Doctors will finally be reimbursed for talking about death with their terminally ill patients, but, Michael Nisco argues, very few of them know how to do that. Nisco, the hospice national medical director for Amedisys Home Health and Hospice Care, has taught at Stanford and Harvard medical schools. He founded the physician specialty training program in palliative care at the University of California San Francisco Medical School.

He writes that medical schools must do a better job of preparing physicians to help patients even when they can no longer heal them.

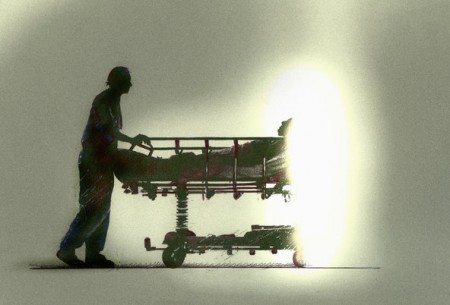

Dying Patients Deserve Physicians Educated in End-Of-Life Care

By Michael Nisco, MD

Starting this year, Medicare will, for the first time ever, reimburse physicians for having end-of-life discussions with terminally ill patients.

In the ideal scenarios, doctors ask patients to identify how and where they want to spend those final days, and then recommend the best options.

Question is, will physicians, as a result, be motivated to initiate more of these crucial conversations? Will patients? And will this long-overdue reform ultimately improve, both clinically and economically, how well the U.S. health care system delivers end-of-life care?

Nobody knows for sure. But this much is certain: Many physicians have received no training along these lines. Few are educated in how to carry on this kind of talk with patients in the first place, much less in shepherding patients compassionately toward death.

In 1999, only 26 percent of residency programs in the United States offered a course on care at the end of life as part of the curriculum, the Journal of the American Medical Association reported. Indeed, of 122 medical schools researchers surveyed more recently, only eight had mandatory coursework in end-of-life care.

Physicians all too often skip having an end-of-life discussion, or at least delay it as long as possible, even in the face of a major health crisis. Physicians are rarely prepared to conduct such momentous conversations with patients, least of all about anything as sensitive as advance care directives. We typically think and act short-term rather than looking ahead. But it’s more than that: Such conversations guarantee deep discomfort.

Acknowledging the approach of death means delivering a poor prognosis — and admitting to ourselves that we’re about to fail our patients forever. Doctors are hardly immune to living in denial. We can be unduly optimistic about how long even the sickest of the sick are going to stay alive.

After all, nobody wants to look death in the eye.

And in bypassing this opportunity and doing what we believe to be right, we’re actually committing a wrong, bringing serious consequences. Patients pay the price. Those who need to be alerted to and informed about end-of-life care may wind up ill-advised and even ignorant about the choices available and what they might mean.

And in bypassing this opportunity and doing what we believe to be right, we’re actually committing a wrong, bringing serious consequences. Patients pay the price. Those who need to be alerted to and informed about end-of-life care may wind up ill-advised and even ignorant about the choices available and what they might mean.

Terminal patients should have the opportunity to enter hospice care sooner than most do to take advantage of its clinical, emotional and spiritual benefits. They should also be granted the right to die at home if they so choose rather than in a hospital or a nursing home.

Pressure for these discussions to be imperative rather than optional is growing, and fast. The decision from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to compensate doctors for having these talks is only the latest breakthrough on this front.

In 2014, the Institute of Medicine came out with an influential report, “Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences near the End of Life,” that, among other calls to action, urged Medicare to approve such reimbursements for these counseling sessions. The American Medical Association soon urged the same. Massachusetts even became the first state to pass a law requiring doctors to discuss with terminally ill patients how they want to be cared for at the end of life.

Of course health care professionals in current practice should adopt the proper protocols, too. Accordingly, Amedisys Home Health and Hospice Care has undertaken its own national educational initiative. Over the last year, more than 3,000 of our employees, across our 80 hospice centers, have come together to watch the PBS documentary “Being Mortal,” based on the book by Atul Gawande, and discuss how to apply its lessons to caring for our patients every day.

We’ve secured Continuing Medical Education accreditation so we can credit every physician, nurse practitioner and physician assistant who completes an online course featuring the film. We’re also screening the film for physicians, nurses, social workers, home health workers and the general public at hundreds of locations across the country.

The broader solution here, at once simple and complex, is that more medical schools should develop curricula about performing end-of-life care in general and conducting discussions about it in particular.

We have to change how people die in this country – and, more specifically, teach the next generation of physicians how best to care for the dying. Here’s a prescription to get us started:

- Care at the end of life should be taught as an essential clinical skill throughout the continuum of medical education.

- Medical students should be exposed in all stages of training to dying patients and multidisciplinary teams who can instruct in a humane model of palliative care.

- Medical schools must train and hire more educators to demonstrate state-of-the-art palliative care for medical students, residents, fellows, medical school faculty, and physicians in practice.

- The following major goals should be the focus: establishing suitable communication skills; acquiring essential technical knowledge for treating symptoms and relieving pain; and learning to address the psychosocial, cultural and spiritual needs of patients.

Unless action is taken, we may see more physicians telling stories like this one, from Charles von Gunten’s “Why I Do What I do”:

The young man was ‘end stage’ and we could do nothing for him. He was short of breath and unable to talk and looked terrified. I had no idea what to do. So I patted him on the shoulder, said something inane, and left. He died hours later. The memory haunts me. I was ignorant and failed to care for him properly.

These improvements are already desperately overdue. Palliative care is the responsibility of all physicians, yet only an estimated 6,500 physicians are certified in hospice and palliative care. Only if we improve our overall approach will our patients and families ever truly have a chance to complete their life’s journey with honor and dignity.

Complete Article HERE!