His body wrecked by ALS, my father insisted that his death, like his life, was his to control.

Ron Deprez with his daughter, Esmé, and son, Réal, in Maine in the late 1980s.

By Esmé Deprez

I was finishing up breakfast in New York when my dad sent me a text message. He was ready to die, and he needed me to help.

The request left me shaken, but that’s different than saying it came as a shock. I’d begun to grasp that something was really wrong 10 months before, in May 2019, when he’d come to California from Maine. He was there to meet his first granddaughter, Fern, to whom I’d recently given birth. But he couldn’t bend down to pick her up. He was having trouble walking, and he spoke of the future in uncharacteristically dark terms. We’d traveled to see him in Maine four times since then, and each time he’d looked older: his face more gaunt, his frame more frail.

At first, he’d walk the short distance to go to the bathroom. Then he needed someone to help him stand and use a portable urinal. Where once we’d all gather around the candlelit dinner table to eat, a ritual on which he’d always insisted, he now sat with a plate in front of the television. Eventually he started sleeping in a mechanical hospital bed on the first floor so he could avoid the stairs. He refused the wheelchair and walker, and kept falling as a result. I hated my growing hesitancy to place Fern in his lap, but sensed his fear of dropping her.

By the time my dad texted me, on March 12, 2020, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the incurable illness also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, had ravaged the 75-year-old body to which he’d so diligently tended—the body of a disciplined athlete and restless traveler who’d run 18 marathons, summited mountains across North America, and navigated remote stretches of Africa. It felt both cruel and kind that his “condition,” as he called it, spared his mind—the mind he’d used to become a Harvard-trained epidemiologist, preach the power of public policy, recite William Wordsworth from memory, and extemporize about Rousseau, Marx, and Krishnamurti. ALS had robbed him of his most prized ideals, independence and freedom, and trapped him in a brown leather recliner in his girlfriend’s living room. He was staring down quadriplegia. Ronald David Deprez had had enough.

I had come to New York with Fern and my husband, Alex. It was an absurd time to travel there: Coronavirus case numbers had begun to spike, and the city was shutting down, leaving the streets eerily empty. But I had work to do and plans to go see my dad afterward. I’d feared the pandemic might soon ground domestic air travel, stranding me across the country from him for who knew how long.

Maine had only recently legalized medical aid in dying, allowing people with terminal illnesses and a prognosis of six remaining months or less to obtain life-ending drugs via prescription. In April my dad became the second Mainer to make use of the new law.

He’d always said he’d sooner disappear into the woods with his Glock than end up on a ventilator or a feeding tube, alone in an institution. The law provided a more palatable path. Opponents call this method of dying, which is now legal in eight other states and Washington, D.C., physician-assisted suicide. Advocates prefer the term death with dignity. It’s an extreme act, not suited to most people. But it sits at the outer edge of a continuum of health-care options that allow people to retain control over how and when their lives might best end. And for the majority of Americans—who surveys show would, if faced with terminal illness, prefer to forgo aggressive interventions and die at home—more alternatives exist along that continuum than ever before.

The second-youngest of four children, my dad was raised primarily by his mother, who worked as a hotel chambermaid. After co-captaining his college football team, he went on to found a public-health research and consulting firm and a nonprofit. He became an amateur photographer, expert cook, and self-described Buddhist. He could wire a house, tile a floor, bag a duck, skin a deer, ride a motorcycle, and helm a boat. His life testified to the notion that if you work hard enough, you can do just about anything.

Then came ALS, a force he couldn’t bend to his will. The disease would cause his nerve cells to degenerate and die, turning his muscles to mush and depriving his brain of the ability to voluntarily control the movements involved in talking and swallowing. He’d lose his ability to walk and grow prone to choking, labored breathing, and pneumonia. He’d be dead within three years of the onset of symptoms, maybe five, after his body suffocated itself.

He wasn’t going to beat ALS. No one does. But neither was he willing to let it beat him.

Perhaps there’d been early indicators, easy to dismiss in the moment. While hiking with my husband in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains in 2013, Dad wobbled precariously on the boulder-strewn trails. During a trip he and I took to Beirut and Cairo in 2017, painful cramps wracked his legs in the night. That winter, walking across the parking lot after a day of skiing in the Sierra Nevada, a spill left him splayed out on the asphalt amid his gear.

Neurologists at Massachusetts General Hospital were the first to suggest ALS, in the summer of 2018. Dad refused to follow up as recommended, didn’t share the news for many months, and brushed it off when he did. Instead, he convinced himself and us that orthopedic surgeries would help him overcome what he cast as the typical fate of an aging athlete. But a knee replacement in September 2018 failed to improve his balance. Neck surgery in March 2019 didn’t halt the weakening and atrophying of his right arm, left him perpetually exhausted, and set in motion a downward spiral.

Back in the 1970s, when my dad embodied his progressive politics with a full head of curly brown hair and a bushy mustache, he helped craft health policy inside the halls of Maine’s statehouse. Decades later, within days of his neck surgery, lawmakers there proposed a radical shift in the state’s approach to life’s end: the Maine Death with Dignity Act. At least seven similar attempts since 1995 had failed. This one passed, by a single vote, making Maine the ninth state where assisted death is legal. (Oregon was the first, in 1994.) The timing proved propitious for my dad, its approval and implementation unfolding as he inched closer to needing it.

He was born in 1944, part of a generation that experienced waves of scientific progress and technological breakthroughs that have enabled people to overcome acute diseases and manage chronic conditions. These advances have allowed people to live longer, making those 65 and older a larger share of the population than at any point in history.

A health-care system designed to prolong life at whatever cost, however, often fails to let it end. “We’re giving people interventions they don’t want and treatments that are painful and make them lose control over their own destiny and well-being at end of life,” Laura Carstensen, who teaches psychology and public policy at Stanford and is the founding director of its Center on Longevity, told me. “And with Medicare costs soaring, we’re going broke along the way.” This last point is true not just as a matter of government budgets, but on the personal level as well. As Atul Gawande wrote in his 2014 book, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End, “More than half of the elderly in long-term care facilities run through their entire savings and have to go on government assistance—welfare—to be able to afford it.”

The pandemic has forced people to confront and consider death on a daily basis. Experts such as Carstensen say that’s not all bad: Conversations about dying and disease and end-of-life care can be uncomfortable, but research shows that they make it more likely for people to die in ways that honor their wishes, save money, and soften the heartache for those left behind.

The idea that patients should have a say in their own end-of-life medical care has been fought over for decades. Like many his age, my dad had signed a legal document spelling out his wishes that health-care providers withhold life-prolonging treatment such as artificial nutrition or hydration should he become irreversibly incapacitated. The first such document wasn’t proposed until 1967, and it would be decades before directives of that nature gained prominence and legal recognition nationwide. Only after Congress passed the Patient Self-Determination Act in 1990 were hospitals and other providers required to inform patients of their rights under State law to make decisions concerning their medical care, including the right to refuse treatment. That same year, in its first right-to-die case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a competent person has a constitutional right to refuse lifesaving hydration and nutrition. The court later decided that the Constitution doesn’t ensure the right to an assisted death, but it left states to make their own laws.

Assisted-dying laws go beyond the right to die passively by refusing food, water, and care. They allow people like my dad to proactively hasten the end. Some 71 million Americans, or 1 in 5, now live in states where assisted death is possible. While the number of people using the laws has grown over time, their ranks are still small: fewer than 4,500 cumulatively, according to data compiled by the advocacy group Death with Dignity National Center. In 2019, 405 died this way in California, the state with the highest number that year.

The broader principle of allowing people to control their final days has been shown to have clear benefits. It’s a top goal of palliative care, for example, a growing interdisciplinary approach that emphasizes discussions between seriously ill patients and their care providers about how to better manage their symptoms. Studies show it can result in less aggressive treatments, improved quality of life, and reduced spending. Hospice care, which begins after curative treatment stops and death is near, can also cut hospital use and costs.

Maine’s law requires navigating a maze of mandates and built-in delays intended to discourage all but the most motivated candidates. As the process dragged on longer than he’d anticipated, my dad grew increasingly pessimistic that he’d gain access to this option. So in a desperate attempt to reassure him he could die on his own terms, I found myself in the disturbing position of contemplating other ways to help him end his life.

Perhaps my husband and I could carry him and his gun down the hill behind his house and leave him? Or take his rowboat out into the ocean and push him overboard? Smother him with a pillow while he slept? I was willing to consider the emotional and potential legal burden that came with these options, but they also horrified me. A hospice nurse had left a “comfort pack” of drugs in the fridge that included a vial of morphine. I researched how much would likely cause an overdose—more than we had. I looked into something called voluntarily stopping eating and drinking, or VSED. It sounded like torture, and my dad thought so, too. I explored what it would take to transport him to Switzerland, the only country that allows easily accessible assisted death for nonresidents. That could have taken months to organize.

I later learned of popular how-to books such as Final Exit, by the founder of the modern American right-to-die movement, Derek Humphry. It became a No. 1 New York Times bestseller after it was published in 1991 and has been translated into 13 languages and sold 2 million copies worldwide. (“The book’s popularity is a clarion call, signaling that existing social and clinical practices do not give Americans the sense of control they desire,” a New York state task force wrote in a report after the book’s publication.) In 2004, Humphry co-founded a group called Final Exit Network. According to its newsletter, its volunteers “go anywhere in the country to be with people, at no charge, who desperately seek a peaceful way to die,” even those “who are not necessarily terminal, including those suffering from early dementia.”

Plotting ways to off my dad felt absurd. The assisted-death movement aims to save people from that predicament. Ludwig Minelli, the lawyer who founded the Swiss assisted-death organization Dignitas in 1998, saw himself as a crusader for “the very last human right.” Jack Kevorkian, who helped about 130 people die and was convicted of murder for one of those deaths, believed people should be able to choose to end their lives even if physical death isn’t as imminent as some U.S. state laws now require.

Aid-in-dying is legal in all or parts of nine countries, and a 10th, New Zealand, will make it legal in November. Belgium and the Netherlands take the most liberal approaches. There, assisted death is available to adults and minors faced with constant and unbearable suffering, be it physical or mental. People with dementia and nonterminal conditions, such as severe depression, can qualify. Most countries with assisted-dying laws allow for euthanasia, which is when a doctor physically administers the drugs, usually by injection. All U.S. states forbid euthanasia and require patients to ingest life-ending drugs on their own.

Most Americans support giving terminally ill individuals the choice to stop living. Gallup says solid majorities have done so since 1990 (ranging from 64% to 75%, up from 37% when it first polled on the issue in 1947). Majorities of all but one subgroup, those attending church weekly, are in favor, including Republicans and conservatives. Significantly, one-third of Americans who obtain prescriptions for lethal drugs don’t end up using them, which advocates say underscores how much comfort and peace people can find in just having the option.

In the U.S., opposition has come mainly from religious groups that consider assisted death akin to suicide—to a sin—and from disability-rights advocates, who warn of the potential for abuse, coercion, and discrimination. The American Medical Association, one of many health-professional groups that has also fought the legalization of aid-in-dying, argues that the practice is “fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer.”

The hospice and palliative-care fields might seem like natural allies of assisted death. But Amber Barnato, a physician and professor at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice who studies end-of-life decision-making, says mainstream medicine has only recently begun to recognize the power of palliative care, and some people in the field worry that participation in assisted deaths might curb its reach. Palliative and hospice care are already wrongly linked with “giving up,” she says, and practitioners are wary of anything that could further that misconception. Research shows, however, that the availability of palliative care hasn’t suffered in places that have legalized assisted dying. And while opponents of Oregon’s law warned it would lead to the legalization of euthanasia, that hasn’t happened either.

Critics would call my dad’s death a suicide. But he wanted to live. He was going to die from his illness, regardless of whether he used lethal drugs to hasten it. The word “suicide” never felt like it fit.

On March 15, Alex, Fern, and I flew from New York to Portland, where my mom and dad raised my older brother, Réal, and me following their split in the mid-1980s. My dad had been living just outside the city with his girlfriend for the past year as he declined. Having just spent five days in what was then the heart of the pandemic, we said a quick, socially distanced hello before making our way to isolate at my dad’s house on Deer Isle, a three-hour drive up Maine’s coast. My husband and I both came down with moderate Covid‑19 symptoms within days.

Over the next few weeks, my dad made the necessary requests for life-ending drugs from his primary-care doctor, Steven Edwards. (The law requires an oral request, then a second oral request and a written one at least 15 days later.) I sent him photos from the long walks I took in the woods along the water, Fern strapped to my chest. I could sense how happy it made him that we were enjoying the area and learning the idiosyncrasies of his house. We talked or FaceTimed every day. He told me his limbs felt heavy and hurt.

Much about the coronavirus remained a mystery, but we felt confident that by April 10 we’d no longer be contagious and planned to head south to see him. I’d just sat down to start my workday on the ninth when he texted me: “Es. You may think about coming today.” In the anxious fog of his pain, he couldn’t understand why he hadn’t yet qualified for Maine’s law and needed me to figure it out. We packed up the car and left as soon as we could.

The following day, I took a leave of absence from work to devote myself full time to researching the law’s requirements. I connected with the head of Maine Death with Dignity, the advocacy group that had helped write and pass the legislation. The law had been in effect just six months, and just one person had used it. Dr. Edwards could lose his medical license if he failed to follow its requirements to the letter.

Up until this point, I’d pushed my dad not to give up entirely on medical intervention. I talked up the two Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs for ALS, which can prolong life by a few months. I emailed with Mass General’s chief of neurology about an impending clinical trial for new therapies. I arranged an emergency visit to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. My dad wasn’t interested in any of this. He went to Mayo only grudgingly, accompanied by my brother and a family friend, and refused further testing once there. His girlfriend had been providing heroic, around-the-clock care, but as his needs grew, I spoke with assisted-living facilities, nursing homes, and providers of 24-hour in-home care. He shunned those options, too. Every time I pushed, I risked alienating and upsetting him further.

Even as I tried to mask my frustration—how could he not do everything possible to have even one more day with us?—witnessing my dad waste away helped me understand his desire to escape. Being physically capable was essential to him. He was annoyingly militant about eating healthfully. He’d skied and rock-climbed with us into his 70s and had bigger biceps and firmer abs than anyone I knew close to his age. He’d also worked hard to build his retirement savings, part of the legacy he’d leave to his children and grandchildren. Particularly important to him was the Deer Isle house, which he’d spent the past decade turning into a home. The last thing my dad wanted to do was to deplete his bank accounts by paying people to care for him past the point he could enjoy living.

He hadn’t given up in the face of his decline. He kept doing what exercises he could, getting acupuncture, and meditating. Nor did he let his appearance go, insisting on a daily shave and putting on real pants instead of sweats, with help from the home health aide who came in a few hours a day. But he didn’t want to be remembered as a frail, dependent shut-in. ALS had snatched away the vitality that had given his days meaning. He no longer recognized his life. Perhaps that would make it easier to leave behind.

ALS patients make up the second-largest share of people opting for assisted deaths in the U.S., after those with cancer, data show. There’s no one test to identify ALS. Doctors conclude someone has it based on what’s called a “diagnosis of exclusion,” which is to say they systematically rule other things out. This characteristic of the disease, and my dad’s refusal to follow up with neurologists upon the first suggestion that it could be the cause of his body’s decline, had fed his denial that he had ALS. As I deciphered what remained to be done to get my dad qualified under Maine’s law, that denial emerged as the biggest hurdle. He didn’t have an official diagnosis, and his doctor couldn’t proceed without one. I scrambled to secure an emergency telemedicine appointment with a Mass General doctor my dad had seen back in 2018. As his iPad camera captured how difficult it had become for him to walk and raise his arms—evidence of the disease’s progression—she confirmed ALS without hesitation.

That worked. Mercifully, I wouldn’t have to take drastic measures to help my dad end his life. On April 17, I found myself behind the wheel of his black truck, driving the 20 minutes to a pharmacy in Portland, the only one in the state that sold the necessary drugs. I paid $365 and clutched the white paper bag like a precious heirloom. In it was the latest protocol, called D-DMA: one brown glass bottle containing powdered digoxin, which is normally used to treat irregular heartbeat but causes the heart to stop at extreme doses. And another with a mixture of diazepam, commonly known as Valium, which is usually used to treat anxiety but suppresses the respiratory system at high doses; morphine, an opioid pain reliever and sedative that also suppresses the respiratory system; and amitriptyline, an antidepressant that stops the heart at high doses.

The next day was my birthday, and Alex and I had persuaded my dad to let us take him for a walk outside in his wheelchair. “So we’ll go to Deer Isle tomorrow,” my dad proclaimed at one point out of the blue. No fanfare. It wasn’t a question. It was his way of saying it was time.

When morning came, my dad’s girlfriend got him packed and dressed and helped him into his truck. We stood back while they shared an emotional goodbye. The sky was clear as Dad, Alex, Fern, and I pulled out of the driveway.

A few hours later we crossed over my dad’s favorite bridge, suspended above the choppy waters of the Eggemoggin Reach, connecting the island to the mainland. His eyes welled up. We’d made good time and arrived well before dark. Alex carried my dad, piggyback-style, from the car into the house. My brother flew in a few hours later from California.

I slept beside my dad that night in his bed, waking to help him adjust his arms, drink water, and sit up to pee. I dripped blue drops of morphine into his mouth to ease the aches and help him sleep. It was intimate, odd, and beautiful, a role reversal neither of us had foreseen. I opened my eyes in the morning to find his trained upward, through the skylight. “Treat thoughts like clouds,” he said. “Just watch them pass by.”

That was Monday, which he’d said would be the day. We gathered around him, seated in the swivel chair I’d helped him pick out years prior to gaze out the windows at the Atlantic Ocean. We rummaged through the plastic storage bins where he’d tossed thousands of old photos over the years. We found a black-and-white print of his father from the 1940s that he hadn’t seen in ages, and it made him beam. We came across fading negatives of a naked woman, and we laughed.

The pharmacy had enclosed precise directions: The drugs had to be taken on an empty stomach. But as the hours wore on, he kept wanting to eat. Sourdough hard pretzels. A chocolate Rx bar. Tinned calamari and crackers with cheese. Soon enough it was dinnertime, and Alex made my dad’s favorite: pasta with clams, freshly dug by a neighbor from the flats in front of the house and dropped off that morning. We sat around the dinner table and drank good wine and talked about the women who’d come and gone in my dad’s life. He asked which one we liked best. The specter of death hung over us, but, after so many months plunged into the mental anguish of his illness, he could live in the now. He no longer feared his deteriorating body, or the prospect of a prolonged death. If only for a day, we had our dad back.

The night before, I’d read to him in bed from a book by his favorite poet and fellow Mainer, Edna St. Vincent Millay. I’d opened it to a random page: a poem called, of all things, The Suicide. Tonight it was Mary Mackey poems I looked up on the internet after we couldn’t find the book. I massaged his calves and quads and feet. He thanked me for helping him. I felt thankful, too—that he wanted me there by his side.

Would Tuesday be the day?

He kept us guessing until the end, which was maddening and exhausting and understandable. That morning, a health aide came to give him a sponge bath and a shave. She casually commented how much I looked like him—I was so clearly his daughter, she said—and I beamed with pride. We spent a while listing his favorite poems to share and songs to play at the memorial we’ll hold for him after the pandemic, and it made him smile. I read a letter my brother’s wife had written to him (the pandemic and two kids had kept her at home), and it made him cry. We meditated to the voice of Ram Dass. Fern toddled around in enviable ignorance, figuring out how to take her first steps.

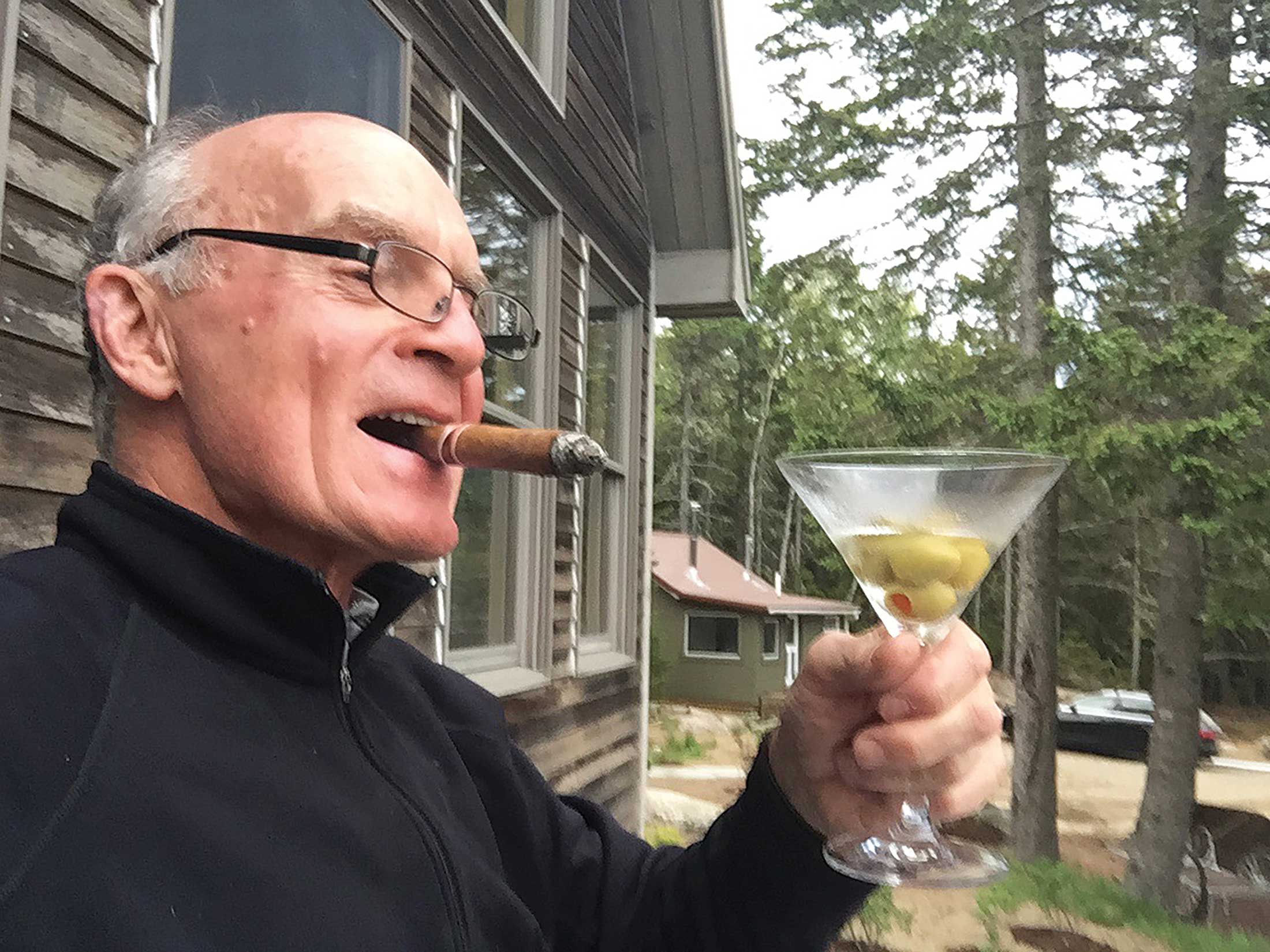

And then, at about 4 p.m., he declared himself ready to begin the process, with an anti-nausea drug. We wrapped ourselves in down coats and wheeled him outside to the front porch, where he used to sip dirty vodka martinis and smoke cigars after a hard day’s work. It would be weeks until the season’s last snowfall, but behind the house, along the forest path heading down to the water, the neon green shoots of fiddleheads were poking up through the earth and fresh spruce tips were emerging from the ends of the branches of the trees.

It started to drizzle, and we headed back inside. Dad asked us to move a framed black-and-white photo of his mother atop the wood stove he’d refurbished years ago. He said he hoped he’d see her. He said he’d miss not skiing with us again and “I’ll be all around you—just look for me,” or something to that effect. When the others stepped away, he turned to me and said he wouldn’t be doing this if he felt like his condition had left him any other choice. It felt like an apology. I told him I understood.

Réal and I stood at the kitchen sink and added water to the first powder—the digoxin that would slowly stop our dad’s heart—in a rocks glass with a redheaded canvasback duck painted on the side. There would be no turning back after this one. He stared at the liquid for a few moments, then gulped it down. “Only the good die young,” he said with a sly smile. Alex questioned what he meant. “Well, I haven’t been good,” he replied.

We followed it with shots from a fancy bottle of Irish whiskey he’d been saving, Redbreast 15 Year Old. He requested David Bromberg’s version of Mr. Bojangles and sang along. He said something about this being such an immensely better way to die than being hooked up to tubes in a hospital bed, and we all nodded. If ever there were a good way to go, Alex practically shouted through tears, this was it. Then we mixed, and Dad swallowed, the sedatives. “That was enough,” he said, leaving a few drops in the glass. “I’m dead.” And then, “Whoa, whoa,” and he closed his eyes for the final time.

For hours it looked like he was simply taking a nap. He snored. I sat on the floor holding his hand and rested my head on his upper arm. It wasn’t until around 8:30 p.m. that we felt his pulse finally give out. Strong heart. Strong guy. He would have liked that.

There were few instructions about what to do next—and no need, because it was an expected death, to call the police or an ambulance—so Réal, Alex, and I sat vigil for hours more until we felt ready to ask a funeral home to come to take the body. We plowed through an entire box of tissues. Simon & Garfunkel crooned. It kind of looked like Dad was still napping, mouth agape, but also not at all. His skin had grown pale, his body cool. My brother kept saying it wasn’t him anymore. He wasn’t in there.

Although he was born and spent most of his life in Maine, my dad didn’t discover Deer Isle until the 1990s, when he was consulting on a rural health project nearby. He loved it more than any other place in the world. I loved it, too, from my first visit shortly after he bought his house in 2010. It was a shell back then, and Alex and I slept on a mattress on the floor.

My dad always gave me grief about not spending more time there, but he also understood that I had a life and career in New York and then California. After his death, Alex, Fern, and I stayed for six more months. We were working remotely, and Fern’s day care was closed anyway, so we took advantage of the silver lining. As the pandemic worsened, causing lonely deaths in chaotic hospitals with goodbyes and last rites delivered over FaceTime, we came to appreciate even more my dad’s peaceful, graceful, at-home exit.

Sometime during the first week of July, I passed by a framed photo on the living room bookshelf, probably taken in the late ’80s or early ’90s. In it, my dad is dressed in a blue-and-white-striped rugby jersey. His face is young, his wrinkles less deep. I’d walked by it hundreds of times, but it struck me this time. It was almost like I didn’t recognize him, as if he were a stranger. I started to panic. Was I forgetting him already? Moving on too quickly? To see him only in photos and no longer in person was becoming distressingly normal.

It was late, and I climbed into bed and picked up a book he’d left on his nightstand by the Marxist critic and artist John Berger. I’d left off the night before on page 15. On it was a poem called History, the introduction to which my dad had marked with a pen: “The dead are the imagination of the living. And for the dead, unlike the living, the circumference of the sphere is neither frontier nor barrier.”

The pulse of the dead

as interminably

constant as the silence

which pockets the thrush.

The eyes of the dead

inscribed on our palms

as we walk on this earth

which pockets the thrush.

I’d never really understood poetry. Pockets the thrush? Thrushes as in songbirds? I searched the internet and failed to find anything that shed light on what the poem meant and why it might have touched my dad.

A few months later, I searched again and up popped an article about Berger on a British website called Culture Matters. It didn’t discuss that particular poem, but I emailed the site anyway.

“Yes well it’s a great little poem, no wonder your Dad liked it,” Mike Quille, the site’s editor, responded the next day. “And understanding it may help assuage your grief at his passing, as it is very much about life and death.” He continued on to explain how in this one, as with many of Berger’s poems, “death is seen and heard in the here-and-now, part of every life-cycle, whether animal or human. … Death and Life work together in Nature. … Earth is both the habitat and sustainer of the living, and the ‘pocketer’ and burial place of dead things. And that’s just what history is, a combination of life and death.”

I thanked him and told him a bit about my dad and the way he’d died. He wrote back once more. “Your Dad sounds like a man who appreciated life well enough to be able to handle death. Which is how you transcend its finality, I guess.”

Whether it was cleaning the kitchen or building a career, my dad had always told me: If you’re going to do something, do it right. And that independence was freedom, and free was the only way to live. His desire to die on his own terms made perfect sense given how he’d lived. He never hid from controversy. He embraced confrontation. You couldn’t talk the man out of anything: He was a my-way-or-the-highway type, confident in what he did and the way he did it, because it was the right way for him.

It turns out he was teaching me until the end. I couldn’t change my dad’s decision about how and when to die. Nor could I honor his right to be in control without surrendering my own. So I helped the man who’d brought me into this world to leave it.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!