‘I’ve got a busload of people up here in my head’

J.P. Trottier was with the Ottawa Paramedic Service for 36 years – 21 as a frontline paramedic and 15 as public information officer. He retired in January 2017.

“I don’t know how many deaths I’ve seen, but it’s in the hundreds. I remember one shift doing three vital-signs-absent calls in a row. That was a busy eight hours.

“You just never know where you’re going to be in five minutes. Are you going to be in the middle of a crime scene? Are you going to be in somebody’s living room, somebody with abdominal pain? Somebody having a heart attack?

“Sometimes, it’s just the daily grind. It can be very humdrum, and then all of a sudden your next shift will be just crazy. You’ll do a shooting, you’ll do an elderly gentleman who’s collapsed at home and his vital signs are absent, you’ll do a childbirth call … you’ll do a whole bunch of different things.”

“You have some really horrible moments in the job, and you have some absolutely spectacular moments. Paramedics have what they call the holy-shit call. They take a look at the person and they know they’re in trouble — that that person is in deep trouble and probably minutes from dying. We call that the holy-shit call. It’s like, get to work. And you can tell after a little bit of experience — you walk into a room and look at somebody. And then it becomes a bit mechanical; your training kicks in and you don’t really think about it. But when you see them like that and 10 minutes later you’ve given your medication and taken your vital signs, or your partner’s taking the vital signs and you’ve slapped the oxygen on them or maybe put in an IV and put the medication in when all the vital signs are OK and off you go. And 10 minutes later when they’re looking much better, it’s an amazing thing to see. It’s absolutely beautiful. It’s absolutely the best part of the job.”

•

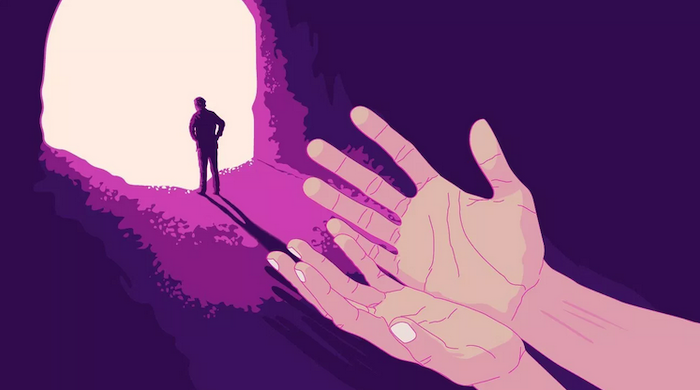

“You don’t forget many of them. The difficult ones you don’t forget. I tell people that I’ve got a busload of people up here in my head, waiting to step out. It’s not being haunted; it’s just that you will never be able to forget that eight-year-old boy who played chicken with a train and lost. You’ll never be able to forget that. If anybody were to come to me and say, ‘Oh, I can handle it … ” Yeah, OK, maybe you can handle it differently than I can, but there’s no way you’re going to be able to forget that. The young boy who comes home from school for lunch and finds his mother dead upstairs because she put a shotgun in her mouth. You’ll never be able to forget that. Never. But they don’t haunt me.

“Very early in my career I had one of those horrible calls – it was a young girl, six or seven years old, crossing the street and was struck by a car. She died en route, and every time I drive by there, it’s like, ‘This is where it happened.’ And it’s no more than that. But they’re with you.”

•

“There’s that horrible side where you can’t help … they’re in a car crash, pinned, and the paramedics are trying to put the IV in and they’re doing a whole bunch of different things, and you’re waiting and waiting, and the blood pressure is coming down and down and down, and you can’t stem the bleeding because you can’t access where the injury is.

“So yeah, sometimes you can’t resuscitate them, and that’s the moment that you turn your attention to the family. They’re not the patients, you’re not there specifically for them or because of them, but all paramedics will do this; they will turn their attention to the family.

“I used to do presentations for career days at high schools, and they would ask what’s the most important thing about your character that would make you a good paramedic, and I would say two things. The first was that you really have to be a caring person, because that’s what you do. That’s your job, you’re caring for people — their emotional needs, their physical needs. And the second part is good communications skills. You must have good communications skills because of instances like this, where a family member has passed away and you need to inform them. And don’t use any jargon, don’t use any of that nonsense. ‘I’m sorry he passed away. We couldn’t do anything.’ And you don’t give them a lot of info, because they’ll forget most of it after you tell them.

“We have to be careful what we tell them, because they will remember that moment, forever. It really demands respect, and I don’t care if they’re gang members or whatever the case may be. We don’t care; it’s a patient and they have friends or family, and there’s a mother or father somewhere, maybe, or children, grandchildren or great-grandchildren, and all of them will be affected by this.”

•

“I would often turn my attention to people’s rooms to give me an idea of the life they led. The older generation especially will have a lot of photographs on their dressers or in the bedroom. Even if I don’t know these people, it kind of puts you there. Look at the clothes they’re wearing. Look at the cars they were driving. It gives you a bit of a glance at their lives. There are pictures of their children and grandchildren. It kind of gives you a quick bio of them.

“The ones that really stand out for me are ones where someone’s standing next to a Spitfire, because you know they served. Did he fly planes? Was he in the war? Was he a mechanic? You can sometimes ask the family a little bit about them — you have to tread carefully there, because they may not take it very well. But in some instances I was able to ask the family. ‘Oh, he served?’ — because there’s a picture of him. ‘Yes, and he went to this battle and that battle,’ and of course they’re proud of that. And sometimes I take a minute to thank them for their service to their country. Sometimes you’ll see their medals on the wall, and you can talk about that a little bit.

“It can be fascinating. You don’t know about this person or the life they led, if they discovered a cure for something. You just never know.”

•

“Has my view of death changed over the years? Yes. I think just because of the sheer number of calls that we do with death and near-death … a patient you were able to get back from the grip of death that they were in. The shootings, the stabbings, the crib deaths — Sudden Infant Death Syndrome — for sure, gave me a better understanding of death. You’re more aware of death and what it means and why it happens, a little bit — we can never know why, really. But it gives you a better appreciation of it, and thus a better understanding of it.”

“You see a lot of circumstances. The suicides are sad. And you also see the murder-suicides, and those are weird. There was one I did where this man had custody of his child during the weekend, and he decided on Sunday night that the child was not going back home to his mother, and threw him off the balcony and then jumped himself.

“So you get to the scene and you’ve got this to deal with. And you only know the circumstances after the fact, but you have a damn good clue that at three o’clock in the morning, when the OC Transpo driver found him when going out to his shift, that the kid, maybe two or three years old, didn’t wake up fully dressed at three o’clock in the morning to jump off of the balcony. So now you’ve got that anger issue. You want to kill yourself? That’s somewhat understandable. But to take an innocent child away from his mother and his life? It’s just … it’s weird. There’s this brain storm happening there in your head, in my head, that’s very difficult to deal with and make sense of. So those are very difficult to do.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!