— especially if you do it around another person

By Jenna Jonaitis

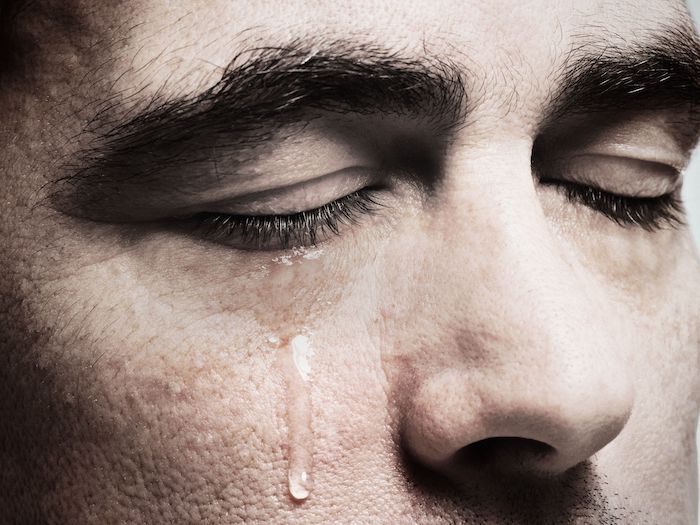

My husband and I were talking about experiences we have missed out on during the pandemic, such as having hospital visitors when our second son was born, when I surprised us both by bursting into tears. Once I started crying, I couldn’t stop. I sobbed and heaved for at least 20 minutes, as built-up stress and grief flooded out of me. Afterward, I felt a sense of peace, as if some of the weight of this pandemic had been eased — at least in the moments and days that followed.

Many of us have suffered over the past year, in ways both large and small. We’re more isolated than ever, while also taking on new responsibilities, such as remote schooling or working from home without child care. We may be grieving a death or mourning the postponement of a wedding. During these extraordinary times, stress and sadness can accumulate within us, especially if we suppress our negative feelings.

After my sobbing session, I wondered: Could crying be a way to help us cope and release some of that stress? And if so, is it a good idea to make ourselves cry?

The truth about emotional crying

There are three types of tears: basal tears, reflexive tears and psychic tears. Basal tears and reflexive tears keep your eyes healthy by lubricating them and ridding them of harmful irritants, respectively. The tears from crying are psychic tears, which Gauri Khurana, a child, adolescent and adult psychiatrist in New York, defines as “tears that are expelled during an emotional state.”

Certain theories about emotional tears have existed for centuries, such as the popular beliefs that crying removes toxins from the body and always leads to a feeling of catharsis, or emotional release, says Lauren Bylsma, an assistant professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Pittsburgh whose research has a focus on crying and emotional functioning. But research about crying is limited, she says, partly due to the difficulty of mimicking emotional situations in a lab and the ethical concerns of studying crying in more natural situations.

Thus far, the idea that crying provides a physical detox or flushes toxins out of the body isn’t backed by solid evidence, Bylsma says. And although catharsis can sometimes occur with crying, it doesn’t necessarily happen all the time.

“It seems that crying occurs just . . . after the peak of the emotional experience, and crying is associated with this return to homeostasis,” she says. “Crying might help aid that stress recovery process, but it may be that it’s only under certain circumstances, depending on the context in which the person cries.” There are other, more important factors that play a role in how people feel after crying, she adds, such as the social support they receive.

Another popular theory about emotional crying that has not been proved by research is that holding back your tears, or not crying despite experiencing grief, is unhealthy.

There is some preliminary evidence suggesting that when people “deliberately suppress their tears and hold it in, that there can be some negative effects of that, both psychologically and potentially physically,” Bylsma says. You might experience a headache by holding in stress, or you might feel less connected with others if you don’t share your needs.

Furthermore, “emotional restraint with suffering can then also translate into emotional restraint with joy and happiness,” says Jennifer Henry, director of the Counseling Center at Maryville University, because being able to cry is a way to acknowledge your feelings.

But Bylsma adds that it’s important to understand that there are significant differences in people’s tendencies to cry. You “might not have the urge to cry, and that’s not necessarily unhealthy,” she says. Nor is it necessarily harmful to suppress crying when it might have unwelcome consequences, such as “if you’re crying at work and it impacts your work performance or it’s an inappropriate situation.”

How and when crying is most beneficial

There’s a lot of variability in how you might experience benefits from crying, Bylsma says, but one key factor is social context: You’re more likely to experience benefits if you cry around supportive individuals.

“Crying and opening up really is a social cue to show vulnerability and to show that something’s not right in a way that can’t be expressed with words,” Khurana says. Crying tells others and ourselves that we might need help or that we might be overwhelmed — feelings that are all too common during this pandemic.

The amount of social connection and support fostered through crying varies by culture and who you cry around, Henry says. For example, crying in front of your best friend might evoke more comfort than crying around a co-worker. But the “social bonding, the eliciting support and connection” of crying is powerful, Henry says.

Whether you cry with someone else or by yourself, shedding tears can also help you “confront the things that are bothering you and face them and emotionally process them,” Bylsma says. “You might reach a new cognitive understanding . . . by spending that time focusing on it, because crying is something that’s very attention-getting for the individual and for others around you.”

>In this way, crying can act as a signal “to stop and take care of ourselves and to address that emotion” by dealing with underlying issues or stressors, says Roseann Capanna-Hodge, a Connecticut-based psychologist and integrative mental health expert.

Beyond receiving support from others and gaining a deeper understanding of what may be troubling you, crying is also a form of expression. “Emotional expression is healthy in general and something that we want to encourage to help people cope with the feelings they’re dealing with,” Bylsma says.

Should you make yourself cry?

Because crying can elicit some social and emotional benefits, is it healthy to make yourself cry? It’s not a one-size-fits-all solution, Bylsma says.

“It depends on how you’re making yourself cry and what your purpose is in doing it,” Henry adds. “If you feel like there’s unresolved sadness or something that you really, really need to get out,” she says, there could be some value in “trying to tap into the emotion that might create the crying.”

But Bylsma says you shouldn’t be concerned if you can’t cry, especially now. Some people may experience a “traumatic chronic stress reaction, where they might be feeling numbness” and have trouble being in touch with their emotions because of everything going on, she says.

Rather than forcing yourself to cry out of the blue, each of the experts recommends allowing yourself to cry — and even eliciting a crying session — if you feel stress or emotion building up. “If a person feels the urge to cry, and feels they need to get out their emotions, they should do it in whatever context will be most helpful, whether it be alone or with someone else or on a Zoom call,” Bylsma says.

“The first reaction people have most of the time when we feel the tears starting to come is we try to stop it,” Capanna-Hodge says. “Stop trying to put the brakes on it. Let it happen, and give it the time that it needs.”

Allowing for a good cry

To set up for a healthy cry, find a safe, comfortable place for yourself or with someone whom you trust; Bylsma recommends seeking out whomever you generally feel close to and share other kinds of emotional reactions with.

You can elicit crying by listening to a song that triggers emotion, watching a sad movie, talking with your therapist or simply telling a friend you need to cry. Pay attention to your thoughts, feelings and sensations. When you prompt a good cry, “your subconscious allows you to release things that may have held you back,” Capanna-Hodge says.

Crying can look different for everyone. Your cry might consist of a few tears or a half-hour of sobbing. Your crying will also depend on what you’re experiencing, whether it’s a job loss or a stressful week working on the front lines. But if you’re crying consistently over a few weeks or don’t know why you’re crying, it may be a sign to find a therapist who can help you determine what’s going on and provide support, Henry says.

You also can offer a comfortable, supportive space for your family and friends to cry. You don’t need to have a solution; it’s just important to be there with them. Doing so, Khurana says, often allows “the blossoming of love and just caring in a way that wasn’t there before.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!