Our aversion to the inevitable will only prolong our pain

by Emma Reilly

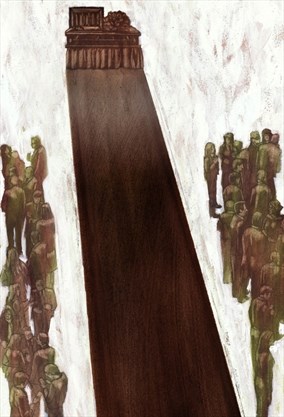

[D]eath lurks in the corners of our lives, threatening to emerge from the shadows at any moment.

When it bursts into our day-to-day existence — sometimes unexpectedly, occasionally anticipated — it is almost always unwelcome.

In Canada and the western world, we have reached a point where we will do almost anything to convince ourselves that death doesn’t exist.

“Death is the last great taboo,” writes Julia Samuel, a grief psychotherapist and founder patron of Child Bereavement UK, in her bestselling book “Grief Works.”

“We seem happy to talk about sex or failure, or to expose our deepest vulnerabilities, but on death we are silent,” she writes. “It is so frightening, even alien, for many of us that we cannot find the words to voice it.”

But experts who work in the field of death and dying say our increasing tendency to ignore death, no matter the cost, is hurting us.

Our death illiteracy means we are woefully unprepared to handle the growing number of aging people in our society, says Denise Marshall, associate professor of palliative care at McMaster University and the Medical Director of the Niagara West Palliative Care Team and McNally House Hospice.

According to Marshall, unless we begin to talk about death — to “befriend it,” as Samuel says — we will see suffering on a massive scale.

“This is like the perfect storm in North America,” said Marshall. “There will be too many people with too many needs, and not enough of us able to support them. We won’t know what to do with all of these dying people in frailty.”

Where did we go wrong?

When it comes to death and dying, where did we, as a society, start to go wrong?

First, Marshall says, it’s important to understand that our aversion to death is a uniquely postmodern, western phenomenon. While risks like communicable diseases or complications from childbirth used to bring death into our homes, in our modern society, death is something that happens far beyond the reality of our day-to-day life: in an impoverished or war-torn country, perhaps, or behind the closed doors of a hospital.

“At this very moment in other parts of the world, there is a huge death literacy — for often tragic reasons,” she said. “People are dying in famine, in war, in all kinds of things. The idea that death is a part of life, and it’s always there, has not been removed from the whole world.”

The tendency to eradicate death from our everyday lives is also a relatively new historical development, Marshall added. Just picture any death scene in a historical movie or novel; the dying person is likely to be at home, encircled by friends and family, rather than in a hospital surrounded by doctors. It has only been in the past hundred years or so that death became so highly medicalized.

Marshall dates the removal of family members from their loved ones’ deathbeds to the 1920s — the same time doctors started to better understand the infectious nature of tuberculosis.

“It’s the first time in the Western World that health care said, “You, the community, must stay out,”” said Marshall. “And so began the beginning of institutionalized death. It’s not that long of a history.”

Clare Freeman, the executive director of the Bob Kemp Hospice, sees families coping with death and dying every day. Residents only spend an average of 15 days at the hospice before they die, but Freeman says that some families are so wary of acknowledging death that they will avoid discussing it at all costs.

“Sometimes, residents will tell our staff things they feel afraid to tell their loved ones — such as, “I know I’m dying. They don’t think I am.””

“They don’t want to make their family sad,” added Trudy Cowan, the manager of events and community engagement at the Bob Kemp Hospice. “It becomes this elephant in the room.”

Freeman questions whether the declining role of religion in our lives may also be another factor in our denial of death. Most religions include rituals that mark the various stages of life, including birth, our entrance into adulthood, marriage, and death. Without these rituals, we may lose the touchstones in our lives that allow us to acknowledge these times of transition.

“The disconnection to faith in peoples’ lives has made us think, “Oh, we’ve escaped death,” Freeman said. “We’ve done a lot of things in society to remove ritual — to make it about individuality and choice — and that process of losing ritual is actually impeding our literacy about death and dying.”

Freeman argues that there is a cost to our death avoidance. She suggests that our society tends to put a timeline on grief, expecting family members to bounce back as quickly as possible after the death of a loved one. This turns a natural process — grieving — into a medical disorder.

“We somehow think that we’ve cured death. Then, since we’ve cured death, we’ve also cured mourning. So, if you’re sad or mourn beyond three days, we’re going to send you to a therapist. It becomes a clinical thing, whereas mourning and grief is a natural process,” Freeman said.

End-of-life care

For concrete strategies to help combat our society’s death-avoidance, Marshall points to the work of her mentor, Dr. Allan Kellehear.

Kellehear, a medical and public health sociologist, was the first to suggest that end-of-life care should be the responsibility of the entire community — not just medical professionals.

His groundbreaking 2005 book, “Compassionate Cities,” argues that workplaces, charitable organizations, clubs, churches, and community members should work alongside doctors and palliative care clinicians to care for the dying and bereaved.

The most effective way to foster this, says Marshall, is by “adopting a good old-fashioned public health approach.” Jurisdictions across Canada should invest in advertising, workshops, and awareness campaigns encouraging more conversation about death.

“We need for end-of-life care in Canada what we have done with smoking cessation. It’s a good analogy,” she said. “It takes time — this is a psychic shift.”

Many European countries are already using this approach.

In Ireland, coasters reading “Dying for a beer?” that described 10 ways to support a bereaved friend were distributed in pubs across the country as part of a public health campaign. In the United Kingdom, death education is part of the kindergarten curriculum.

Systemic changes like these are essential in order to handle the growing number of Canadians approaching the end of their lives, said Marshall. Currently, 70 per cent of deaths occur in hospital — and there’s simply not enough space in palliative care units, hospitals, and hospices to handle a major influx of the sick or dying.

In Canada, death rates continue to climb each year. Statistics Canada reports that the number of deaths across the country climbed from 654,240 between 2000 and 2002, to 722,835 between 2010 and 2012.

Unless our society learns to help care for the dying, Marshall says we will reach a crisis point where people will be abandoned at the end of their lives, left alone without medical or community support.

“Why is it a crisis? Because I don’t think we’ve fully grasped the fact that this isn’t going away. This is not a blip in society,” Marshall said. “We are living longer, with more complexities. One-hundred per cent of us, though, are going to be at end of life.”

Marshall points to China as an example of a jurisdiction facing a disproportionate number of dying people that completely outstrips the younger age group’s ability to care for them.

“That will eventually be us. It will be every country,” Marshall said. “What we’ll risk seeing is huge amounts of suffering in ways we haven’t seen before. True abandonment.”

Death education

In Hamilton, there are those who are already engaged in the type of grassroots advocacy that Marshall espouses.

Rochelle Martin is a community death-care educator. Her passion lies in supporting the dying and their families.

Martin, who lives in downtown Hamilton with her family, helps families with what she calls “home-based death-care.” She advises families who wish to have a home funeral about the practicalities of washing, dressing, and laying out the body of the person who has died.

Martin does not get paid for her work as a death-care educator, nor does she directly handle bodies (which would require her to have a funeral director’s license). Instead, she says she sees herself more as a “community renegade who whispers in peoples’ ears “you can do it.””

“I operate more like a lactation consultant — I can’t breastfeed your baby for you, but I can tell you how,” she said. “And I can really empower you to do it, because I think it’s so important.”

To earn an income, Martin, a registered nurse with a specialty in psychiatry and mental health, commutes to work at the Toronto General Hospital.

Her professional work as a nurse dovetails with her “renegade” work as a death educator. In fact, it was her experiences working in an emergency room supporting the families of people who have had sudden or tragic deaths that led her to begin her role in death education.

Martin noticed that family members have a natural disinclination to see their loved ones after they have died, especially if they have experienced trauma. But after a small amount of encouragement, however, most are able to have the closure of seeing their loved ones’ bodies.

“It was amazing and beautiful to watch. If they’re given even a tiny bit of encouragement or permission, people really know how to engage with death in a way that they initially thought they couldn’t or shouldn’t.”

There are those who think her work is strange, dangerous, unsafe, or possibly a health hazard — but she sees her work as an important tool to help our society become more comfortable with death. Unlike the traditional funeral industry, where our loved ones’ bodies are tended to behind closed doors (often at a cost of thousands of dollars), Martin says she acts as a gatekeeper who helps others deal with death in a practical, meaningful way.

“Any time anyone has the opportunity to engage with death like that, and finds out that it’s not scary, it’s not dangerous, it’s legal — every experience like that puts us further ahead.”

When the community becomes involved in a death, everyone benefits.

In October 2016, Monica Plant’s 91-year-old mother, Polly, suffered two strokes and fell twice in her home. By the end of that week, Polly, who still lived in her west-Hamilton home of 38 years, had been declared palliative.

Plant was relieved when her mother received permission to die at home, just as Polly had wanted. But for Plant, it created some logistical difficulties. The Community Care Access Centre provided her with three hours of care a day — which, as Plant says, “was something, but it left quite a few gaps.”

She had acted as her parents’ live-in caregiver for almost seven years and was deeply fatigued. She had already been through the emotional and daunting process of providing end-of-life care for her father, who had died at home the previous April.

Plant found herself at an emotional crossroads: she felt extremely grateful that her mother was allowed to live at home for the last few weeks of her life, but she was unsure about whether she could sustain the sort of round-the-clock care her mother needed.

What happened next is almost a textbook example of the kind of community involvement that Marshall says is so essential.

Plant reached out to her neighbours, her out-of-town siblings, and parishioners at Polly’s church. Plant’s neighbour went door-to-door along Undermount Avenue, asking residents if they would like to help ease Polly into her final weeks of life.

Within days, Plant’s support system grew to 25 households who would visit with Polly, do yardwork, bring meals, and providing Plant with some comfort and respite. Neighbours circulated emails containing meal plans and visiting schedules and swapped stories about how good it felt to come together as a community.

“(Polly) was somebody who liked things to happen organically, and that’s how it happened,” Plant said. She compares the effort to an urban-barn raising — a constructive, collective effort that allowed her mother to die in the comfort of her home.

The experiences enriched both Plant and her neighbours. As well as creating an interconnection between those who were involved in Polly’s care, it offered a glimpse of what we will all face at the end of our lives.

“What I think the byproduct of being able to die at home was that people on the street got to see what aging looks like. This is what happens at all the stages,” Plant said. “If you’re taken out when you’re retirement age and you go off to a retirement home, the neighbourhood doesn’t get a chance to see what happens when you age.”

Polly died at home on Nov. 30, 2016, in the arms of Plant and her twin brother — the way she had always wanted.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!