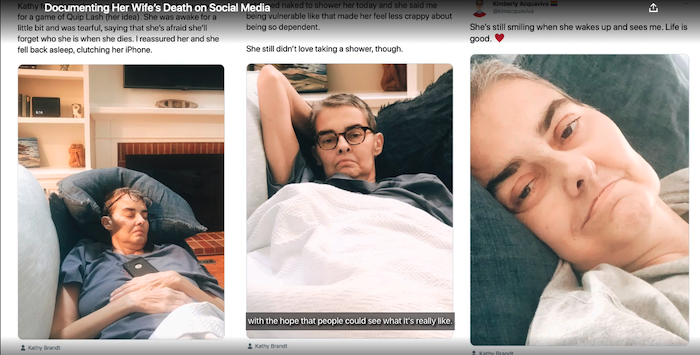

I chronicled what COVID-19 did to a hospital. America must not let down its guard.

By Kasey Grewe

You likely know that the number of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 is surging across the country. But headlines from distant states do not capture the horror of a hospital without enough intensive-care beds. I was an anesthesiology resident in a large academic medical center at the peak of the pandemic in New York City this spring.

During a time when journalists had little access to what was happening inside New York hospitals, I wrote regular email updates to friends and family. These messages—edited for length and clarity below—showcase the frightening reality of what care looks like in an overwhelmed hospital. (Where I describe individual cases in significant detail, I’ve obtained the consent of the patient or family in question.) The emails relate the experiences of health-care workers, and young doctors in particular: the anxiety, the fear, the overwhelming responsibility, and the ethical burden of hard decisions. Even after the pandemic is over, the weight of these experiences will remain with us for a lifetime.

These messages form a chronicle of what COVID-19 has already done in America and a reminder of what it could do again this winter.

Thursday, March 26

A senior anesthesiology resident holds the stat intubation pager, which goes off when a patient anywhere in the hospital needs a breathing tube right away. My co-residents and I first noticed that things were changing when the pager started to go off every few hours, and then every hour. When the hospital ran out of ICU beds, my department swiftly converted our operating rooms into a giant ICU. A co-resident and I spent Tuesday pushing beds and anesthesia machines around to plan how to fit up to four beds in an operating room. The “OR-ICU” fits multiple COVID-19 patients into one operating room, ventilated via the anesthesia machine’s ventilators. Their daytime doctor, an anesthesia resident in PPE, doesn’t leave their side until their nighttime doctor—another anesthesia resident in PPE—comes to take over.

On Tuesday night, one of my co-residents did 17 emergency intubations. Upon running to respond to yet another intubation page, she was horrified to see that the patient was one of our supervising physicians. Today, one of our surgeons was intubated. Off duty in my Upper West Side apartment, I hear an ambulance go by every 10 minutes. It’s hard to sleep. My colleagues wonder out loud: Is this chest pain from the virus, or just intense anxiety?

Wednesday, April 8

I spent the past few days and nights working in the OR-ICU. It is truly a scene from a science-fiction movie. When I put on my PPE (N95 mask, goggles, face shield, hair cover, gown, and two pairs of gloves) to enter the operating room, it almost feels as though the goggles are a virtual-reality headset. Upon entering the OR, I am confronted with the sight of four patients, all deeply sedated, each intubated and connected to an anesthesia-machine ventilator and many, many pumps for IV medications. Some—the lucky ones—are also connected to machines that perform dialysis. It’s loud. Huge fans filter viral particles from the air, and there are hundreds of overlapping beeps from the monitors, ventilators, and pumps. And it’s a mess. For days I wondered about some patient belongings in the corner: a pile topped with a pair of dark jeans and a cotton polo shirt. I inspected it more closely and saw the name tag of a patient who had passed away several days earlier. Yesterday I noticed a loose paper on the ground and picked it up. “Body Bag Instructions,” it read.

My team is responsible for the care of 12 ventilated patients. Of the 12, six are age 50 or under. Most are showing no signs of progress. One is a relatively young person who has been intubated for more than 10 days. We became optimistic that this patient, who had been breathing well with little support from the ventilator, could be disconnected from the machine. On Monday morning we removed the breathing tube, but the patient quickly deteriorated, and we had to re-intubate.

End-of-life care has always been the work of intensivists. It’s hard but profoundly rewarding to feel that you can help families through some of the most vulnerable moments in their lives. It’s part of the reason I chose to become a critical-care doctor. Pre-COVID, we were used to seeing patients pass away with at least one family member at their side. ICU doctors are desensitized to death, but even for us, the fact that people are dying alone is devastating to watch.

We have a team of doctors—who because of their age or other conditions are at high risk for the coronavirus—working from home as “family liaisons.” They call the family members of every ICU patient to give updates and help make decisions about care. When I arrived at work in the morning, our family liaison informed me that a family wanted to withdraw care from their father. He asked me to call into a Zoom meeting so they could see their dad and make a final decision.

Normally, we meet families in the ICU, but in this case I had never met the family. I called in wearing my full PPE, and was met with the faces of the patient’s children, who looked to be about my age. I introduced myself and asked what their understanding of the situation was. They explained that they understood their dad was very sick and that they didn’t want to keep treating him so aggressively. I expressed that I agreed with their assessment of his condition, and that we would support whatever decision they made. I explained that what they were about to see would likely be disturbing—that their dad might be unrecognizable to them—and asked again if they were sure they wanted to see. They insisted that they did. I slowly went to his bedside and flipped the camera so they could see his face. They immediately started to cry. I cannot imagine how jarring it must have been to see him for the first and last time with a breathing tube, deeply sedated, and in shades of yellow and purple. “That’s not Dad anymore,” one of the children said. I showed them the many machines and IV medications he was connected to. They agreed that he wouldn’t have wanted all this, and said they wanted to proceed with the withdrawal.

I asked if they wanted to say anything to him. I put my phone up to his ear, and one of them said, “I love you, Dad.” I asked if there was any music he liked that they wanted me to play. They said that he didn’t really like music. I offered to call a chaplain to pray with him and they said he would like that. I said, “I’m really sorry. This isn’t fair. I wish things were different.” They said, “Thank you, Doctor. Please let us know when it is done.”

I left the room and wiped my phone aggressively with bleach wipes. I called the chaplains’ office, only to learn that in-person visits were not being made to COVID-19 patients. The family accepted this. I asked a nurse to turn off the patient’s dialysis machine. I turned off the medications supporting his blood pressure, turned down his ventilator, and turned up all his sedative medications to make him more comfortable. I watched him die from outside the room on a vitals monitor while looking over data for other patients. I came back to do the official death exam and pronounce him dead. The nurse was overwhelmed, so I took out all his lines and bandaged him myself. I cleaned the grime off his face.

I called his son and told him that he’d passed away peacefully. His son confided that he was unsure whether they’d made the right decision. Their dad was very sick, and his chances of recovering to his baseline were definitely slim. But there is so much we don’t know about the disease. This man was in his 60s, a little younger than my father. If he were my dad, would I have withdrawn care? What would I have wanted to hear from a doctor on the other end of the line? “There is no right decision,” I said. “The best answer is just what you think he would have wanted. When we turned everything off, he passed away very quickly without the support. Maybe that was his way of telling us.” The son seemed to take solace in that.

During sign-out I told the overnight ICU supervising physician that I had withdrawn care on this patient. She marked on her map that we would have another open bed. “Oh, was he on dialysis?” she asked. “You freed up a machine. Maybe I can salvage this guy downstairs whose potassium is 8”—a level typically considered incompatible with life.

My lesson so far is that this disease, for the subset of patients who become critically ill to the point of requiring mechanical ventilation, is far worse than we ever imagined. It is certainly not pure respiratory failure. At the moment, we still have enough ventilators, but more and more I feel that this won’t save us. Our patients’ kidneys are failing, they remain febrile for weeks with no bacterial infection, they form blood clots in all their lines and likely their pulmonary vasculature, and, most strikingly, even the ones who look entirely ready to breathe on their own often fail when we remove mechanical support. The public conception that one ventilator means one life saved is evidently false.

Two of our own physicians remain intubated in the medical ICU.

Even when speaking to other doctors, my colleagues struggle to explain our situation. While we scramble to stay afloat, doctors from fancy hospitals in other states go on TV in makeup. Frankly, I’m not interested in what’s happening at Massachusetts General Hospital, or Stanford, or the Mayo Clinic. When people academically pontificate on possible treatments from afar, I feel frustrated by their lack of understanding of the issue. We have tried virtually every drug and none of them has worked. We are struggling to provide basic ICU supportive care. None of the experimental drugs will be of any utility in an environment where there are not enough hospital beds, doctors, and nurses.

Wednesday, April 22

I’ve been really shaken by the emergency intubations this week. The patients have been terrified. By the time I’m called, they are gasping for air. Because no visitors are allowed, they are alone. These encounters are emergencies and can be chaotic. We are all wearing PPE, so they can’t see our faces. I try to be kind and reassuring. I ask if they have any questions. But so often, as a result of the patient’s respiratory distress and the oxygen mask over their face, I can’t make out what they are trying to say. I have to say, “I’m sorry, I can’t really understand. We are going to put you to sleep now and put in a breathing tube.” I push medications to sedate and paralyze them, and then put a tube through their vocal cords. Looking down at them as they go to sleep, I’m the last person they see. And for the ones who don’t survive, I will have been the only one to hear—or rather, not hear—their last words.

The main resources we lack are respiratory therapists and ICU nurses. Our department has organized a huge operation in which doctors explicitly fill the roles of nurses and respiratory therapists outside of our regular physician shifts. This week, I’m working two overnight shifts as a respiratory therapist. The chair of my department is walking from room to room suctioning breathing tubes. Senior physicians are brushing patients’ teeth.

In the ICU, patients become voiceless and personless. We take care of their bodies for weeks: examining them, adjusting their ventilators, titrating their sedation, and carefully considering their medical management. But in the absence of family contact, we have no idea who they truly are. Last week, when we were rounding in the OR-ICU, I noticed my intern perusing a colorful website rather than the medical record. A note from a family-liaison doctor had pointed him to a support site for one of our patients. We saw for the first time that this patient was a teacher. The website had hundreds of comments from students and parents: “We are thinking of you every day!” and “We are praying that you make it through this!” There were dozens of photos of a middle-aged man with his students—in the classroom, at school sporting events, wearing different silly costumes. He had a huge, toothy grin. My intern stared at the website, stunned. It took my breath away. My attending physician said, “I can’t look at this. Please close it.” We get through our day in the OR-ICU by compartmentalizing—by ignoring the fact that our patients are people who are deeply suffering. When reality cuts through our fantasy, the job can be unbearable.

I’ve been asked when I think this will be over. There is a human impulse to believe that something this horrible will inevitably improve. But we cannot mistake fewer sirens for organic progress. If the curve has flattened, it is only through the deliberate work of millions of people who have accepted the reality of homeschooling their children, missing their friends and relatives, and forgoing their income. I think we have to trust the scientists who argue that reopening in the absence of a robust testing program or a vaccine will fail. Thank you for all of the sacrifices you have made, and continue to make, in the name of protecting those who are the most vulnerable.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!