His readers gave him an outpouring of sympathy.

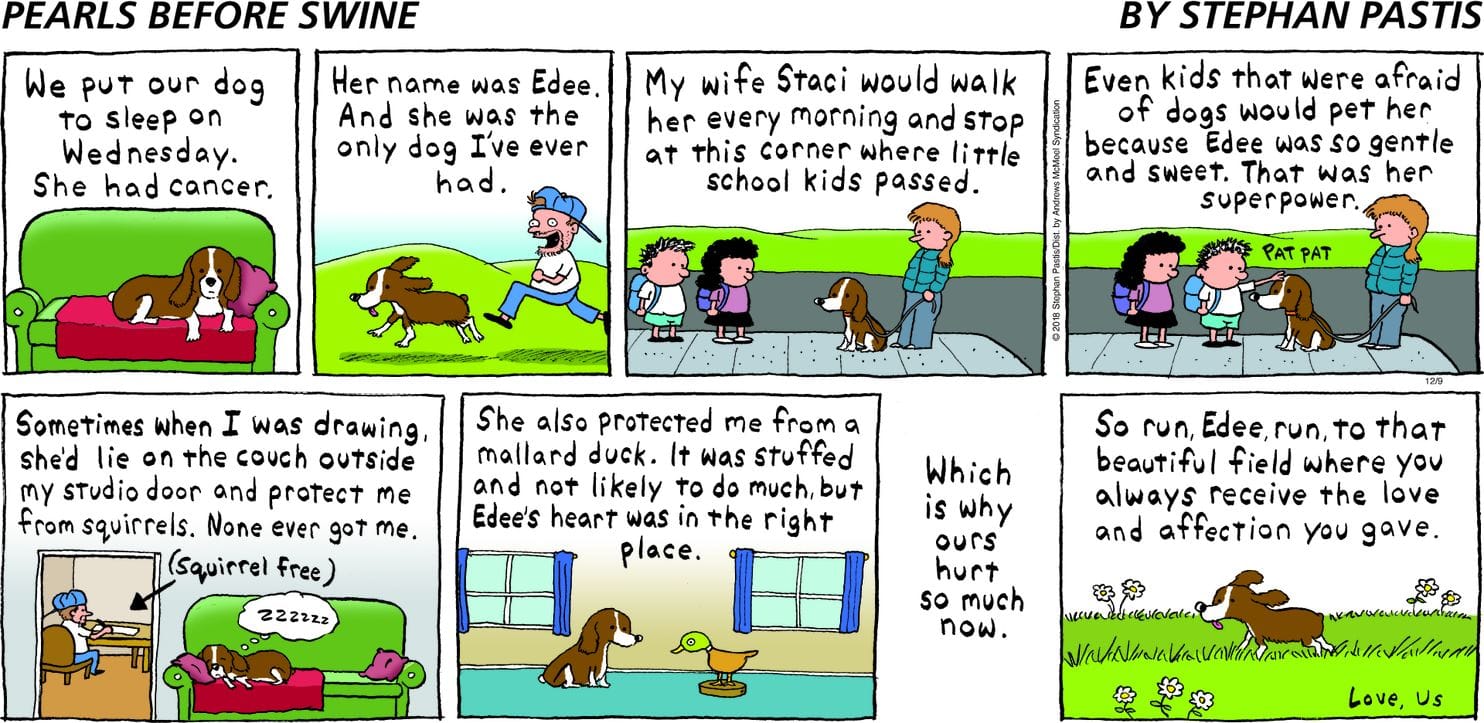

Stephan Pastis ducked into an Arizona coffeehouse last September and began to grieve. He sketched and cried as he wrote the words, “We put our dog to sleep on Wednesday.” The plot twist was, about 800 miles away, Pastis’s dog was still alive, though her time drew near.

Edee, a loving and gentle springer spaniel, was the only dog Pastis had ever had. Now here he was, a cartoonist who uses drawing as a coping technique, on a personal trip far from his Northern California home, unable to comfort Edee and say goodbye to her one last time before she was put down.

The resulting art was not the sort of sentiment that readers usually expect from Pastis, a former lawyer. As the creator of the popular comic “Pearls Before Swine,” he entertains millions of fans by often trafficking in darker and snarkier human emotions, as channeled through a gallery of animal characters, including the self-serving Rat and the wide-eyed innocent Pig.

Although some comic-strip creators draw upon events from their personal lives for inspiration, most cartoonists don’t share their experiences directly through their work, free of fictive elements or filtering techniques. But on that emotional day in Phoenix — where Pastis was visiting his father, who has Alzheimer’s disease — the cartoonist decided to get as directly personal as an artist can get. “I’ve always run to my creativity to cope with life,” Pastis says.

So he wrote that Edee had cancer. He wrote that she was so sweet that “even kids that were afraid of dogs would pet her.” He wrote that she would “protect” him from squirrels and a stuffed mallard duck while he worked in his Santa Rosa studio. And he wrote of the “hurt” in the hearts of his family, including his wife, their 21-year-old son and 17-year-old daughter.

The punchline-free purity of that comic strip, published in December, struck a chord. Hundreds of readers contacted Pastis. And this week, his syndicate, Kansas City-based Andrews McMeel, announced that the Edee strip was its most buzzed-about comic of 2018, with nearly 500 comments and almost 1,200 “likes.”

That speaks, his syndicate says, to the power of going personal.

“It connects the readers to the comic at a whole different level,” says John Glynn, president and editorial director of Andrews McMeel Syndication. “It can, however, be jarring if the audience isn’t used to it.

“Stephan has done it well and regularly enough over the years,” Glynn continues, “that his readers know that they see a version of the cartoonist that you don’t see in most comics.”

A recurring character in “Pearls Before Swine” is an avatar of Pastis, comedically depicted as a beer-bellied, stubble-faced, overambitious and pun-happy hack whose work is insulted by the very characters he has created. But on occasion, Pastis the avatar will share an honest, true-life slice of himself.

When those genuine ideas come, Pastis says, he typically tries to draw them, even if he ultimately doesn’t publish them — because he doesn’t want to gum up the creative flow.

“When I sit down to write,” he says, “what’s there is there. When something tragic has happened” — from the death of a relative, say, to the enormity of a terrorist act — “the ideas seem to have a narrow spigot, and what’s there is something you have to get out — you have to write it.”

Last September, though, Pastis was feeling especially emotional. He had just come from being on set for a Disney film adaptation of his kids’ book series, “Timmy Failure.” Now here he was in Phoenix, where his father did not recognize him, and then his wife called to say that Edee would need to be put to sleep within hours to minimize the pet’s suffering — much sooner than they had expected.

“I was all by myself out there,” he says.

The cartoonist walked to the Lux Central cafe, pulled his ball cap down low and got lost in his art, listening to such mournful music as “To Build a Home” by the Cinematic Orchestra. He was trying to communicate through pictures both his love for his pet — he never had a dog as a boy and had come to fear dogs after once being bitten — and the degree to which Edee had become a part of the family over six years.

Edee was due to be put down at 11 a.m. Pastis finished drawing and headed to the Phoenix Art Museum — where he gazed at Frida Kahlo’s 1938 painting, “The Suicide of Dorothy Hale” — before calling his wife to hear how Edee’s final moments went.

Pastis had touched many readers in 2003, when he created a heart-wrenching comic after watching a news report about a bus attack in Jerusalem that killed six children. And the cartoonist got especially personal in 2012 when a poignant “Pearls” strip eulogized his father-in-law.

For Edee, Pastis let that creative spigot again flow.

“Sometimes when you write from the heart, in a moment like that, it has a way of distilling the essence of what is in you in a very straight, direct way,” Pastis says. “What comes out is sometimes pretty meaningful.”

When the strip ran Dec. 9, the immediate response was strong and uncommonly large, the cartoonist says. Many of the readers who contacted him had recently lost their pets.

Wrote one commenter on the syndicate’s GoComics.com site: “Your comic is really hard to read. I can tell because my eyes are starting to sweat.” Some readers offered thanks and condolences and spoke of a pet’s afterlife across “the Rainbow Bridge.” Another commenter said: “Sometimes the best comics are the sad ones.”

A comic strip like that, Pastis says, “provides a sort of release of emotion — it becomes this thing they can connect to.”

And comics have the ability, he continues, “to comment on your life in a way that helps you and the people around you.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

In front of them stood Sally Kaplan, one of three facilitators present from the organization

In front of them stood Sally Kaplan, one of three facilitators present from the organization

The object: to turn death from a feared end to something that is part of life.

The object: to turn death from a feared end to something that is part of life.

Do: Offer the opportunity for everyone to speak but allow those who want to remain silent to do so.

Do: Offer the opportunity for everyone to speak but allow those who want to remain silent to do so.  Death doulas

Death doulas Shatzi Weisberger, an 88-year-old retired nurse from New York City is a regular, too.

Shatzi Weisberger, an 88-year-old retired nurse from New York City is a regular, too.