By Anna Gorman

Mary De Freze, who has heart problems, chronic lung disease and a history of falling, knows she may not have too many years left. And she’s clear about what she wants — and doesn’t want — at the end of her life.

“I don’t want to be in a lot of pain and I don’t want to be kept alive by machines,” said De Freze, 81.

After a recent fall landed De Freze in Stonebrook Healthcare Center with cracked ribs and a bruised spleen, the staff there helped her put those wishes on paper.

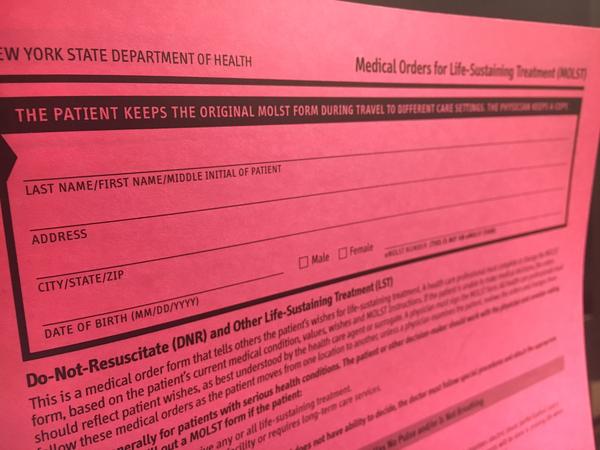

The document they used, Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment, or POLST, gives patients a choice of how much medical care they want in an emergency.

Prompted by a state law that took effect this year, a coalition of emergency and social service providers is working to create an electronic registry for POLST forms so they will be available to first responders and medical providers when they are needed. The group is starting with a three-year pilot project in San Diego and Contra Costa counties that could serve as a model for a single, statewide registry. Paper-based POLST forms are used across the nation, but electronic registries exist only in a few states, including Oregon, New York and West Virginia.

Many adults have advance directives, which are legal documents that designate a surrogate decision-maker and list patients’ health care preferences. POLST forms go further, creating a set of medical orders that are signed by the provider and the patient or a legally recognized decision-maker. Unlike advance directives, they are specifically designed for people who are already seriously ill or near the end of life.

Research shows that POLST forms help ensure patients’ end-of-life wishes are followed. But that only happens if doctors and other emergency providers can get them quickly. In California, the POLST form is a paper document and might not be at hand when patients need it. In many situations — a heart attack, a stroke or severe dementia — patients may not be able to communicate. And doctors may not be able to reach their families right away.

FOLLOWING WISHES

Without information on what patients want, there is an increased chance their wishes won’t be followed.

“If you take the time to fill out a POLST form, you want your health care wishes to be known and respected,” said Kate O’Malley, a senior program officer at the California Health Care Foundation, which is funding the pilot project in California.

A POLST registry “would be a big plus for being able to give people the care they want and not give them the care they don’t want,” said Jeffrey Klingman, a neurologist at Kaiser Permanente in the East Bay.

“I don’t want to do things to people they don’t want done,” he said. “On the other hand, I don’t want to delay treatment while I wait to figure out what they want done.”

Oregon was the first state to use POLST forms in 1991. California has been using them for nearly 20 years. Filling out the forms is voluntary, but once they are completed and signed, they must be followed, and providers have immunity from criminal prosecution or civil liability when they do so in good faith. The forms are printed on bright pink paper and include decisions such as whether a patient should be resuscitated, admitted to the intensive care unit or have a feeding tube inserted.

Tony Chicotel, a staff attorney at California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform in San Francisco, said patients should document their wishes in advance but that there are some downsides to doing so only with POLST forms. They are not nearly as thorough as advance directives and don’t allow you to designate a decision-maker, he noted. “The most comprehensive health care planning you can do is to name an agent.”

In addition, Chicotel said many nursing home residents are being urged to complete POLST forms even if they aren’t seriously ill or at the end of life. He said if an electronic registry is created, it should also include advance health care directives.

California’s electronic registry would be a secure, cloud-based portal for medical providers to submit and view POLST forms, regardless of whether the patient was at home, in the hospital or at a nursing home.

A ‘NO BRAINER’

An electronic registry is a “no-brainer,” said Judy Thomas, CEO of the Coalition for Compassionate Care of California, which coordinates the state’s POLST program. But implementation will be much harder because it will require the cooperation of state agencies, doctors, emergency personnel, and private and public health systems. Success will also depend in part on hospitals’ willingness to share records.

“We are not asking all health systems to share all information,” said Allen Namath, co-founder of Vynca, the technology vendor for the project. “But the value in these forms is being able to share them.”

Patients who go through the trouble of documenting their medical preferences shouldn’t have to worry about getting the wrong care, he said. “It is not a cardiology problem. It is not a cancer problem. Helping improve our end-of-life care … applies to everybody.”

San Diego County already has a health information exchange that allows hospitals and health systems to share some data. But Contra Costa County is further behind.

“It’s going to be challenging,” said Donald Waters, executive director of the Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Association, which is helping lead the pilot project.

But Waters said it’s worth the effort to overcome the hurdles because having documents uploaded means paramedics and others will know in an instant if patients want to be resuscitated or just kept comfortable.

Situations arise every day in which being able to access POLST forms electronically could improve end-of-life care, said Tom Sugarman, an emergency physician at Sutter Delta Medical Center in Antioch.

“If you come [to the hospital] in full cardiac arrest … we only have one or two minutes to make a decision,” said Sugarman, who educates doctors about POLST. “All physicians are going to err on the side of preserving life.”

Sometimes, however, a patient may prefer comfort care, Sugarman said. A POLST form — if it is available — means families don’t have to make decisions during an emergency, he said. “The worst time to have that conversation is during a crisis.”

FORMS CLOSE BY

At Chaparral House, a nursing home in Berkeley, the POLST forms are in the residents’ folders at the nursing station. The forms go with patients to the hospital, but sometimes there is still a disconnect. Administrator KJ Page recalls one resident getting a feeding tube when he didn’t want one and another who almost underwent bypass surgery against his wishes.

Audrey de Jesus, 83, arrived at Chaparral House just a few months ago. She uses a wheelchair and an oxygen tank. Beside her bed sits a Bible and a book of Psalms.

De Jesus has seven children and said the form tells them exactly what she wants — comfort-focused treatment — so there aren’t any questions in an emergency. “I want pain control and the least suffering for my family,” she said.

Stonebrook Healthcare Center Social Services Director Shirley Jackson said filling out POLST forms is part of the admission process. “It’s almost like a driver’s license for the end of your life,” she said. “It’s important.”

Having the form available electronically would make it much easier for everyone. “If, God forbid, you have to send somebody out in an emergency, especially if they are unresponsive, it’s right there in the chart,” she said.

De Freze, a former certified nursing assistant, said she plans to put her pink form on her refrigerator when she leaves Stonebrook. She knows she could have an emergency and may not be able to tell doctors or paramedics what she wants.

“You can’t communicate if you are in excruciating pain,” she said.

Complete Article HERE!