[G]eraldine was warmly opinionated and, along with her husband, she’d raised her four daughters to be the same.

When work settled and time allowed, she melted into the couch next to any of her children who were home and turned on the Hallmark channel. If a movie showed people who couldn’t care for themselves, she would remark, “I don’t want to live like that,” or “if that’s me, don’t bother doing all that.”

On May 25, a clot blocked a blood vessel in Geraldine’s heart. Her husband performed CPR. She was whisked to the hospital, where her heart survived, but lack of oxygen launched her brain into uncontrollable seizures. At age 56, her melodic Irish accent was silenced.

Her lips sagged around a breathing tube when I met her three weeks later. Her limbs lay wherever we put them. Kinked gray hair stood in all directions from her scalp, pushed aside by electrodes that recorded brain activity.

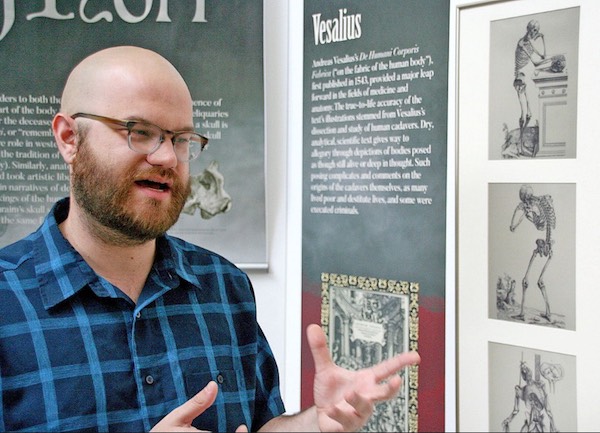

In the small conference room in our neuro intensive care unit, we discussed Geraldine’s prognosis with her family.

“We can place a long-term breathing tube in her neck and a feeding tube in her stomach,” I said, “but there are no cases in the medical literature of someone like her living independently again. The best we could hope for is a life of near-complete dependence.”

“When we first came to the hospital, doctors told us my mom might be brain-dead,” one of Geraldine’s daughters countered. “Now, she takes breaths on her own sometimes. She’s already improving.”

Just as Geraldine was stubborn and exceptional in life, her family believed she would be exceptional in beating her prognosis.

“It might be different if my mom was 70 or 80,” her daughter went on, “but she’s only 56.”

For Geraldine’s family, the immediate fear of watching her die outweighed the unfamiliar pain of sustaining her on machines and watching her disappear in a long-term care facility.

Our medical team had seen hundreds of people like Geraldine, most of whom returned to the hospital month after month to manage complications of immobility. Sparse cases of recoveries were overwhelmed by painful, expensive, drawn-out deaths, ones we would never wish for ourselves or our own families.

But for Geraldine’s family, every decision was new. For them, nobody was like Geraldine.

In every other part of medicine, doctors make recommendations for medications, lifestyle changes and surgeries. We don’t offer cancer patients six different chemotherapy regimens and ask them to weigh the pros and cons. Yet when it comes to end-of-life decisions, doctors are terrified of violating patient autonomy. We are scared of our own medical opinions.

Instead of saying, “I recommend…,” we often offer a platter of life-prolonging measures, most of which are unlikely to improve a patient’s quality of life, but which offer the possibility of hope. The patient’s heart will still beat. Her personality will be gone, but her chest will still rise and collapse. Families see an opportunity for loss to be delayed, perhaps even dodged. Then we are surprised when they take us up on the offer to prolong dying.

“I think she would want more time to try and recover,” Geraldine’s daughter said.

So we kept Geraldine alive. A plastic breathing tube sprouted from her neck and a feeding tube with peach-colored formula buried itself in her stomach.

In the hospital, Geraldine’s family learned the common complications of immobility: infection, blood clots and bedsores.

When the infection started, a fever sounded the alarm. We counted the possible causes. Geraldine had a breathing tube in her windpipe, a feeding tube in her stomach and an IV line in her neck, each an access road for bacteria. Lying in bed put her at risk for pneumonia and urinary tract infections. Like mosquitoes in standing water, infections proliferate when the body is still.

Geraldine’s blood clots weren’t a surprise. Medical students are inculcated with the famous triad of conditions that predispose patients to clots, and Geraldine had all of them. Her body was inflamed and torn from the heart attack, infections and procedures that caused her blood vessels to release molecules that helped blood to clot. Lying in a hospital bed, not moving anything unless it was moved, her circulation slowed. Pools of static blood dried into a thick paste in her blood vessels.

Thanks to aggressive nursing care, when Geraldine developed a bedsore it was managed at an early stage. But the term “bedsore” is an understated euphemism. It recalls the annoyance of a cold sore or the tenderness of muscles after the gym. The grotesque image of bone pressing through skin is hidden.

In people who are immobilized, bedsores develop under bony prominences like the heels and the skull. At first, the skin becomes red. If the bedsore progresses, the skin’s outer layer, then the inner layer, breaks down. Finally, in the most severe stage, bone, muscles and tendons are exposed. The entire process can happen in just a few days.

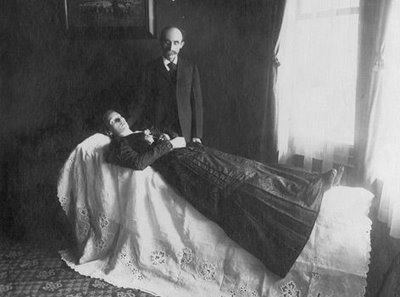

Sixty days after her heart attack, Geraldine was stable enough to leave the I.C.U. She was in a persistent vegetative state — unresponsive to external stimuli. She opened her eyes, as if she were about to say something, but nothing ever came out. Her gaze roved around the room. An ambulance took her to a long term care facility, where she was dependent on machines and people.

“When you first hear someone you love is sick, you think it’s a short term thing,” her daughter told me over the phone a month later. “It’s adjusting to the long term aspect that’s hard.” Geraldine’s daughter woke up at 5 a.m. every day to spend time with her mom before work.

“I think it’s more of a disappointment for my dad,” she said. “He told us that if he ever gets sick, he doesn’t want any of this.”

Geraldine’s family lived between hope and guilt, with the weight of each side in flux. “If my mom knew what we were doing right now, she’d probably be mad at us,” her daughter reflected a few weeks ago.

Yet in the same breath, her voice rose and she said: “My mom’s a fighter, so I think she would be happy with us giving her a shot. We’re hoping for this miraculous turnaround.”

It did not come. Geraldine died of sepsis earlier this month, after more than four months of care.

“People don’t know what they’re in for,” Geraldine’s daughter reflected after the funeral. “It hurt all of us to see her like that.”

In the final days of Geraldine’s life, a doctor asked if the family of another patient in the I.C.U. could visit Geraldine to see what prolonged dying looked like. Geraldine’s family was kind enough to agree.

The visiting family chose to transition their loved one to hospice care.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!