How the pandemic is changing our understanding of mortality.

By BJ Miller

This year has awakened us to the fact that we die. We’ve always known it to be true in a technical sense, but a pandemic demands that we internalize this understanding. It’s one thing to acknowledge the deaths of others, and another to accept our own. It’s not just emotionally taxing; it is difficult even to conceive. To do this means to imagine it, reckon with it and, most important, personalize it. Your life. Your death.

Covid-19’s daily death and hospitalization tallies read like ticker tape or the weather report. This week, the death toll passed 300,000 in the United States. Worldwide, it’s more than 1.6 million. The cumulative effect is shock fatigue or numbness, but instead of turning away, we need to fold death into our lives. We really have only two choices: to share life with death or to be robbed by death.

Fight, flight or freeze. This is how we animals are wired to respond to anything that threatens our existence. We haven’t evolved — morally or socially — to deal with a health care system with technological powers that verge on godly. Dying is no longer so intuitive as it once was, nor is death necessarily the great equalizer. Modern medicine can subvert nature’s course in many ways, at least for a while. But you have to have access to health care for health care to work. And eventually, whether because of this virus or something else, whether you’re young or old, rich or poor, death still comes.

What is death? I’ve thought a lot about the question, though it took me many years of practicing medicine even to realize that I needed to ask it. Like almost anyone, I figured death was a simple fact, a singular event. A noun. Obnoxious, but clearer in its borders than just about anything else. The End. In fact, no matter how many times I’ve sidled up to it, or how many words I’ve tried on, I still can’t say what it is.

If we strip away the poetry and appliqué our culture uses to try to make sense of death — all the sanctity and style we impose on the wild, holy trip of a life that begins, rises and falls apart — we are left with a husk of a body. No pulse, no brain waves, no inspiration, no explanation. Death is defined by what it lacks.

According to the Uniform Determination of Death Act of 1981 (model legislation endorsed by both the American Medical Association and the American Bar Association, meant to guide state laws on the question of death), you are dead if you have sustained “either irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions” or “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem” — in other words, no heartbeat and no breathing, which is obvious enough, or no brain function, which requires an electroencephalogram.

These are the words we use to describe one of the most profound events in human experience. Most states have adopted them as the legal definition of death. They may be uninspired, and they surely are incomplete. Either way, a doctor or nurse needs to pronounce you dead for it to be official. Until then, you are legally alive.

If we stay focused on the body, the most concrete thing about us, it becomes difficult to say whether death exists at all.

From the time you are born, your body is turning over. Cells are dying and growing all day, every day. The life span of your red blood cells, for example, is about 115 days. At your healthiest, living is a process of dying. A vital tension holds you together until the truce is broken.

But your death is not the end of your body. The chemical bonds that held you together at the molecular level continue to break in the minutes and months after you die. Tissues oxidize and decay, like a banana ripening. The energy that once animated the body doesn’t stop: It transforms. Decay from one angle, growth from another.

Opinion Today: Get expert analysis of the news and a guide to the big ideas shaping the world.

Unfettered, the decay process continues until all that was your body becomes something else, living on in others — in the grass and trees that grow from where you might come to rest, and from the critters who eat there. Your very genes, little packets of stuff, will live indefinitely as long as they found someone new to host them. Even after interment or cremation, your atoms remain intact and scatter to become other things, just as they pre-existed you and became you.

For revelation of the mysteries of an afterlife, or of the forces that kicked off this wondrous circus in the first place, we might look to religion. What is described above is plainly observable science. Yet science doesn’t do the question justice. It won’t tell us why, or what’s behind its laws. The body houses more than we can express; you are more than your body. Becoming a blade of grass is a sweetness that doesn’t compensate for all the heartache death connotes.

Of course, we’re sad and afraid of losing ourselves and people we love, but for many of us a fear of death as the Great Unknown has been overtaken by our fears of what we know — or think we know — about dying.

Nowadays, being dead sounds like a lullaby compared with the process of dying. Given a steadily awful diet of stories about breathing machines and already-disenfranchised people dying alone, we’re told to imagine the worst, before cutting to commercial. Our choices seem to be either to picture a kind of hell — that could be mom or me, breathless and alone — or to distance ourselves from the people living those stories, not just in body but in every way, to de-identify with our fellow human beings.

But this is how we make hard things harder. Maybe our fear of death has more to do with our perceptions of reality than with reality itself, and that is good news. Even if we can’t change what we’re looking at, we can change how we look at it.

We do have fuller ways of knowing. Who doubts that imagination and intuition and love hold power and capacity beyond what language can describe? You are a person with consciousness and emotions and ties. You live on in those you’ve touched, in hearts and minds. You affect people. Just remember those who’ve died before you. There’s your immortality. There, in you, they live. Maybe this force wanes over time, but it is never nothing.

And then there’s consciousness — spirit, if you like — and of this, who can say? You may have your own answer to this question, but we do not get to fall back on empiricism. Whatever this mystery is, it blurs all the lines that seem at first glance to separate death from life. And if death isn’t so concrete, or separate, maybe it isn’t so frightening.

The pandemic is a personal and global disaster, but it is also a moment to look at the big picture of life. Earlier this week I had a patient lean into her computer’s camera and whisper to me that she appreciates what the pandemic is doing for her: She has been living through the final stages of cancer for a while, only now her friends are more able to relate to her uncertainties, and that empathy is a balm. I’ve heard many, in hushed tones, say that these times are shaking them into clarity. That clarity may show up as unmitigated sorrow or discomfort, but that is honest and real, and it is itself a powerful sign of life.

So, again, what is death? Talking about and around it may be the best we can do, and doing so out loud is finally welcome. Facts alone won’t get you there. We’re always left with the next biggest question, one that is answerable and more useful anyway: What is death to you? When do you know you’re done? What are you living for in the meantime?

For some of us, death is reached when all other loved ones have perished, or when we can no longer think straight, or go to the bathroom by ourselves, or have some kind of sex; when we can no longer read a book, or eat pizza; when our body can no longer live without the assistance of a machine; when there is absolutely nothing left to try. Maybe the most useful answer I ever came across was the brilliant professor who instructed his daughter that death was what happened when he could no longer take in a Red Sox game.

If I had to answer the question today I would say that, for me, death is when I can no longer engage with the world around me. When I can no longer take anything in and, therefore, can no longer connect. At times, social distancing has me wondering if I’m there already, but that’s just me missing touching the people I care about. There are still ways to connect with others, including the bittersweet act of missing them. And besides, I get to touch the planet all day long.

These are helpful questions to consider as you weigh serious medical treatment options, or any time you have to choose whether to mobilize your finite energy to push, or use it to let go. Our answers may be different, but they are always actionable; they are ends around which we and our inner circles and our doctors can make critical decisions.

They also have a way of illuminating character. They are an expression of self, the self who will one day do the dying and so gets to say. What is it you hold dear? Who are you, or who do you wish to be? You can see how death is better framed by what you care about than by the absence of a pulse or a brain wave.

Beyond fear and isolation, maybe this is what the pandemic holds for us: the understanding that living in the face of death can set off a cascade of realization and appreciation. Death is the force that shows you what you love and urges you to revel in that love while the clock ticks. Reveling in love is one sure way to see through and beyond yourself to the wider world, where immortality lives. A pretty brilliant system, really, showing you who you are (limited) and all that you’re a part of (vast). As a connecting force, love makes a person much more resistant to obliteration.

You might have to loosen your need to know what lies ahead. Rather than spend so much energy keeping pain at bay, you might want to suspend your judgment and let your body do what a body does. If the past, present and future come together, as we sense they must, then death is a process of becoming.

So, once more, what is death? If you’re reading this, you still have time to respond. Since there’s no known right answer, you can’t get it wrong. You can even make your life the answer to the question.

BJ Miller is a hospice and palliative medicine physician, author of “A Beginner’s Guide to the End: Practical Advice for Living Life and Facing Death,” and founder of Mettle Heath, which provides consultations for patients and caregivers navigating serious illness.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Rethinking Black Friday to include end-of-life conversations

By L.S. Dugdale

With more than 250,000 Americans killed by Covid-19, it’s time to think about reimagining Black Friday.

Police officers in Philadelphia gave the Friday after Thanksgiving its dark name in 1966 as zealous shoppers mobbed streets and sidewalks. But it quickly came to mean a day when business owners could expect their accounts to be in the black, as opposed to in the red.

If Black Friday celebrates American consumers spending in order to live well, we could also adopt it as a day to consider what it means to die well. As the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus ostensibly put it, “The art of living well and the art of dying well are one.”

As a physician, I’ve met countless patients who were ill-prepared for death. The “trajectories of decline” described by geriatrician Joann Lynn make it easy not to prepare. Some people live for years with chronic illnesses but feel no need to ponder their mortality. Hospital tune-ups enable them to live seemingly forever. Others enjoy relative health until being caught off guard by a deadly illness. Still others live good long lives only to succumb to dementia, which robs them of their ability to plan.

We are habituated to living with hope for intervention or cure. To accept the impossibility of treatment is to admit defeat, which most people are loathe to do.

How and where we die underscores how unprepared we are. Most Americans have never had end-of-life conversations or formalized their wishes for medical treatments at the end of life. Despite existing in some form since the 1970s, only 37% of Americans report having formalized their wishes through an advance directive. What’s more, most Americans say they want to die at home, yet roughly 60 percent die in hospitals, nursing homes, and hospices. There’s no question that institutional care can be a lifesaver for families not equipped to care for their loved ones at home.

If we are to realize the ideal of death at home surrounded by family, we’ve got work to do. Making a home death possible requires difficult decisions — in end-of-life conversations with family members and health care professionals — about which treatments and hospitalizations to forgo, whether homes can accommodate hospital beds, and who will do the hard work of caring for the dying.

That’s where taking a new approach to Black Friday comes in. On that day, families could pivot from giving thanks to giving thought to ending well. A simple prompt for starting end-of-life conversations might be, “Mom, Dad, if you become so sick that you can’t speak for yourself, who would you want to make medical decisions on your behalf?” And the natural follow-up would be, “Help me know how to advocate for you. Let’s talk about the benefits and burdens of particular medical interventions.” Conversation can then move to broader community-based issues such as funeral, burial, and religious or existential concerns.

It’s not the easiest conversation to have, but the payoff can be worth the effort. And since Black Friday comes every year, it’s a discussion that can build on itself over time.

A reimagined Black Friday could help Americans formalize their wishes for care at the end of life. Advance care planning documents allow people to identify health care proxies to make medical decisions if they lose decision-making capacity. Living wills specify an individual’s choice to have — or not have — cardiac resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, and other invasive procedures.

To be fair, there are good reasons why some people don’t want to prepare for death. Many of my patients fear that talk of death might “jinx” them. Some are reluctant to put their wishes in writing because they worry that doctors will give up on them. Others are concerned they’ll change their minds down the road but be too sick to say so. These concerns are real, but the potential exists for much greater harm by ignoring finitude entirely.

Reflecting on death has the potential to bring into relief that which matters most, and it can empower us to change how we live for the better. Ask anyone who is fully engaged in the process of dying. When our days are numbered, we value our relationships differently. We spend our time and money differently. We ponder life’s mysteries.

In ordinary times, we fool ourselves into thinking that the preparation for death can wait. But these are not ordinary times. When I was caring for hospitalized Covid patients this past Spring in New York City, they were frequently astonished that they had become so sick. They had not understood, as did Epicurus, that the art of dying is wrapped up in the art of living. But the pandemic has taught us that sickness and death do not happen only to other people. All of us must live with a view to our finitude.

This Black Friday, after the feasting has subsided and before the shopping begins, take a few minutes to talk with those you love about how to die well. Be frank about end-of-life wishes. Complete and sign documents.

At the same time, it also makes sense to talk about living. If Epicurus is right, to die well one must live well. And attending to what it means to live well — in light of the precarity of life — can make all the difference.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Living With Ghosts

By Mary O’Connor

“What’s your name?”

“Mary.”

“Mary what?

“O’Connor.”

“From where?”

“From here.”

“No, you’re not.”

“I’m your daughter.”

“No, you’re not. What’s your name? . . .”

“We should get him a tape recorder.”

“He’s human. He needs a human voice.”

“But his is almost gone.”

“That doesn’t matter.”

Staring into the face of an undead ghost in a green tweed jacket and flat-cap over toast and cornflakes is unnerving at the best of times; and traumatic at the worst. Especially when that ghost is your father. And the cornflakes have gone soggy.

But unlike gothic novels or films where ghosts happily offer themselves up as symbols of repressed memories, traces of crimes against innocents, and (usually) murderous pasts, this ghost has never crossed over into the realm of the metaphorical. Inconveniently, it decides to remain very, very human. Actually, that depends on your definition of human.

Even more inconvenient is the fact that this ghost refuses to follow the script and disintegrate with the morning light. Instead, it prefers to haunt the modern comforts of an electric armchair; swapping dreary castles for daytime television and crumbling dungeons for motorised beds.

And that’s just the start of my day living with a living ghost. Or Alzheimer’s as it’s otherwise known. Or, more correctly, my father’s Alzheimer’s.

Living with Alzheimer’s, both as a carer and sufferer, is a growing phenomenon in the UK. Often confused with dementia, Alzheimer’s refers to a physical disease which affects the brain while dementia is simply a term for a number of symptoms associated with the progressive decline of brain function. These symptoms can include memory loss, difficulty with thinking and problem solving, and challenges with language and perception. There are over 400 types of dementia—with Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia as the most common forms. According to the Alzheimer’s Society of the UK, dementia is now the leading cause of death in the UK with someone developing it every three minutes. Alzheimer’s is classified as a “life-limiting” illness according to the NHS, but sufferers can live for many years after the initial diagnosis, depending on the progression of the disease. Divided into three stages, early, middle, and late, the symptoms of Alzheimer’s gradually become more severe as the disease progresses and more parts of the brain are affected.

In the early stages, having Alzheimer’s as a companion wasn’t too unpleasant; the emptiness hadn’t fully taken over and I had more human than spectre to talk to. I could still pretend to have a normal(ish) life with only the minor inconvenience of a (mostly) present parent, despite the occasional wandering through doors unexpectedly and lunatic outbursts. The human part kept his smiling eyes, watching the world orbit around the sweat-stained tea-pot and apple tart. But the Alzheimer’s relentless erasure of my father left a morbid spectre sitting in his chair at the kitchen table.

In the middle stages, my father’s personality and identity dropped away like discarded clothes. His manner of speech was the first to surrender to the disease. Forgetting words rapidly metamorphosised into hours of repetitive questioning, as if seeking to ground himself in concrete knowledge of the now while his fingers grabbed vainly at a slipping sense of reality. The final stages of the disease witnessed his childish cries for help without knowing what or who he wanted.

“Gone childish” is an archaic term that was once used to describe dementia and Alzheimer’s sufferers before these diseases were better understood. Capturing the vulnerability these diseases inflict on their sufferers, the phrase sums up the centrality of memory to the human experience. If our identities are formed by our experiences, and these experiences are stored in our memories, shaping who we are and how we make decisions, what can we do when we have no memory? Without a roadmap of precedence, how can you plan for the future or know yourself without knowing how you got to where you are now? Like children, Alzheimer’s sufferers lose a sense of the past and futurity. They become transfixed in the present like ghosts trapped in limbo.

The last stages of my father’s disease cemented his role in the family home as the new phantasm. Like a well-behaved, conventional ghost he punctuated our nights with night-walking, ghoulish shrieks, hallucinations, and knocking on doors at all hours while the day-time witnessed empty eyes peering out from behind the safety of a purple blanket. Innocent of blame, our ghost blocked our escape from the house. For fear of hurting himself, we couldn’t leave him alone but grew resentful for being held hostage by a madman with no memory or awareness of his own actions.

After being stripped of memory and identity, my father’s Alzheimer’s left a shell of body; a ghastly reminder of the person that had once inhabited it. Bereft of the markers of humanity, this animated mannequin asked, “What makes up a human? Is it the mind? Or the body? And what happens when you take one from the other?”

Researchers have identified the cause of Alzheimer’s as the build-up of abnormal structures in the brain called ‘plaques’ or ‘tangles’. These structures cause damage to brain cells and can block neuro-transmitters, preventing cells from communicating with each other. Over time, parts of the brain begin to shrink with the memory areas most commonly affected first. Why these build-ups occur or what triggers them is not yet understood, but researchers now know that it begins many years before symptoms appear.

Ancient Roman and Greek philosophers associated the symptoms dementia with the ageing process. However, it was not until 1901 when the German psychiatrist, Alois Alzheimer, identified the first case of the disease. Medical researchers during the twentieth century began to realise that the symptoms of dementia and Alzheimer’s were not a normal part of ageing and quickly adopted the name of Alzheimer’s disease to describe the pattern of symptoms relating to this type of neurological degeneration.

No physical markers like the puckered lines of surgery scars or the uneven hobble of a game leg signposted my father’s declining health. But the slow creep of this living death brought on grief long before his body was expected to fail. Without the essence of the person, all of their quirks and curiosities, which once animated a familiar body, how do you grieve for someone’s loss before they have died? And how do you cope with the guilt?

This type of grief is usually referred to as anticipatory grief. It is a type of grief that is experienced prior to death or a significant loss. Typically, it occurs when a loved one is diagnosed with a terminal or life-threatening illness, but it can also happen in the face of a personal diagnosis. However, it can often trigger feelings of guilt because people feel ashamed for grieving their loved one’s death before they are dead.

With my father’s memory gone, my connection with him was broken. During the later stages of the disease he forgot my name and my existence. Fading from my life, his body remained as a perverse mockery of the person that had once inhabited it. Now all that haunts me are the memories of peering over barley stalks before the autumn harvests at a grizzled old farmer in a flat cap and tweed jacket, a hand reaching out to help guide the walk home.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Why Arun Shourie concludes that the ultimate preparation for death is simply love

The former Union minister and veteran journalist’s latest book, ‘Preparing for Death’, is both a contemplation of and an anthology on death

Arun Shourie is an unflinching seeker. He has an exemplary ability to face the toughest questions. After a bracing meditation on the problem of suffering in Does He Know a Mother’s Heart (2011), Shourie now turns to Preparing for Death. There used to be a joke that the purpose of literature is to prepare you for the good life, while the purpose of philosophy is to prepare you for the good death. But it is hard to understand our own extinction. Broadly speaking, two diametrically opposite views are invoked to reconcile us to death. One is that we don’t really die; in some form, through an incorporeal soul or something, we continue to exist. The other unflinchingly accepts that we just are evanescent matter and nothing else. Both approaches address the question of dying by simply saying “there is nothing to it.” There is something to this strategy, but it cannot make sense of the significance of life. It seems we can either make sense of life or of death, but not of both.

Shourie’s book takes a brilliantly different pathway. The book has three distinct themes. The first, the most powerful and meditative section of the book is not so much about death as the process of dying. He documents with detail, “great souls” experiencing the often painful dissolution of their own body — the Buddha, Ramkrishna Paramhansa, Ramana Maharshi, Mahatma Gandhi, and Vinoba Bhave, and, as a cameo, Kasturba. All of them give lie to Sigmund Freud’s dictum that no one can contemplate their own death. But what emerges from these accounts is not so much the conclusion that they all faced death unflinchingly; most of them have a premonition. It is also not about capturing the moment where the good death is leaving the world calmly. It is rather what the suffering body does to consciousness, all the memories and hard decisions it forces on us.

But the relationship between the body and consciousness goes in two different directions at once. On the one hand this suffering is productive: consciousness works through this pain. On the other hand, even the most exalted soul does not escape the utter abjection of the body. The most poignant moment in this section is not the calm and plenitude with which these exalted souls face death; it is the moments where even the most powerful souls are reduced to abjection by the constraints of the body. The only one rare occasion where Ramana Maharshi ever loses his cool is in his now utter dependence on others for most basic bodily functions. The problem of dying is not that you cannot ignore the body; it is that the body does not ignore you.

The second theme of the book is to take a sharp scalpel to false comforters of all religions and philosophies that promise the everlasting soul, or the preservation of bodies only to subject them to torment in hell. This metaphysical baggage makes dealing with death harder and is a total distraction. This section is less generous in its interpretive sympathies. The third theme of the book, interspersed in various parts, is about the discipline of dealing with your own body as it is in the process of dying. The book impressively marshals a variety of sources, from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, with its incredible imaginative exercises that make you take in the whole of existence, to Jain sources of Sallekhana, and various meditative techniques to inculcate a certain kind of mindfulness. But mostly one gets the sense that the ultimate preparation for death is simply love, something that can endow the evanescent moment with significance.

But this is a seeker’s book. It is in parts profound probing, honest but not dogmatic. Its immense value comes from the fact that the book is both a book and an anthology on death, with extracts from not just the words of those experiencing the process of dying, but an astonishing range of sources: from Fernando Pessoa to Michel de Montaigne, from yoga to the Tibetan Book of the Dead. For the politically inclined, there is an ambivalently revealing account of the Prime Minister’s visit to Shourie while he was in the ICU. All throughout, the book is laced with judiciously selected poetry: the startling moment where Gandhi recites the Urdu couplet to Manu: Hai baha- e-bagh-e duniya chand roz/ Dekh lo iska tamasha chand roz, a register you might associate more with Guru Dutt than Gandhi. There is a lot of Kabir, of Basho poetry and haikus. One stunning one: Circling higher and higher/At last the hawk pulls its shadow/From the world.

This haiku caught my attention because I happened to be reading a stunning essay by Arindam Chakrabarti at the same time, “Dream, Death and Death Within A Dream”, in Imaginations of Death and the Beyond in India and Europe (2018), a volume edited by Sudhir Kakar and Gunter Blamberger, that reads as a great philosophical complement to this one. That volume has a powerful piece by another brilliant philosopher, Jonardan Ganeri, on illusions of immortality that deals with a source Shourie cites at length: Pessoa. Chakrabarti’s essay ends with the insight of Yoga Vashishtha: To be born is to have been dead once and to be due to die again. Shourie is perhaps right: Can we really unravel what it means for the hawk to pull its shadow from the world? Does the shadow reappear if it flies lower?

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How Can We Bear This Much Loss?

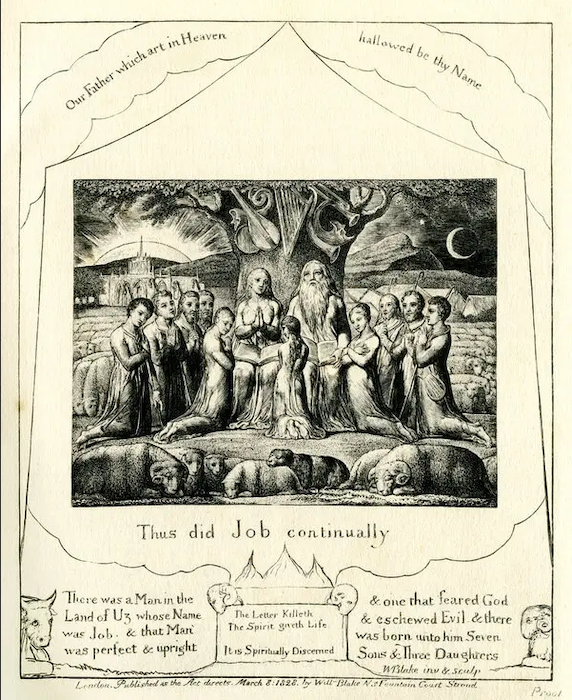

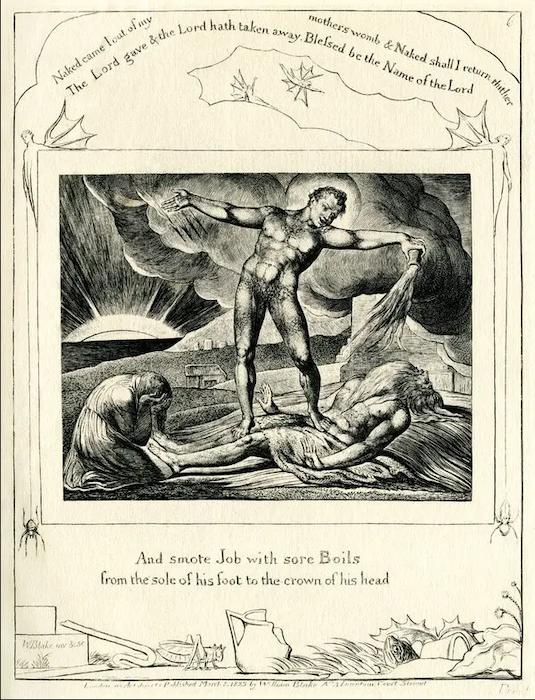

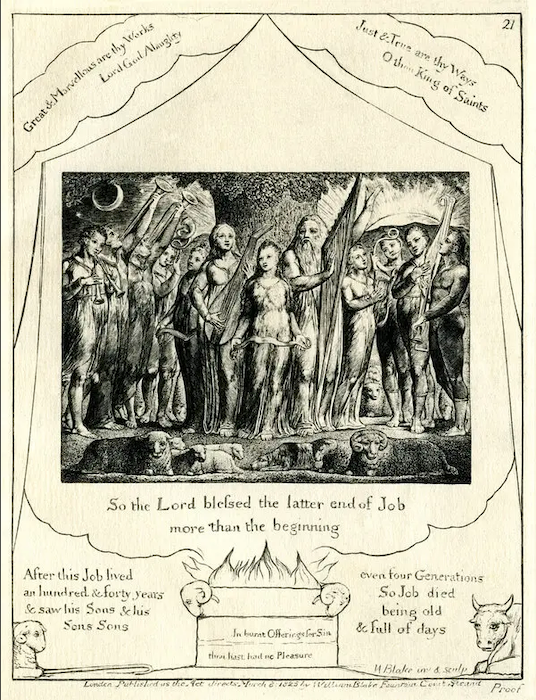

In William Blake’s engravings for the Book of Job I found a powerful lesson about grief and attachment.

By Amitha Kalaichandran

If grief could be calculated strictly in the number of lives lost — to war, disease, natural disaster — then this time surely ranks as one of the most sorrowful in United States history.

As the nation passes the grim milestone of 200,000 deaths from Covid-19 — only the Civil War, the 1918 flu pandemic and World War II took more American lives — we know that the grieving has only just begun. It will continue with loss of jobs and social structures; routines and ways of life that have been interrupted may never return. For many, the loss may seem too swift, too great and too much to bear, each story to some degree a modern version of the biblical trials of Job.

I thought of the biblical story of Job last month when I was asked to speak to the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation. How would I counsel others to cope with losses so terrifying and unfair? How could those grieving find a sense of hope or meaning on the other side of that loss?

In my research I found myself drawn to the powerful rendition of the Book of Job by the 18th-century British poet, artist and mystic William Blake, in particular his collection of 22 engravings, completed in 1823, that include beautiful calligraphy of biblical verses.

Job, of course, is the Bible’s best-known sufferer. His bounty — home, children, livestock — is taken cruelly from him as a test of faith devised by Satan and carried out by God. He suffers both mental and physical illness; Satan covers him in painful boils.

Job is conflicted — at times he still has his faith and trusts in God’s wisdom, and other times he questions whether God is corrupt. Finally, he demands an explanation. God then allows Job to accompany him on a tour of the vast universe where it becomes clear that the universe in which he exists is more complex than the human mind could ever comprehend.

Though Job still doesn’t have an explanation for his suffering, he has gained some peace; he’s humbled. Then God returns all that Job has lost. So, the story is, in large part, about the power of one man’s faith. But that’s not all.

The verses Blake chooses to inscribe on his illustrations suggest there’s more. In the first engraving we see Job’s abundance. Plate 6 includes the verse: “Naked came I out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return thither: The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away.”

So, the Book of Job isn’t just about grief or just about faith. It’s also about our attachments — to our identities, our faith, the possessions and people we have in our lives. Grief is a symptom of letting go when we don’t want to. Understanding that attachment is the root of suffering — an idea also central to Buddhism — can give us a glimpse of what many of us might be feeling during this time.

We can recall the early days of the pandemic with precision; rites that weave the tapestry of life — jobs, celebrations, trips — now canceled. In our minds we see loved ones who will never return. Even our mourning is subject to this same grief, as funerals are much different now.

In Blake’s penultimate illustration in this series Job is pictured with his daughters. Notably Blake doesn’t write out this verse from Job; instead he writes something from Psalm 139: “How precious also are thy thoughts unto me, O God! How great is the sum of them!” In the very last image, however, God has returned all he had taken from Job — children, animals, home, health and more. Here, Blake encapsulates Job 42:12: “So the Lord blessed the latter end of Job more than his beginning: for he had 14,000 sheep, and 6,000 camels, and 1,000 yoke of oxen, and 1,000 donkeys.”

Blake intentionally didn’t make the last image a carbon copy of the first, likely in order to reflect new wisdom: an understanding that we are more than just our attachments. The sun is rising, trumpets are playing, all signifying redemption. Job became a fundamentally changed man after being tested to his core. He has accepted that life is unpredictable and loss is inevitable. Everything is temporary and the only constant, paradoxically, is this state of change.

So, where does all of this leave us now, as we think back to how our attachments have fueled our grief, but perhaps also our faith in what’s to come? Can we look forward to a healthier, more just world? Evolution can sometimes look like destruction to the untrained eye.

I think it leaves us with a challenge, to treat our attachments not simply as the root of suffering but as fuel that, when lost, can propel us forward as opposed to keeping us tethered to our past. We can accept the tragedy and pain secondary to our attachments as part of a life well lived, and well loved, and treat our memories of our past “normal” as pathways to purpose as we move forward. We still honor our old lives, those we lost, our previous selves, but remain open to what might come. Creating meaning from tragedy is a uniquely human form of spiritual alchemy.

As difficult as it is now, in the midst of a pandemic, it is possible — in fact, probable — that after this cycle of pain we feel as individuals and collectively that we might emerge with a greater understanding of ourselves, faith (if you’re a person of faith), and our purpose.

The word “healing” is derived from the word “whole.” Healing then is a return to “wholeness” — not a return to “sameness.” Those who work in hospice know this well — the dying can be healed in the act of dying. But we don’t typically equate healing with death.

Ultimately, to me, that’s the lesson offered by Blake’s Job: understanding his role in a wider universe and cosmos, transformed in his surrender, and the release from the attachments to his old life. Job had the benefit of journeying across the universe to understand his life in a larger context.

We don’t. But we do have the benefit of being his apprentices as we begin to emerge from this period, and begin to choose whether it propels us forward or keeps us stuck in pain, and in the past.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

In his life and death, my uncle taught me the real meaning of bravery

For her Loading Docs short Going Home, film-maker Ashley Williams paid tribute to her late uncle Clive by learning to fly.

Some people say I was brave to fly. I tell them my Uncle Clive was the one who had courage.

He was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer at the age of 50. He had no choice about dying. But he made a choice about how and when he wanted to die.

When I was funded by Loading Docs to make a personal documentary about Clive, I knew I had to challenge myself to do something adventurous, something he would do. He always loved to fly, so what better way to honour him than take to the sky myself and paraglide.

This year marks 10 years since he passed. I wanted to make a film that both honoured Clive’s memory for those who knew him, and shared his story with those who didn’t. In a year when New Zealanders are voting on the End of Life Choice Act, I believed the timing was right, and could offer insight to those that need it.

In preparation for the documentary, as well as the flight, I buried myself in my uncle’s legacy – as a photographer, an adventurer, a scientist and a spiritual seeker. I dug out his old photos and read the letters he wrote over his final year, letters that were integral to the making of this documentary. What struck me most was his courage in facing a terminal illness, dealing with his own loss, yet managing and helping others in their grieving too. Now that is brave.

Making this film I learnt a lot more than just whether or not I could fly. I discovered it’s not just about the big, bold moments when we are brave. It’s about things like kindness in the face of adversity, being able to laugh when things don’t go to plan, standing up for what you believe in and being honest with yourself and others.

Clive taught me that life is about the little adventures along the way. So much of life is out of our control – there will always be the possibility the wind direction might change. So for the days you can, you fly! And oh, how I flew. Up there, among the clouds, being a bird. I realised why I had to do this and it changed me forever.

It also helped me understand what it must have been like for Clive, to have been caged in his bed near the end, watching out his window as the wind blew the clouds across the sky. To have known it was a perfect day to fly, or just go for a walk, but not be able to. When you’re that close to dying, surely you must know a thing or two about living. Clive was always the wise one.

Through Clive’s life and his decision about how he died, when he had only days to live, I hope viewers will consider those who no longer have a choice about whether they die or not, who are asking for the right to die with dignity.

I also want to encourage everyone to read the Act before voting. It’s designed for those suffering from a terminal illness that is likely to end their life within six months, for those who have significant and ongoing decline in physical capability, who have unbearable suffering that cannot be eased, and who are able to make an informed decision about assisted dying. This law could bring real support for people who need it in their time of pain and suffering, and in doing so also provide support and care for those left behind.

My hope is that if I ever face terminal illness I can do it with as much courage and grace as my Uncle Clive. I also hope I’ll have a choice that affords me the dignity I deserve.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How to Die (Without Really Trying)

A conversation with the religious scholar Brook Ziporyn on Taoism, life and what might come after.

By George Yancy

This is the fifth in a series of interviews with religious scholars exploring how the major faith traditions deal with death. Today, my conversation is with Brook Ziporyn, the Mircea Eliade professor of Chinese religion, philosophy and comparative thought at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Professor Ziporyn has distinguished himself as a scholar and translator of some of the most complex philosophical texts and concepts of the Chinese religious traditions. He is also the author of several books, including “The Penumbra Unbound: The Neo-Taoist Philosophy of Guo Xiang” and “Zhuangzi: The Complete Writings,” as well as two works on Tiantai Buddhism . — George Yancy

George Yancy: For many Westerners, Taoism is somewhat familiar. Some may have had a basic exposure to Taoist thought — perhaps encountering translations of the “Tao Te Ching” or Chinese medicine or martial arts or even just popular references to the concept of yin and yang. But for those who haven’t, can you give us some basics? For example, my understanding is that Taoism can be described as both a religious system and a philosophical system. Is that correct?

Brook Ziporyn: “Taoism” (or “Daosim”) is a blanket term for the philosophy of certain classical texts, mainly from Lao-tzu’s “Tao Te Ching” and the “Zhuangzi” (also known in English as “Chuang-tzu”), but also for a number of religious traditions that adopt some of these texts while also producing many other texts, ideas and practices. This can make it difficult to say what the attitude of Taoism is on any given topic.

What they have in common is the conviction that all definite things, everything we may name and identify and everything we may desire and cherish, including our own bodies and our own lives, emerge from and are rooted in something formless and indefinite: Forms emerge from formlessness, the divided from the undivided, the named from the unnamed, concrete things from vaporous energies, even “beings” from what we’d call “nothing.”

Some forms of religious Taoism seek immortal vitality through a reconnection with this source of life, the inexhaustible energy that gave us birth. Many forms of cultivation, visualization and ritual are developed, with deities both inside and outside one’s own body, to reconnect and integrate with the primal energy in its many forms.

The philosophical Taoism of the “Tao Te Ching” seeks to remain connected to this “mother of the world,” the formless Tao (meaning “Way” or “Course”), that is seemingly the opposite of all we value, but is actually the source of all we value, as manure is to flowers, as the emptiness of a womb is to the fullness of life.

In all these forms of Taoism, there is a stress on “return to the source,” and a contrarian tendency to push in the opposite direction of the usual values and processes, focusing on the reversal and union of apparent opposites. In the “Zhuangzi,” even the definiteness of “source” is too fixed to fully accommodate the scope of universal reversal and transformation; we have instead a celebration of openness to the raucous universal process of change, the transformation of all things into each other.

Yancy: In Taoism, there is the concept of “wu-wei” (“doing nothing”). How does this concept relate to what we, as human beings, should strive for, and how is that term related to an ethical life?

Ziporyn: Wei means “doing” or “making,” but also “for a conscious, deliberate purpose.” Wu-wei thus means non-doing, implying effortlessness, non-striving, non-artificiality, non-coercion, but most centrally eschewal of conscious purpose as controller of our actions.

So in a way the idea of wu-wei implies a global reconsideration of the very premise of your question — the status and desirability of striving as such, or having any definite conscious ideals guide our lives, any definite conscious ethical guide. Wu-wei is what happens without being made to happen by a definite intention, without a plan, without an ulterior motive — the way one does the things one doesn’t have to try to do, what one is doing without noticing it, without conscious motive. Our heart beats, but we do not “do” the beating of our hearts — it just happens. Taoism says “wu-wei er wu bu-wei” — by non-doing, nothing is left undone.

Theistic traditions might suggest that what is not deliberately made or done by us is done by someone else — God — and done by design, for a purpose. Even post-theistic naturalists might still speak of the functions of things in terms of their “purpose” (“the heart pumps in order to circulate the blood and keep the body alive”). But for Taoists, only what is done by a mind with a prior intention can have a purpose, and nature isn’t like that. It does it all without anyone knowing how or why it’s done, and that’s why it works so well.

Yancy: How does Taoism conceive of the soul?

Ziporyn: Taoism has no concept of “the” soul per se; the person has many souls, or many centers of energy, which must be integrated. All are concretizations of a more primal formless continuum of energy of which they are a part, like lumps in pancake batter. These are neither perfectly discontinuous nor perfectly dissolved into oneness.

Ancient Chinese belief regarded the living person as having two souls, the “hun” and the “po,” which parted ways at death. Later religious Taoists conceived of multitudes of gods, many of whom inhabit our own bodies — multiple mini-souls within us and without us, which the practitioner endeavored to connect with and harmonize into an integral whole.

Yancy: The concept of a soul is typically integral to a conceptualization of death. How does Taoism conceive of death?

Ziporyn: In the “Zhuangzi,” there is a story about death, and a special friendship formed by humans in the face of it. Four fellows declare to each other, “Who can see nothingness as his own head, life as his own spine, and death as his own backside? Who knows the single body formed by life and death, existence and nonexistence? I will be his friend!” We go from formlessness to form — this living human body — then again to formlessness. But all three phases constitute a single entity, ever transforming from one part to another, death to life to death. Our existence when alive is only one part of it, the middle bit; the nothingness or formlessness before and after our lives are part of the same indivisible whole. Attunement to this becomes here a basis for a peculiar intimacy and fellowship among humans while they are alive, since their seemingly definite forms are joined in this continuum of formlessness.

The next story in the “Zhuangzi” gives an even deeper description of this oneness and this intimacy. Three friends declare, “‘Who can be together in their very not being together, doing something for one another by doing nothing for one another? Who can climb up upon the heavens, roaming on the mists, twisting and turning round and round without limit, living their lives in mutual forgetfulness, never coming to an end?’ The three of them looked at each other and burst out laughing, feeling complete concord, and thus did they become friends.”

Here there is no more mention of the “one body” shared by all — even the idea of a fixed oneness is gone. We have only limitless transformation. And the intimacy is now an wu-wei kind of intimacy, with no conscious awareness of a goal or object: They commune with each other by forgetting each other, just as they commune with the one indivisible body of transformation by forgetting all about it, and just transforming onward endlessly. Death itself is transformation, but life is also transformation, and the change from life to death and death to life is transformation too.

Yancy: Most of us fear death. The idea of the possible finality of death is frightening. How do we, according to Taoism, best address that fear?

Ziporyn: In that story about the four fellows, one of them suddenly falls ill and faces imminent death. He muses contentedly that after he dies he will continue to be transformed by whatever creates things, even as his body and mind break apart: His left arm perhaps into a rooster, his right arm perhaps into a crossbow pellet, his buttocks into a pair of wheels, his spirit into a horse. How marvelous that will be, he muses, announcing the dawn as a rooster, hunting down game as a pellet, riding along as a horse and carriage. Another friend then falls ill, and his pal praises the greatness of the process of transformation, wondering what he’ll be made into next — a mouse’s liver? A bug’s arm? The dying man says anywhere it sends him would be all right. He compares it to a great smelter. To be a human being for a while is like being metal that has been forged into a famous sword. To insist on only ever being a human in this great furnace of transformation is to be bad metal — good metal is the kind that can be malleable, broken apart and recombined with other things, shaped into anything.

I think the best summary of this attitude to death and life, and the joy in both, is from the same chapter in “Zhuangzi”:

This human form is just something we have stumbled into, but those who have become humans take delight in it nonetheless. Now the human form during its time undergoes ten thousand transformations, never stopping for an instant — so the joys it brings must be beyond calculation! Hence the sage uses it to roam and play in that from which nothing ever escapes, where all things are maintained. Early death, old age, the beginning, the end — this allows him to see each of them as good.

Every change brings its own form of joy, if, through wu-wei, we can free ourselves of the prejudices of our prior values and goals, and let every situation deliver to us its own new form as a new good. Zhuangzi calls it “hiding the world in the world”— roaming and playing and transforming in that from which nothing ever escapes.

Yancy: So, through wu-wei, on my death bed, I should celebrate as death isn’t an ending, but another beginning, another becoming? I also assume that there is no carry over of memory. In other words, in this life, I am a philosopher, male, etc. As I continue to become — a turtle, a part of Proxima Centauri, a tree branch — will I remember having been a philosopher, male?

Ziporyn: I think your assumption is correct about that: There is no expectation of memory, at least for these more radical Taoists like Zhuangzi. This is certainly connected with the general association of wu-wei with a sort of non-knowing. In fact in the climax of the same chapter as we find the death stories just mentioned, we find the virtue of “forgetting” extolled as the highest stage of Taoist cultivation — “a dropping away of my limbs and torso, a chasing off my sensory acuity, dispersing my physical form and ousting my understanding until I am the same as the Transforming Openness. This is what I call just sitting and forgetting.”

And the final death story there describes a certain Mr. Mengsun as having reached the perfect attitude toward life and death. He understands nothing about why he lives or dies. His existence consists only of waiting for the next unknown transformation. “[H]is physical form may meet with shocks but this causes no loss to his mind; what he experiences are morning wakings to ever new homes rather than the death of any previous realities.”

The freshness of the new transformation into ever new forms, and the ability to wholeheartedly embrace the new values that go with them, seems to require an ability to let go of the old completely. I think most of us will agree that such thorough forgetting is a pretty tall order! It seems that it may, ironically enough, require a lifetime of practice.

Yancy: Given the overwhelming political and existential global importance of race at this moment, do you have any reflections on your role as a white scholar of Taoism? In other words, are there racial or cultural issues that are salient for you as a non-Asian scholar of Eastern religious thought?

Brook Ziporyn: A very complex question, probably requiring a whole other interview! But my feeling is that, when dealing with ancient texts written in dead languages, the issue is more linguistic and cultural than racial. This goes for ancient Greek, Hebrew, Sanskrit and Latin texts as well as for ancient Chinese texts, all of which bear a complex historical relation to particular living communities and their languages, but all of which are also susceptible to fiercely contested interpretations both inside and outside those communities.

I think it’s a good thing for both Asian and non-Asian scholars to struggle to attain literacy in the textual inheritances of both the Asian and the non-Asian ancient worlds, which is “another country” to all of us, and to advance as many alternate coherent interpretations of them as possible. These interpretations will in all cases be very much conditioned by our particular current cultural situations, and these differences will certainly be reflected in the results — which is a good thing, I think, as long as we remain aware of it.

Writing about Taoism in English, one is speaking from and to an English-reading world. Doing so in modern Chinese, one is speaking from and to a modern-Chinese-reading world. Working crosswise in either language, as when a culturally native Anglophone like myself writes about Taoism in modern Chinese, or when a native Mandarin speaker writes in English about Taoism, or for that matter in either English or Chinese about ancient Greek philosophy or the Hebrew Bible, the situation will again differ, and the resulting discussion will reflect this as well.

In terms of the dangers of Orientalism, though, what I think must be especially guarded against is making any claim that whatever anyone may conclude about any particular ancient Chinese text can give any special insight into the politics, culture, or behavior of modern Chinese persons, communities or polities. The historical relations between modern and ancient cultural forms are simply too complex to think that the former can give one any right to claim any knowledge about the latter.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!