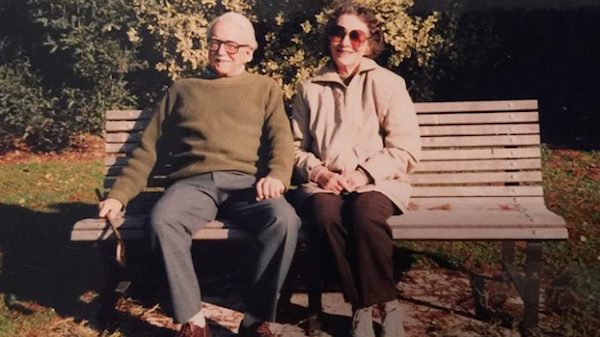

[O]n a cold winter morning, Phil Estes gets into the private ambulance he’s hailed for the more than two-hour journey to Spokane, all 99 pounds of the former Hanford engineer clinging to his frail 6-foot-tall frame as his gurney is secured in the vehicle.

He’s taking this trip not to save his life, but to be able to end it. As weak as Estes is, this is his last resort.

The 81-year-old is several years into his fight against colon cancer. He can barely sit up for five minutes at a time, let alone take care of himself. He’s in pain, it’s hard to breathe and the cancer that has riddled his body is going to kill him. So he’s done.

He wants to take “the pill.”

“I’ve lived a long life, a happy life,” Linda Estes recalls her dad telling her family at the time. “I want you to go on with your life, but I’ve thought it all through, and this is the best option.”

But as his family would soon learn, getting a lethal dose of medication, which is legal under Washington’s Death with Dignity Act, involves much more than a single pill. And in Eastern Washington, it can mean long roadtrips to find doctors and pharmacies willing to validate a patient’s terminal illness and fill a fatal prescription.

In the 10 years since voters passed the Death with Dignity Act, the vast majority of terminal patients who have opted to die under the law lived in Western Washington — more than 90 percent of cases most years — despite Eastern Washington accounting for more than 20 percent of the state population.

The discrepancy between the two sides of the Cascades, experts say, is largely due to access: Even those who can cover thousands of dollars in out-of-pocket costs aren’t guaranteed to live in an area where a doctor or hospital system is willing to participate.

In Estes’ case, Dr. David Jones had been working with him for years and was willing to learn how to sign off as the attending physician and write him a prescription. That meant Estes just needed another consulting doctor to agree he was mentally competent, deathly ill and not being coerced to get the life-ending medication.

But Jones learned that participating would violate policy at Kadlec, the Tri-Cities hospital system where he works, and he feared he might lose his job. The previously secular system had recently been acquired by Providence, a Catholic health-care system that generally doesn’t allow its employees to participate under the rules of the act.

So the family scrambled to find other doctors.

“We called everybody we could think of,” Linda Estes recalls. “At one point my mother was carrying all the cellphones and the house extension in a bag with her, so whoever called, she could answer them.”

Eventually, with assistance from End of Life Washington, a Seattle-based organization that helps people navigate end-of-life options, they got in touch with a Spokane doctor willing to sign the attending paperwork, and a local physician agreed to handle the consulting role. But the Spokane doctor wanted to diagnose Estes in person, spurring the $1,400 contracted ambulance ride from Richland to Spokane.

After an exhausting day of appointments, Estes got his prescription.

“I got out to the ‘cabulance,’ and I put the bag in dad’s hands,” Linda Estes says. “He grabbed that little [prescription] bag and his whole body relaxed. He’d been so afraid that at the last minute, that this decision that was his to make would be snatched from him.”

Estes took the medication at home Jan. 4, 2016, fell asleep and died peacefully with his daughter holding his hand.

But Linda Estes questions why it was so difficult to access something that was legal, especially when her father’s doctor was OK with the decision.

“My mom and I were able to accomplish this because we had the financial means and educational resources,” she says. “What do people do who don’t have these kind of resources? It shouldn’t be this hard.”

So she’s joining efforts to make the process easier for others and ensure physicians who want to sign off can do so.

TERMINAL CHOICES

Washington’s role in nationwide right-to-die efforts has a complicated history. In 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed a Washington state law that made physician-assisted suicide a felony. The court held that the law was fine, but also left the door open for states to pass laws allowing the practice if it wouldn’t violate their own constitutions.

That same year, Oregon became the first in the nation to enact its Death with Dignity Act.

A decade later, nearly 58 percent of Washington state voters approved their own version of the act, making Washington the second state in the country to allow the practice. Assisted suicide is still illegal under state law, but under the Death with Dignity Act, people who are already dying and meet the qualifications are not considered to be committing suicide — their underlying illnesses are listed as the cause of death on death certificates.

Since then, three other states — Vermont (in 2013), Colorado (2016) and California (2016) — and the District of Columbia (2017) have also legalized it. Opponents have filed various challenges in court, but each of the laws have been allowed to move forward. Montana hasn’t passed a similar law, but the state’s Supreme Court determined in a 2009 case that nothing in Montana law prohibits physicians from participating. That means about a sixth of the U.S. population lives in a state where the process is legal, and several states are currently considering similar bills.

The majority of American adults believe that someone has a moral right to end their life if they are suffering great pain with no chance for improvement (62 percent), or have an incurable disease (56 percent), according to a 2013 Pew Research survey on end of life. However, only 47 percent approved of laws allowing doctors to prescribe lethal medication to terminal patients.

How that process is referenced largely depends on viewpoint: Opponents typically refer to it as “physician-assisted suicide” or “euthanasia” (mercy killing), while proponents tend to use “death with dignity” or “physician aid-in-dying.”

Many opponents, including large sectors of the medical field and religious organizations, consider the act a crime or immoral. Some worry there could be a slippery slope: If patients think they are a burden on their families, they may feel pressured to die sooner; or insurance companies could decide it is cheaper to pay for fatal medication than further treatment. In summer 2016, Pope Francis told medical leaders that physician-assisted suicide was “false compassion.”

“Frailty, pain and infirmity are a difficult trial for everyone, including medical staff. They call for patience, for ‘suffering-with.’ Therefore, we must not give in to the functionalist temptation to apply rapid and drastic solutions, moved by false compassion or by mere criteria of efficiency or cost effectiveness,” the Catholic News Agency reported Francis saying. “The dignity of human life is at stake.”

But proponents point to very specific protections written into the law. More than one physician needs to determine someone is terminally ill and not being coerced. At least one witness to the request for medication must not be related or stand to gain financially from the person’s death. There are mandatory waiting periods and the chance to rescind a request before a prescription is filled.

In states where it is not legal, people sometimes take extreme measures to die on their own terms.

Lacie Agidius was drinking coffee with her father in Lewiston, Idaho, when he received the worst call of his life.

Her grandfather was on the other end. He’d dressed in his best Sunday suit, organized important documents and was calling to make sure someone knew where a few things were on the family farm before taking his own life.

“He had told [my dad], ‘I want you to know, I don’t want to freak you out: Today is the day. I’m getting ready to walk down to the car,'” Agidius says. “He said, ‘This is not a call for help. This is absolutely what I want to do.'”

After being diagnosed with prostate cancer, her grandfather chose not to treat it. For months, he’d told his family he was getting his affairs in order and planned to take things into his own hands if it came to the point where he was in too much pain and couldn’t care for himself, but they’d largely brushed him off or were in denial, Agidius says.

Then came the call. In an awful shock to Agidius’ father, not only did her grandfather warn him not to call authorities, but he also said if he wasn’t successful, he wanted them to “finish the job.” A half-hour drive away, her father refused and said, “You don’t need to do this.”

“The whole conversation was awful,” Agidius says. “That long car ride for my dad and brothers, not knowing what they were going to find, that whole experience was so traumatic.”

By the time they arrived, it was too late.

Agidius, who now works in hospice care in the Spokane-Coeur d’Alene area, says she wishes that life-ending meds would have been an option for her grandfather, as it would’ve made things easier on everyone to know what was coming, and would have been less frightening for him, as it would have provided certainty.

She still lives in Idaho, where lawmakers made physician-assisted suicide a felony in 2011, partly in response to efforts similar to those that legalized the practice in neighboring states.

“It is something that is hard for people on the Idaho side to think we wouldn’t have that option,” she says. “You plan that date, then you can have time with that person, you know it’s happening. You can say those things you want to say and not have a shocking situation.”

PLANNING FOR THE UNKNOWN

Jessica Rivers, an End of Life Washington volunteer

Aside from the planning required by mandatory waiting periods, people with life-ending meds tend to plan out the process with family, and in each of the cases volunteer client adviser Jessica Rivers has worked on, they tried to say meaningful goodbyes to their loved ones.

Rivers, who lives near Palouse, Washington, has been a volunteer with End of Life Washington for about four years, working with families in Pullman, Spokane and rural communities in the region.

In the first case she worked, she and other End of Life volunteers arrived on the date their client selected to find his home full with family, friends and neighbors.

“They had food and drink and had all been having his celebration of life that morning,” Rivers says. “It was really remarkable, because we just let them take their time and do what they needed to do.”

The man, dying of aggressive cancer, gave his own eulogy, and everyone surrounded him as he lay down in bed, took the medication and talked them through how he felt before falling asleep. In the quiet, someone started singing “Amazing Grace,” and everyone cried.

“It was very powerful for me, and it was very gentle and very peaceful for him,” Rivers says.

For her, the choice to get involved in end-of-life care started about 20 years ago, when she cared for her mother, who was dying of pancreatic cancer.

“I remember my mom looking at herself in the mirror one morning, and the cancer had just ravaged her body,” Rivers says. “She was actually, amazingly enough, OK with dying, but she wasn’t OK with the process of getting there, and I think that’s true for most of the folks I’ve been with at End of Life.”

Of the 25 cases she’s been involved with through the organization, each patient died, though only six of them decided to take the medication.

“The majority of them told me, ‘I may or may not use this, but it gives me peace of mind,'” Rivers says. “And one of the things I tell them on that first visit when I meet them is ‘I’m not invested at all in whether they take this or not.'”

As a volunteer, she typically meets with families a few times, offering information on what the process may look like, encouraging clients to get on hospice care, and talking about death and the dying process, which is new to many people.

“I think that helps reduce fear,” she says. “My little piece of advice to family members is try not to let the fear and grief interfere in the days to come that you have left with your loved one. Try to really balance that fear and grief with love and gratitude.”

Rivers, who spent several years working in hospice, feels people aren’t supported enough through the end of their lives, which can be distressing. One dying man Rivers spoke to last year blurted out in front of his adult children that if he couldn’t for some reason access lethal medication under Washington’s law, he had hunting guns in his basement.

“The fear and distress this caused his children was so obvious and apparent,” Rivers says. “But the reality is people who are desperate can do dramatic things, and that’s one of the reasons this law is so important. People should not have to feel desperate.”

EAST SIDE, WEST SIDE

Of the more than 1,100 people who are known to have died after getting prescriptions for lethal medication under Washington’s law from 2009 through 2016, fewer than 150 lived east of the Cascades, according to data compiled by the Washington State Department of Health. Not all of those people took the medication.

About three-quarters of people who got prescriptions had cancer, while the rest were mostly people with neurodegenerative diseases such as Lou Gehrig’s disease or respiratory or heart disease.

People who use the law account for only about two of every 1,000 deaths in Washington, says Sally McLaughlin, executive director of End of Life Washington. Of the more than 54,000 people who died in the state in 2015, 166 used the medication, putting the number of deaths in that category slightly above the 141 people who died from the flu the same year.

“It’s not like it’s a rampant number of people, but the issues with access have to do with several things,” she says. “One is access to physicians who can or are able to prescribe life-ending medications in a more conservative environment. There are a lot of physicians who don’t even want to think about administering life-ending medications.”

Secondly, many doctors are not allowed to participate under the rules of their employers. Patients often have to form new relationships with doctors when they’ve got little time left.

Aside from the population size accounting for part of the difference, many people east of the mountains just don’t know the law exists, says Dr. Raleigh Bowden, who lives in Twisp and works as a volunteer medical adviser with End of Life.

“In my personal experience, a lot of people don’t know about the law,” Bowden says. “In fact I talked to one pharmacist [last] year who didn’t know we had a law.”

Patients need both a prescribing doctor and a consulting physician, who ensures the person isn’t being coerced. To be eligible, the patient must be a Washington resident, have about six months or less to live, and understand that there are other options, Bowden says.

Ideally consulting physicians see someone in person, but in rural areas, sometimes they have to use other options like electronic communication. From Twisp, Bowden will sometimes serve in the consulting role via Skype, as that part of the process mostly involves going over a checklist with the patient.

Attending doctors almost always want to see the patient in person, Bowden says, and it’s better if they’ve already had a relationship. Jones, Estes’ doctor, says it was the fact he’d known him for eight years that made him comfortable with the idea of supporting his decision.

“It was the perfect situation for me to say, ‘Wow, how could I deny this?'” Jones says. “Whatever my beliefs were, I was a physician in the state of Washington where this was legal. It took the politics out of it for me until the very end when I realized I might be at risk of losing my job.”

Aside from physicians, the medication itself can pose problems.

End of Life Washington recommends one of two prescriptions. The first and cheapest runs about $700, but needs to be made in a compounding pharmacy, which often isn’t available in rural areas, Bowden says.

The second and most expensive option involves opening up about 100 capsules of Seconal, once regularly prescribed as a sleeping pill, and mixing the contents with juice or something the patient can drink. With only one manufacturer making the drug anymore, the price for that dosage has gone up from a few hundred dollars when Washington’s law started to more than $3,000.

“If you’re poor — and I have yet to see an insurance company pay for this, though I hear some will — then the cost falls into the lap of the patient or their family,” Bowden says. “That’s a barrier if you come from a poor part of the state.”

The most common reasons Washington patients told their doctors they wanted life-ending meds was because they were losing autonomy and the ability to engage in activities that make life enjoyable, with 84 percent to 100 percent of patients citing those two reasons every year from 2009 to 2016, the most recent for which state data has been released.

In contrast, inadequate pain control or concern about it was cited by 25 percent to 41 percent of patients, and only 2 percent to 13 percent cited concerns about the cost of medical treatment.

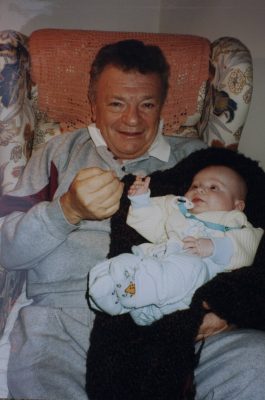

For many years, Pat and Melinda Hannigan lived in Seattle, where Melinda was an artist and Pat worked as a tanker pilot in Puget Sound. Melinda was hanging some of her paintings for a show in Tacoma when she had a shooting pain go through her head and half of her face became paralyzed. What they initially thought was a stroke was actually due to a tumor, part of an aggressive cancer that would spread to other parts of her body.

Hannigan tried every treatment available, but after years of radiation, chemotherapy and other therapies destroying her body, her quality of life was awful, Pat Hannigan says.

She could barely swallow or speak, was put on a feeding tube for more than a year and was confined to a wheelchair. After going on hospice care in the home the couple had built in Twisp, she decided to take the medication.

When it came time, Pat had to drive an hour to Omak to get the pills, which cost them about $4,400 out of pocket.

Hannigan shared a final dinner with her kids and grandkids and was surrounded by family when she took the lethal dose in July of 2016.

Pat Hannigan says it was the right decision for his wife and was in keeping with her choices to accept or decline treatment at every step of her illness. Still, he hasn’t spoken to many people about the experience, in part because he doesn’t want to influence others, who need to make that choice for themselves. However, he thinks those who oppose the law don’t understand what it’s like.

“I hear people criticize it and I think to myself, ‘They have never been through an experience like this in their lives,'” Hannigan says. “It’s really easy for them talk based on their religious beliefs or their philosophical principles, but if you live through four years of absolute, total hell, with no hope, Death with Dignity is an awesome thing.”

NOT FOR EVERYONE

Policies about physician participation under the act vary even within the same system.

For example, Providence physicians in Spokane are not allowed to participate under the rules of the act in any way, even though physicians at Swedish, a Providence-affiliated hospital in Seattle, are allowed to if they choose.

“We respect the rights of patients and their care team to discuss and explore all treatment options and believe those conversations are important and confidential. As part of a discussion, requests for self-administered life-ending medication may occur, but our providers do not participate in any way in assisted suicide,” writes Liz DeRuyter, director of external communications for Providence Health & Services. “We provide all other requested end-of-life and palliative care and other services to patients and families.”

MultiCare, the other large service provider in Spokane, does allow its physicians to participate as attending and consulting physicians, and they may write prescriptions. However, no MultiCare physicians or pharmacies can help patients fill the prescriptions, meaning they need to find another pharmacy to fill it.

In her efforts to increase access, Linda Estes is working with Providence to change the policy at its Tri-Cities affiliate hospital to allow physicians to participate under the law, even if that means doing so outside of the scope of the hospital system. She’s been in contact with a Providence attorney about helping draft that policy, which is under consideration.

Estes says she’s passionate about making that change because when a family member is dying, the last thing people need is additional stress around end-of-life decisions.

“When you’re grieving so hard, you don’t have brain cells left to deal with this,” Estes says. “Having been through it myself, and having been put completely through the ringer, I want to make sure this is an easier process to do. Not to say it’s the right choice for everyone, it’s just our choice.” ♦

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!