A palliative care nurse explains what to expect in the last days and hours.

Excerpted from Advice for Future Corpses by Sallie Tisdale.

In Advice for Future Corpses, author and palliative care nurse Sallie Tisdale shares insight and contemplation into what constitutes a good death. Managing our own avoidance and fear, she writes, is key to shepherding a peaceful final passage. Here she describes what to expect, and consider, during the last days and hours.

Death takes many forms. One death is anticipated over months. Another death is stunningly abrupt. And now and then death is held back by technology. I have seen how these deaths are different, and they are all the same, in the end: A person breathes and then breathes no more. He enters a stillness like no other. Breath. Another breath, and then no more. But when the breaths are made by a machine or the blood pressure is sustained by powerful drugs, someone has to make an awful decision.

Many aspects of medical and nursing care become unnecessary or intrusive for a dying person. Will the result of a lab test change the plan? If not, then don’t do it. Why take another vitamin? Are you really worried about the cholesterol level at this point? You don’t need to check blood pressure routinely. But sometimes a person is already hooked up—intravenous fluids and drugs to raise blood pressure and support for breathing—and the only way to stop the intrusion is to unhook. The advent of machines like defibrillators and ventilators created a new kind of crisis for the dying. (One report from the time referred to “this era of resuscitatory arrogance.”) A lecture in 1967 about how medicine should define death was called “The Right to Be Let Alone.”

Futility is a legal term in health care. A doctor, a team of people, even a hospital, can invoke futility and refuse to continue treatment that only prolongs suffering. This doesn’t happen immediately; it’s a drawn-out, painful process. The vocabulary makes everything worse. Doctors speak almost glibly about “withdrawing” or “withholding” treatment. The nurse says, “There’s nothing more to be done.” Which is a stupid thing to say, because there are all kinds of things to be done; they just don’t involve trying to keep someone alive. Such comments create a terrible sense of culpability in a heartbroken spouse or child. But what is really being done is good care.

Journalist and author Virginia Morris pleads for a change of terms: “When we take a terminally ill patient off life support, we are not ‘pulling the plug,’ we are ‘freeing’ the patient to die. We are ‘releasing’ her from excessive technology and invasive treatments. When we allow death to happen, we are not killing people, we are caring for them. We are loving them.”

We want to put it off as long as possible. Even if we are sure that Mom or Dad wouldn’t want to be kept alive “on a machine,” in the moment of crisis when everyone is yelling at us to decide, we’re not prepared. We literally have no experience making such a decision; we may do it only once in our lives.

The hardest part is the loss, but a close second is the need to shove your own fears and desires to the side. Surgeon and bioethicist Sherwin Nuland said that at the time when decisions about life support and life-prolonging treatments are being made, “everybody becomes enormously selfish.” He emphatically includes doctors and nurses in with the family. We may not recognize that selfishness is driving the words we choose or the kind of advice that’s given. Doctors may not have any idea they are doing this. When they offer yet another experimental drug, they may genuinely believe they know what’s best for the patient. But best: Best is subjective. Best is your point of view. Best is what you want.

Being able to make a decision like this for another requires an understanding of each other, and time for self-reflection. You have to consider the painful, scary, and unwanted fact of separation. You are the proxy for the person in the bed. What she wants is all that counts. You want the person to live. Or you want the person to die your version of a “good” death. Or you want him to live another week until the rest of the family arrives. You want the gasping holler of pain in your chest to go away. Can you choose a course of treatment that will allow the person you love most in the world to die? Can you say no on their behalf to something you would choose for yourself? Can you say yes on their behalf to an end you would never want? Can you set your own beliefs to the side? This inevitable conflict of interest—you are dying and I want you to live—is why a spouse or close family member often should not be the one making all the decisions. You have to ignore the begging chorus in your head, because it’s not about what you want.

In an old Japanese tradition, a person writes a poem on New Year’s Eve that will be read at their funeral if they die in the coming year. A modern addition to this practice includes having a professional funeral photograph taken and picking out the clothing you want to wear, in styles specially made for corpses. The Japanese word jōjū means ever-present or unchanging. I like the translation “everlasting.” The image of jōjū is often the moon. How can the moon, which is never the same from night to night, be everlasting? And yet it is always the same moon. Jōjū is that quality of unstoppable change and the eternal at once. Death comes even while we are alive.

In the early 1700s, Mizuta Masahide, an admirer of the great poet Bashō and a doctor by profession, had a fire at his home. It burned down his storehouse, leaving his family impoverished. His poem that year:

My storehouse burned down.

Now nothing stands between me

And the moon above.

Everlasting.

A dying person’s attention turns toward a place we do not see and that they cannot explain. They are done with the business of the living, as it were, and more or less finished with us. Now they are not a mother or a plumber or a friend. Now they are entirely a dying person, and the world begins to shine. In spite of going hours without speaking, in spite of needing help to button a shirt, he is busy. He may not have the energy to talk, because he is waiting for something and that takes everything he has left.

He may be waiting to understand why.

Laugh. Laugh! Sing. The last kiss, the last dream, the last joke to tell. I have been telling you all the many things we might say, and shouldn’t. Things to say as the end is coming: I love you. I hope the best for you. We will be all right. Go with peace.

Then we are listening again. We are returning to stillness, and to hearing what is being said without words. Most of us are not used to silence. It takes getting used to. The background noise of our lives is near-constant: endless voices, television, music, traffic, the ping from incoming texts, the demanding requests of daily life. Because we aren’t used to silence, we don’t understand how to be in it, how full it is. We may struggle against it, but silence is part of this world now. Silence is attention. Attention on this, right here, right now. Attention on the hand against the sheet, the texture of the cotton, the cool cotton. The hand rising to take a cup; the hard, warm curve of the cup. The steam. The heat. The sensation of the bending tendon in the hand, the scratch of a nail along the bedcover. Inhalation. Exhalation. All this in silence, filled with the music between words, what you might call the music of the spheres—the world’s hum. The faint vibration of breath and muscle and time.

The writer Dennis Potter died of pancreatic cancer. A few months before his death, he gave a remarkable interview on the BBC. His wife was also dying, of breast cancer, and he was her main caregiver. He was relaxed and smiling—his pain cocktail was a combination of morphine, champagne, and cigarettes—and full of his signature dark humor. Dying, he said, gave him a new perspective on life; it gave him a way to celebrate.

“The blossom is out in full now,” he said, describing what he saw from his office window. “It’s a plum tree, it looks like apple blossom but it’s white, and looking at it, instead of saying, ‘Oh, that’s a nice blossom’… last week looking at it through the window when I’m writing, I see it is the whitest, frothiest, blossomiest blossom that there ever could be, and I can see it. Things are both more trivial than they ever were, and more important than they ever were, and the difference between the trivial and the important doesn’t seem to matter. But the nowness of everything is absolutely wondrous.” He couldn’t really explain, he added; you have to experience it. “The glory of it, if you like, the comfort of it, the reassurance … not that I’m interested in reassuring people, bugger that. The fact is, if you see the present tense, boy do you see it! And boy can you celebrate it.”

He died nine days after his wife.

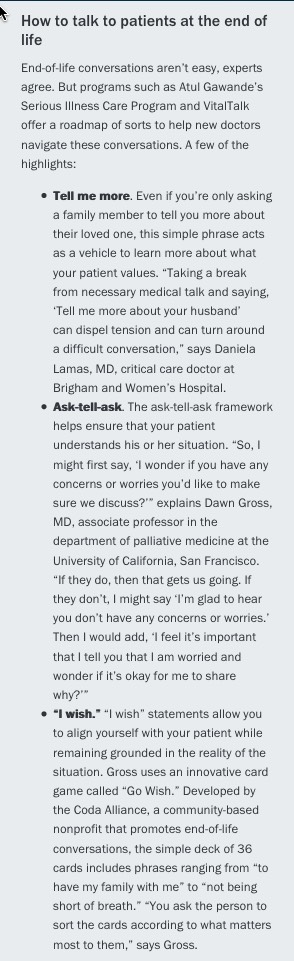

accredits medical schools, does not require clinical rotations or courses on palliative medicine or end-of-life care. Part of the issue is that these skills “can’t be taught through lectures and demonstrations,” says Susan Block, MD, a professor of psychiatry and medicine at Harvard Medical School. “The only way to improve competencies is through field practice and feedback.”

accredits medical schools, does not require clinical rotations or courses on palliative medicine or end-of-life care. Part of the issue is that these skills “can’t be taught through lectures and demonstrations,” says Susan Block, MD, a professor of psychiatry and medicine at Harvard Medical School. “The only way to improve competencies is through field practice and feedback.”