A Practical Approach to Death

Dying with compassion means having a plan in place for those left behind. A practitioner recounts how she navigated the process with her dharma friends.

By Rena Graham

As a Tibetan Buddhist practitioner, I am constantly reminded that we never know when death might approach, but for years, I’d avoided dealing with one of the most practical aspects of death—the paperwork. I was not alone: Roughly half of all adults in North America do not have a living will. Then recently, I suffered a near-fatal illness that left me viscerally aware of how unprepared for death I was, and I made a pledge with two of my friends to get ready to leave our bodies behind for both ourselves and the people who survive us.

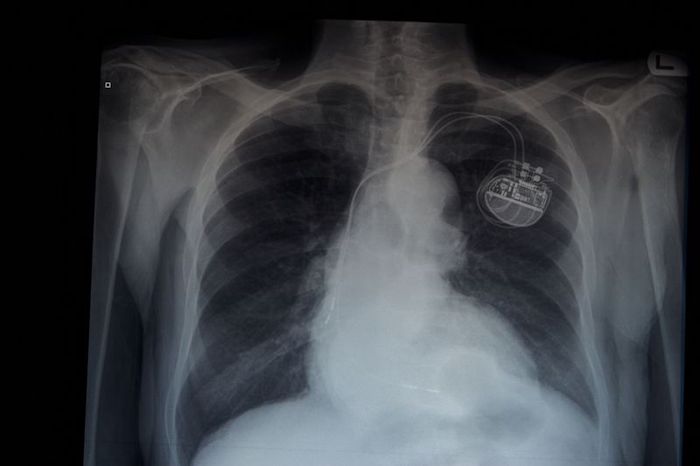

Bridging the end of December 2017 and the beginning of January 2018, I spent a month in a Vancouver, British Columbia hospital with a bacterial lung infection that had also invaded my pleural cavity—the first time I’d come down with a severe illness. After ten days in an intensive-care unit, I was moved to a recovery ward where I suffered a relapse. I spent my 62nd birthday, Christmas, and New Years with strangers in the hospital.

One night in the ICU, while I was partly delirious and falling in and out of sleep, I had a vision of a deceased friend reaching out to me. From what felt like disengaged consciousness, I looked down at my body on the hospital bed and realized I wasn’t ready to die. I hadn’t studied my lama’s [teacher’s] bardo teachings to navigate the intermediate state between death and rebirth, and did not want to take that journey without a road map. It didn’t matter whether this was a drug-fueled hallucination or an actual near-death experience. The important thing is that I rejected death, not out of fear, but through a recognition of the dreamlike nature of reality. After this experience, I felt that my attachment to this life and the things in it had diminished. I no longer wanted to ignore what came next. I wanted to be prepared.

When I told my friends Liv and Rosie about this vision, we agreed to study the bardo teachings together once I’d had a couple of months of recuperation. By March, however, our plans shifted. Rosie had heard about a man (I’ll call him Ben) who had died on Lasqueti Island, an off-the-grid enclave in Canada’s Southern Gulf Islands that a local cookbook once described as “somewhere between Dogpatch and Shangri-La.” He had left his closest friends without any instructions. They had no idea if he had a family or where they might be.

“And he left an old dog behind!” Rosie said, “Can you imagine?”

“Not the bodhisattva way to die,” I replied, referring to the Buddhist ideal of compassion. I also imagined what mess I might have left, had I not made it.

Promising they would never leave others in such a quandary, Ben’s closest friends created a document called the Good to Go Kit, which detailed information required for end-of-life paperwork. (It is now sold at the Lasqueti Saturday market to raise funds for their medical center.)

“I’ve been wanting to make a will for 20 years,” said Liv, who would soon turn 70, “but research throws me into information overload, which adds to the emotional overwhelm I feel just thinking about it.”

“What if we did this together instead of studying the bardo?” suggested Rosie, who was in her early 50s.

Writing a will, figuring out advanced healthcare directives, and noting our final wishes didn’t have the mystical lure of bardo teachings, but we set that aside for a year while we took on this more practical area of inquiry.

To use our time wisely, we set several parameters in place. We decided to meet one weekend a month to allow time for research and reflection between meetings, and we chose to keep our group small for ease of scheduling and to allow us to delve deeper into each topic.

“I’d like this to be structured,” said Liv, “so it doesn’t devolve into a social event.”

Rosie and I agreed but we knew better than to believe there didn’t need to be some socializing. She offered her place for the first meeting and said she’d cook.

“We’ll get our chit-chat out of the way over dinner,” she said. “Since we can all be a little intimidated by this process, we have to make it fun.”

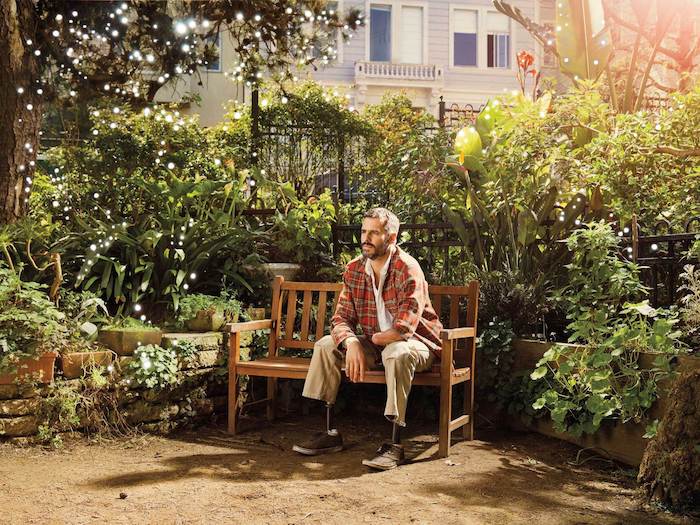

Later in March at Rosie’s garden suite, we sat down to dinner and Liv passed out copies of “A Contemplation of Food and Nourishment,” which begins with the appropriate words: “All life forms eat and are eaten, give up their lives to nourish others.” The prayer was written by Lama Mark Webber, Liv and Rosie’s teacher in the Drikung Kagyu school. (I also study with Lama Mark, although my main teacher, Khenpo Sonam Tobgyal, is in the Nyingma lineage.) Turning our meetings into sacred practice seemed the obvious container to keep us on topic.

After dinner, Rosie rang a bell, we said a refuge prayer and recited the traditional four immeasurables prayer to generate equanimity, love, compassion, and joy toward all sentient beings.

We traded our prayers for notebooks and reviewed our Good to Go Kit. Rosie smiled at the expected question of pets—including the name of the person who would be caring for the pet, the veterinarian and whether money had been set aside for their expenses. The form also asked whether we had hidden items or buried treasure.

Liv laughed and said, “People still bury strongboxes in their backyards?”

My answer was more prosaic: “Storage lockers.”

Rosie, Liv, and I are all single and childless. We are all self-employed and independent and have chosen Canada as our adopted homeland, meaning we have no family here. So we considered what roles friends might play and focused on those who were closer geographically than sentimentally.

Pulling them in to act on our behalf seemed like such a “big ask” as Rosie said, but it was time to get real about our needs. The three of us shared our feelings about involving friends outside the dharma versus those within.

When I was in the ICU, my friend Diane visited on several occasions and later told me she remained calm until she reached her car, where she cried uncontrollably. In marked contrast, my dharma friend Emma calmly asked what I needed and didn’t make much of a fuss. My Buddhist friends tend to view death as a natural transition from one incarnation to the next, while other friends may see it in more dire terms: as a finality or even failure. For end-of-life situations, asking non-Buddhist friends for limited practical support seemed kinder for all involved.

We started to familiarize ourselves with the responsibilities of someone granted power of attorney for legal and financial proxy and enduring power of attorney for healthcare. Months later, we agreed our network of “dharma sisters” would be the perfect fit. While we hope to maintain our ability to make decisions for ourselves, should we require long-term care, we felt the baton could be passed between a dozen or so trustworthy women. We have since spoken casually about this with a number of these women and have made plans to organize a get-together and discuss our plans in greater detail, offering reciprocal support for what the Buddhist author Sallie Tisdale calls “the immeasurable wonder and disaster of change.”

We concluded our five hours together by dedicating the merit and reciting prayers of dedication and aspiration. Long-life prayers for our lamas were offered, a bell rung, and heads bowed. Without the need for further conversation, we made our way into the chilly spring evening, silently reflecting on our new endeavor.

The next meeting and those following included menus and discussions that varied widely. Our research grew monthly with documents from government agencies, legal and trust firms, and funeral homes. None of which felt specific to Buddhist practitioners, until Rosie told us about Life in Relation to Death: Second Edition by the late Tibetan teacher Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche. This small book is out of print, but I purchased a Kindle copy. In the introduction, Chagdud Tulku, a respected Vajrayana teacher and skilled physician, reminds us that “[t]here are many methods, extraordinary and ordinary, to prepare for the transformation of death.” A book of Buddhist “pith instruction,” it includes in its second edition appendices that above all I found most valuable. These include suggested forms for “Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care,” “Advance Directive for Health Care (Living Will),” “Miscellaneous Statements for Witnesses, Notary and Physician,” and “Letter of Instructions.” It even includes a wonderful note for adding your ashes to tza-tsas, small sacred images stamped out of clay. We loved that idea, though we couldn’t imagine asking friends to go to that extent to honor our passing.

We decided to use a community-based notary public to draw up our wills, but with further research, Liv realized she could also hire them to act as her executor, rather than use her bank. She found someone experienced and enjoyed the more personable experience. In contrast, Rosie and I’ve decided to pay friends now that we’ve found ways to simplify that process for them.

Memorial Societies are common in North America and help consumers obtain reasonably priced funeral arrangements. Pre-paying services at a recommended funeral home allows us to leave funds with them for executor expenses, should our assets be frozen in probate. End-of-life insurance “add-ons” we like include travel protection—should we die away from home—and a final document service to close accounts and handle time-consuming administrative tasks.

In her book Advice for Future Corpses (and Those Who Love Them): A Practical Perspective on Death and Dying, Sallie Tisdale says, “Your body is the last object for which you can be responsible, and this wish may be the most personal one you ever make.” Traditionally in Tibetan Buddhism, the edict is to leave the body undisturbed for three days after death so your consciousness has time to disengage. Tisdale states that American law generally allows you to leave a body in place for at least 24 hours and that while a hospital might want to give you less time, you might be able to negotiate for more.

We then turned to the thorny topic of organ donation, with Rosie and Liv both deciding against. Knowing someone would soon be taking a scalpel to your cadaver would not enhance the peaceful mind they hope to die with, while my view was just the opposite. Besides gaining merit through donation, that same scalpel image provides great motivation to leave the body quickly.

While reading Tisdale’s chapter titled “Bodies,” I began entertaining thoughts of a green burial, but after months of discussion, I ended up where we all started: with expedient cremations. Rosie wanted her ashes buried and a fragrant rose bush planted on top. Liv and I were more comfortable in the water and decided our ashes would best be left there, but not scattered to ride on the wind. We selected biodegradable urns imprinted with tiny footprints. Made of sand and vegetable gel, they dissolve in water within three days, leaving gentle waves to lap our remnants out to sea.

By getting past the practical and emotional aspects surrounding death, Liv has found herself in a space of awe.

“There’s a wow factor to dying that I can now embrace,” she said.

Rosie no longer worries about who will care for her in later years. Without that insecurity, she’s left with a yearning to be as present for the dying process as possible. And I have found that my understanding of life’s importance as we reach toward enlightenment has been heightened.

Our small sangha still meets monthly and is now studying bardo teachings in our ongoing attempt to create compassionate dying from compassionate living. As we have continued with our arrangements, we’ve reflected on what we gained from our meetings. We feel blessed for the profound level of intimacy and trust we now share. We have a deeper regard for other friendships and feel enveloped by an enhanced sense of community. And we all feel more cared for.

As Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche wrote in Life in Relation to Death: “Putting worldly affairs in order can be an important spiritual process. Writing a will enables us to look at our attachments and transform them into generosity.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!