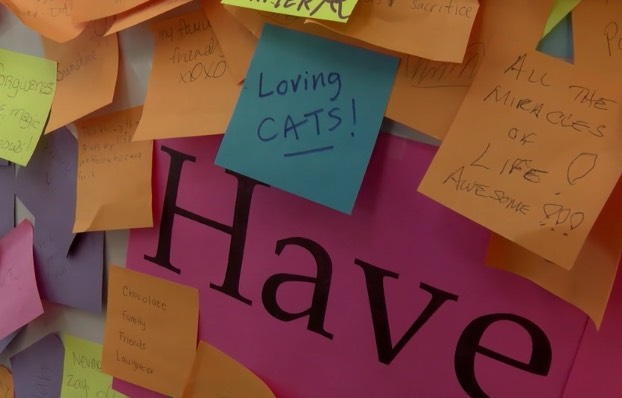

So when you’re worried about eating alone, grab a book that swallows you with its characters and its story and go treat yourself to some Alfredo and wine and give it no second thoughts. If you’re scared of your life being empty, make friends with people who never cease to make you smile and challenge you in the ways you need. Fill your days with a job you love, with travels that blow your mind, and create a life that bears no need for another person other than yourself.

That way, if someone comes alone, they’re just and enhancement, not a requirement.

Your fear of dying alone isn’t sign of being an incomplete or unlovable person — it’s simply a sign that you just need to love yourself enough to stop being so afraid.

Complete Article HERE!