Solace in a trying time

Part 3 of 3

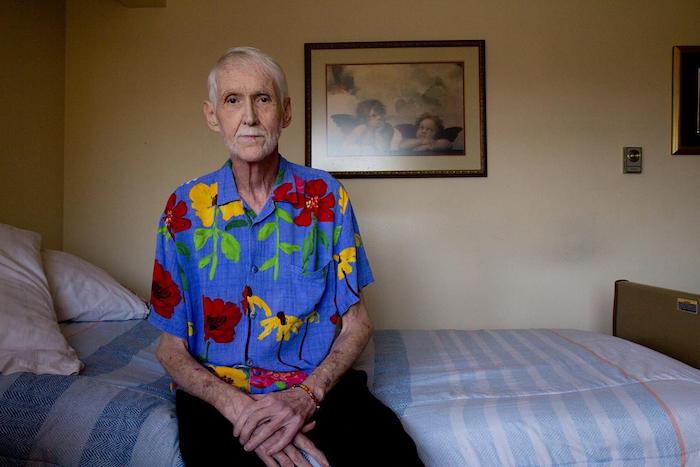

As Robert Fuller lay dying, he knew he was not alone.

His husband, Reese, stood by his head, crying into a pink towel. They’d been married that morning. A soprano sang over the mezzo piano melody of a violin, soft, but enough to fill the small, crowded room. Those closest to him laid their hands on his arms, torso, thighs and shins.

Downstairs, in the common room of Primeau Place, the affordable housing complex in which Fuller lived, the atmosphere was jovial, full of memories, food and music.

But later, in the bedroom as Fuller’s eyes closed, the gravity of the moment was palpable — to be there was an honor beyond grief.

Perhaps a few people in the room had watched a person die. It seems unlikely any had ever received an Evite to a combination wedding/death-day themed with Hawaiian shirts, courtesy of the host. But there’s a first for everything.

There are those by profession or by predilection who choose to stay with the dying until the dying is done, to comfort the loved ones left behind and ease the souls of the deceased into whatever comes next. They sit in calm vigil so that others, like Robert Fuller, need not be alone.

These are their stories.

Nancy Rebecca

At 10:30 the morning of Robert Fuller’s death, Nancy Rebecca joined Fuller and Reese Baxter in marriage.

She anointed them with nag champa oil, rubbing the scent of magnolia and sandalwood into their hands and asked each to take the other in lawful and spiritual marriage. They obliged.

For nine and a half hours, the two were wed. And then, at roughly 8 p.m., Fuller exhaled his final breath.

To Rebecca’s eyes, it wasn’t the end of Robert Fuller. This was simply a new beginning.

Rebecca isn’t just a marriage officiant. That happy task was more of a favor than a calling.

Rebecca is a healer of conventional and unconventional methods. She practiced as a hospice nurse for eight years, caring for people as they groped blindly toward the eventual conclusion of life. That work takes a toll on the living as well as the dying. In 1994, she bought a book on meditation and gave the calming practice a try.

Everything changed.

“I went to bed and I had a spontaneous out of body experience,” Rebecca said. “When my spirit came back to my body I could see energy fields and I could see spirits.”

Initially, Rebecca found the experience overwhelming, she said. After all, she was a registered nurse, trained in Western medicine. Seeing spirits and energy fields simply wasn’t done.

“In some ways, the energy fields I see around people are quite beautiful. That is not what was disturbing me,” Rebecca said. “It didn’t fit with what I thought to be the truth.”

Rebecca decided to consult professionals.

Rebecca’s mother was a psychiatrist, her father a medical doctor. Afraid of going to an outside physician with her concerns, Rebecca went to her parents. Her mother reassured her.

“There’s nothing wrong with you,” her mother said.

It took time to process her new, perceptive abilities, to parse what and who she was seeing. But it afforded her the capacity to stay with people under her care, observing the angels that came to visit them and helping them understand their own brief glimpses into the beyond at the end of their lives.

Rebecca works mostly with the living these days, helping them to heal their bodies by righting their energies through meditative practice. However, her wife had known Fuller for years, and although he didn’t feel that he needed her healing talents, the pair did have discussions about what came next.

One day, she asked him what he thought the afterlife would be like.

“He said, ‘Well it’s a realm of judgment and grace. For me I hope it leans a little more toward grace,’” Rebecca recalled.

“I said, ‘Based on my experience, it does,’” Rebecca said.

Sile Harriss

The harp in Sile Harriss’ apartment is roughly 22 pounds and rises to the level of her chest when she stands next to it. The burnished gold of the maple wood glows in the low light — though she’s had it for decades, the instrument looks as though it was purchased the day before.

It’s small for a harp, Harriss said. It’s a Celtic harp, not an orchestral version, meaning it lacks pedals and has fewer strings, a deficit made up for in part by small levers at the top of each string that allow her to adjust the note produced by a half step.

That’s OK, though. She could hardly bring a larger instrument into hospital rooms.

For nearly 20 years, Harriss worked as a music-thanatologist, employing ancient melodies and lyrics to respond to the needs of the dying and their families. It’s a unique profession — Harriss estimates there are only 100 of her colleagues in the United States.

Music-thanatology is more than beautiful music, Harriss said. It’s about using the cadences and meters of musical traditions from the Middle Ages to support people through the process of dying.

“Actively dying can be hard work,” Harriss said. “We’re using the music as support, able to observe and discern the sense in the room.”

While there is a repertoire of music, every session is individualized to the needs of the patient and their families. Music-thanatologists react to the breath of the patient, their heart rhythms pumping through the monitors and to the emotions of those watching them go.

Metered, comfortable lullabies might give way to unmetered plain chant as the body systems fail and the vitals weaken, requiring a piece with less structure. Some sessions involved a single phrase or bars of music used repetitively. Sometimes, relatives would request a loved one’s favorite song, or need care themselves.

If family dynamics got tense as the end neared, it was Harriss’ duty to tend to their unspoken emotional needs.

“The work at that time is to work with the family before I get to grandma,” Harriss said. “They need to let go what their hopes have been.”

Harriss trained at the Chalice of Repose, a school located near Missoula, Montana. She found herself looking for a new purpose after her marriage of 30 years ended, and a friend mentioned the school. The idea captured her, and she began preparing to move from Seattle before she was even accepted.

“The letter came 10 days before school started,” Harriss said.

Harriss would spend two years training with 14 classmates, memorizing the repertoire, learning Latin and ultimately signing on as harp faculty. When she began craving life in the city again, she moved to Portland and was hired at Providence Portland Medical Center. If her beeper went off, even in the wee hours of the morning, she would take her harp in its case, go to the bedside and begin to play.

Over time, Harriss developed neuropathy in her left hand — she can no longer feel the strings underneath her fingers and plays the harp through muscle memory. Still, the music emanating from her instrument is warm and calming.

“I’m just in awe and grateful for the opportunity to have been with people this way,” Harriss said.

Arline Hinckley

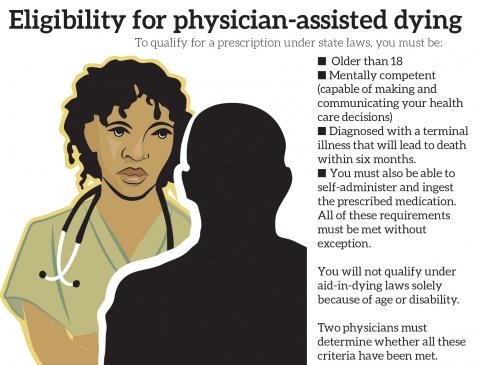

Arline Hinckley believes in doctors and medicine. She also believes in the right to die.

“We have a wonderful medical care system. It can work miracles,” Hinckley said. “Unfortunately, the tendency with all of this great medical care is to continue to treat people even when it isn’t going to benefit them.”

Hinckley is a board member and volunteer with End of Life Washington, the organization that helps patients like Fuller navigate the complicated road to dying with dignity. In the book “Extreme Measures: Finding a Better Path to the End of Life” by Dr. Jessica Zitter, Zitter compares the medical community’s response to terminal illness as a “conveyor belt,” Hinckley said.

“If you are very ill and get put on a respirator, that’s one way to get on the conveyor belt,” she said. “Artificial food and hydration is another way to get on it. Aggressive chemotherapy, and that kind of thing.

“Once you get on that conveyor belt, it is hard to get off. It is hard to say, ‘This is not what I want, please let me die,’” Hinckley continued.

Her experience in an oncology department after she graduated college convinced Hinckley that people needed a legal right to get off that conveyor belt. She saw many people die, sometimes horribly — the treatment was worse than the disease, she said.

Hinckley worked to get the Death with Dignity initiative on the ballot in Washington, more than a decade after the first of such laws passed in Oregon. She helped educate people on what it meant, and found that even those who did not want to use the law themselves saw value in affording others the opportunity.

She has also assisted people through the process herself.

“People are so full of grace and bravery at that time. They’re very determined,” Hinckley said. “The medication tastes terrible and some people have difficulty swallowing it, but I’ve seen 85-year-old, 95-pound ladies just chug that stuff. They’ve made up their mind, taken care of unfinished business, mended fences, come to a spot religiously where they feel this is OK. They’re just ready.”

End of Life Washington volunteers stay after the person has fallen asleep to help family and friends with the passing. The process can be healing for the living as well — the planning of the death allows people to come to terms with it more totally than a sudden loss, she said.

“They’ve done the work. So, of course they’re sad, but in some ways they’re relieved as well because the person they love is not going to be suffering any longer,” Hinckley said.

Only eight states allow people the option to take their own lives. The most recent law passed in New Jersey in March. Organizations like End of Life Washington are working to maintain the momentum so that everyone, regardless of their location, has an option at the end.

“People deserve a choice,” Hinckley said. “It’s not a choice everyone might make, but options are important to people.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!