Taiwanese people living in the United States face a dilemma when loved ones die. Many families worry that they might not be able to carry out proper rituals in their new homeland.

As a biracial Taiwanese-American archaeologist living in Idaho and studying in Taiwan, I am discovering the many faces of Taiwan’s blended cultural heritage drawn from the mix of peoples that have inhabited the island over millennia.

Indigenous tribes have lived on the island for 6,000 years, practicing their diverse ancient traditions into the modern day. Chinese sailor-farmers arrived during the Ming Dynasty 350 years ago. The Japanese won a naval battle with China and governed Taiwan as a colony from 1895 to 1945. Today, Taiwan is a vibrant democracy, albeit with contested sovereign status. Peoples from every corner of the planet visit, work and live in Taiwan.

Language, religion and food from all these traditions can be encountered in the cities and villages of Taiwan today. Multiple beliefs and customs also contribute to the rituals Taiwanese people conduct to send family members into the afterlife.

Death rituals

Taiwan’s death rituals offer a bridge with the afterlife that stems from multiple spiritual sources. Buddhists, who make up 35% of Taiwan’s population, believe in multiple lives. Through faith and devotion to Buddha and the accumulation of good deeds a person can be freed from the cycle of reincarnation to achieve nirvana or a state of perfect enlightenment.

This belief is fused with elements of the island’s other belief systems including Taoism, Indigenous spirituality and Christianity. Together, they form death customs that showcase Taiwan’s multiculturalism.

In the streets of Taiwan’s metropolises and villages alike, temples, churches and wooden ancestor carvings invite one to contemplate eternity while the odors of nearby food vendors – such as stinky tofu, a local delicacy – tempt people to pause and enjoy earthly delights afterward.

The rituals associated with passing from this life include cemetery burial or traditional cremation practices. The dead are cremated and placed in special urns in Buddhist temples.

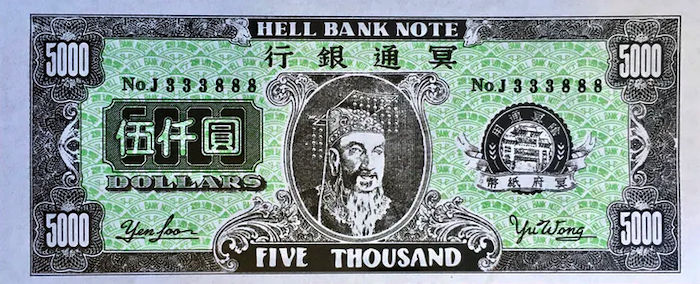

Another rite involves burning of what are known as “hell bank notes.” These are specially printed non-legal tender bills that may range from US$10,000 to several billions.

On one side of these notes is an image of the Jade Emperor, the presiding monarch of heaven in Taoism. These bills can be obtained in any temple or even 7-Eleven in Taiwan. The belief is that the spirits of ancestor might return to complain if not given sufficient spending money for the afterlife.

Adapting in America

My Indigenous great-great-grandmother married a Chinese man and her great-grandson – my father – grew up speaking a typical blend of languages for the 1950s: the local dialect, Hokkien, as well as Japanese, Cantonese and Mandarin. Arriving in the U.S. at the age of 23 to study electrical engineering, my father mastered English quickly, married my Euro-American mother, and raised a family in the American West.

Taiwanese people living in America often cannot participate in the rites of mourning and passage conducted back home because they do not have time or money, or recently, pandemic related travel restrictions. So Taiwanese Americans adapt to – and sometimes, accept the loss of – these traditions.

When my Taiwanese grandmother, whom we affectionately called Amah, passed away in 1987, my father was unable to return home for the Buddhist ritual organized by his family. Instead, he adapted the “Tou Qi,” pronounced “tow chee” – usually conducted on the seventh day after death.

In this ritual, it is believed that the spirit of the recently deceased revisits the family for one final farewell.

My father adapted the ritual to a modern U.S. suburban home: He filled our dining room with fruits and cakes, as my Amah was a strict Buddhist vegetarian and enjoyed eating cakes. He put pots of golden chrysanthemums on the table and incense whose smoke is believed to carry one’s thoughts and feelings to the gods.

He then opened every door, window and drawer in our house, as well as car doors, and the tool shed to ensure that our grandmother’s spirit could visit and enjoy the food with us for the last time. He then settled in for an all-night vigil.

After helping Dad with preparations, I returned to my small apartment across town, placed flowers and fruit and a candle on the kitchen table, opened the windows and doors and sat through long dark hours of my own small vigil.

I reflected upon the memory of my grandmother: a petite woman who raised six children during World War II by hiding in the mountains and teaching them to forage for snails, rats and wild yams. Her children survived, got educated, and traveled the world. Her American grandchildren learned how to stir fry in her battle-scarred wok, lugged all the way to the U.S. in a suitcase, and peeked curiously as she performed Buddhist prayers each morning in front of the smiling deity.

My vigil ended with the rising of the sun: the candle burnt out, the flowers drooped, and the fragrance of the incense faded. My grandmother, whose name in translation is “Fairy Spirit,” had eaten her fill, and said her goodbyes.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!