By

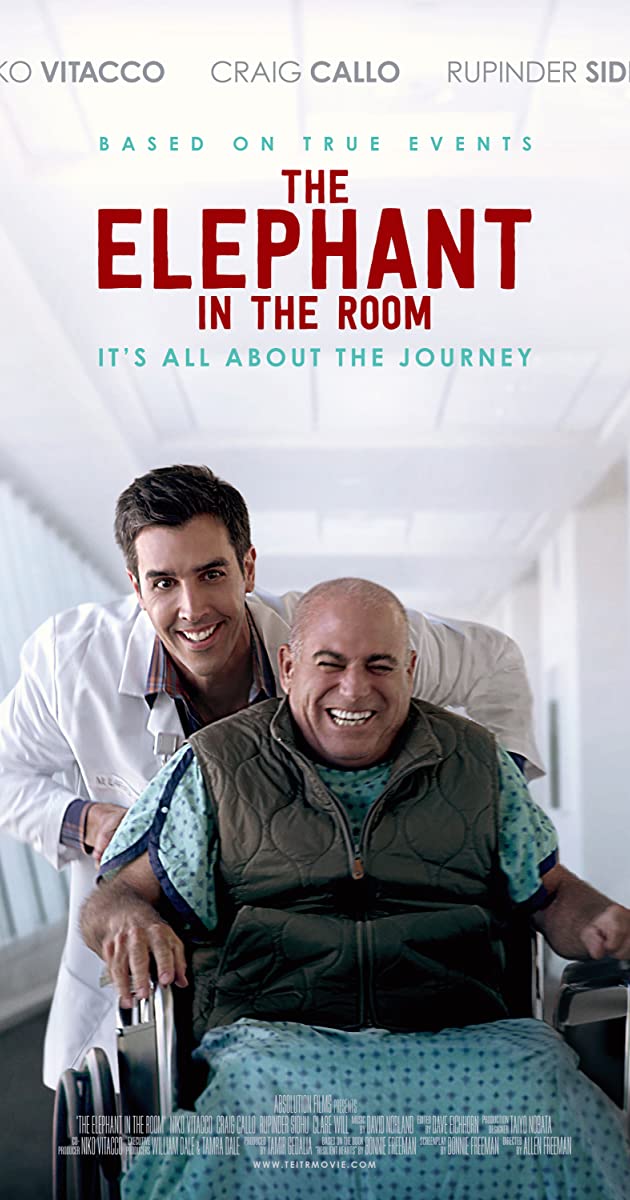

Public misperception is a barrier between patients and palliative care. Based on the true story of a nurse practitioner’s experiences with patients and families facing serious and terminal illnesses, the film “The Elephant in the Room” depicts the patient-centered interdisciplinary care that so many seriously ill patients need.

The film was written by Bonnie Freeman adapted from her novel, “Resilient Hearts: It’s All About the Journey,” based on true stories of her experience as a supportive care nurse practitioner for the Department of Supportive Care Medicine at City of Hope Medical Center located in Los Angeles. Shot throughout 2017 and directed by husband and photographer Allen Freeman, the book turned film brings an inside look into goal-concordant and patient-centered care through the eyes of those who provide it.

“Bonnie wanted to educate, that was her passion at the root of it all,” said Executive Producer William Dale, chair in Supportive Care Medicine at City of Hope. “She just wanted to make sure that our message got delivered. She had aspirations for us to break out of our little crowd that care about the cause, care about supportive care and palliative care.”

Dale also helped provide funding to support the film’s making.

According to producers, Freeman passed “unexpectedly and suddenly” before the film completed on April 26, 2018. She played an integral and hands-on role during filmmaking, working closely with Niko Vitacco, who played the lead role of nurse practitioner Michael Lafata.

Films like the “The Elephant in the Room” could help to raise awareness and improve understanding of palliative care. The medical comedy-drama, walks viewers through end-of-life care through a provider’s lens, including goals-of-care conversations. The comical drama is currently available on Amazon Prime.

As many as 71% of people in the United States have little to no understanding of what palliative care is, including many clinicians in a position to refer patients to palliative care or hospice, according to A Journal of Palliative Medicine study.

While no standardized definition exists for “palliative care,” the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) defines the term as “patient and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social and spiritual needs and to facilitate patient autonomy, access to information and choice.”

Roughly half of community-based palliative care providers in the United States are hospices, according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC). While a growing number of hospices are diversifying their service lines to include palliative care, many struggle to sustain and grow programming due to a widespread lack of awareness. These services remain relatively unknown and misunderstood among the general public, as well as within medical communities.

“Bonnie knew that storytelling was a way to help improve end-of-life care,” said Vitacco, actor and co-producer of Absolution Films. Vitacco read the following quote Freeman initially wrote to pitch the film. “‘I realized many health care providers did not know what we provided and the community was even less informed. I felt a film would reach a broader audience and could be a tool to promote discussions about effective ways to communicate the need for compassion and show the difference a dedicated palliative care team can make in the lives of each other, their patients and their families.’”

The film strikes a strong chord as the world comes face-to-face with a deadly pandemic. The COVID-19 outbreak has brought serious illness to the forefront, with the World Health Organization reporting more than 1.6 million lives lost globally since its onset.

“Something within this script resonated so strongly with me. I saw it as an opportunity to help people on a larger scale, to share a story that was meaningful and bigger than me,” said Vitacco. “Even more so now in a world where humanity can sometimes feel lost, this film can show the type of the side of people that we all want to become but sometimes struggle to be.”

Despite heightened focus, palliative services remain underutilized throughout the globe. The World Health Organization reported in August that only 14% of people who need palliative care currently receive it. Many countries ranked low in an international review of length of palliative care received by people with life-limiting and terminal conditions, including the United States and Australia.

Increasing awareness around the benefits of serious illness care was a stated goal for the filmmakers.

“Palliative care is still considered new within the medical world,” said Vitacco. “Our mission was to make it universally known and share it with not only the professionals, but the public as well to show them what is readily available to them.”

Initially released in Middle Eastern countries, “The Elephant in the Room” came out in Australia, Canada, Germany, India, the United Kingdom and the United States on Amazon on Aug. 21, 2020, representing a broader reach for the film’s universal message.

“The subject is universal and we just wanted to release it wherever we could,” said co-producer Tamir Gedalia of Absolution Films. “For me, the message was that we need to change the way we treat terminally ill patients. It’s universal in every country. There is no country that doesn’t have this kind of love and treatment, there is no relation to a village.”

The film’s use of the term “supportive care” to describe end-of-life care was deliberate. The term is becoming more common in the field as providers seek to avoid stigma associated with the words “palliative” and “hospice.” Numerous organizations rebranded in recent years to remove those words from their company names.

Scenes show providers both engaging with patients and behind closed doors in interdisciplinary team meetings. The film’s team includes the supportive care department chair, oncologist, neurologist, pediatrician, pharmacist, nurse practitioner, social worker, chaplain and a staff psychologist who collaborate from the point of the patient’s admission through his passing. The social worker role of Valerie Howard was played by Rupinder Sidhu, a licensed social work program specialist at City of Hope.

Filming took place onsite for 12 days at City of Hope to minimize disruption to patients and operations, according to Dale, who expressed reluctance at opening the medical center’s doors to filming but ultimately valued an authentic setting.

“My hope is that people elsewhere understand the field and get entertained, but then also imbibe this message that it’s about how you take care of each other and take care of yourself,” said Dale. “We’ve all had those moments as providers when we’re in too deep with patients and families and we’ve gone across that line. The team did an amazing job dramatizing that, and I think that’s what Bonnie wanted and it’s my deepest goal for the field and for the film. This is more than we could have expected and we couldn’t have hoped for a better product that’s actually getting seen.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!