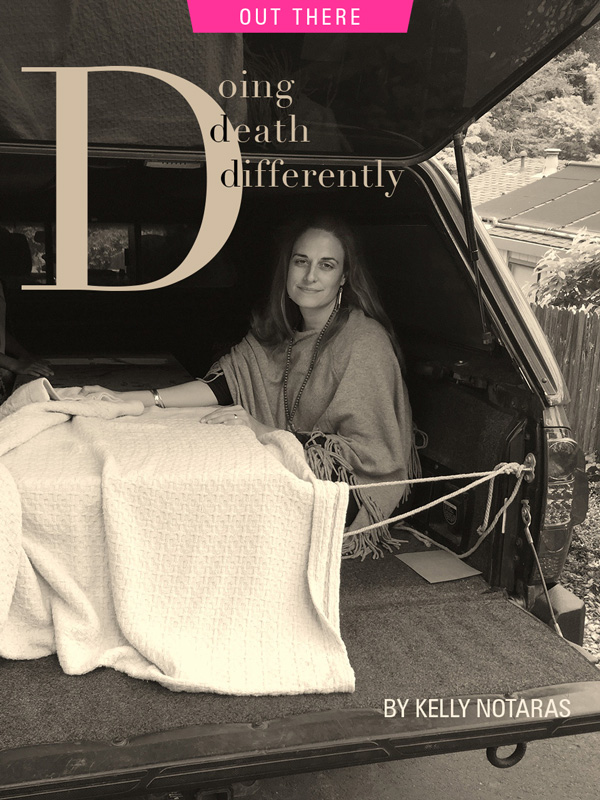

By MEG MCCONAHEY

When Carl Hamilton got the news that every parent dreads, his fatherly instinct kicked in. His son Chris was lying alone at the Sonoma County Coroner’s Office, the victim of a middle-of-the-night car crash. Against all modern convention, Hamilton decided he would not send his firstborn to a mortuary. Instead, he claimed the young man’s body and drove him home.

For three days and two nights Chris Hamilton lay in a simple hand-assembled wooden box in his parents’ Santa Rosa living room. Friends and family gathered beside him, experiencing their grief within the same modest tract house where Chris, a Giants and Green Bay Packers fan and Le Cordon Bleau-trained cook, had grown up.

They talked, shared stories, brought mementos and totems and shed tears. Carl Hamilton and other family members slept in the living room to be near their Chris, named for the storybook character Christopher Robin. In his 35 years, he had grown into a burly man of 6-foot 2 with a big smile, a wicked sense of humor and a compassionate heart.

The Hamiltons opted for an old-fashioned wake or home viewing, where a family spends intimate mourning time with their loved one. These kinds of funerals were once a common practice in American homes, often with women in the community assisting in “laying out the dead.” But with the increasing popularity of embalming and the professionalization of the funeral industry, family death rituals began to change.

At a time when most people “make arrangements” with a mortuary to deal with remains, the Hamiltons dialed back to the old ways in caring for Chris themselves. They oversaw every step, from making his box in the family garage and adorning it with art and messages, to transporting him to the crematorium where they sang songs and held their own service before bidding him good-bye and pushing his box into the flames. Virtually the entire family — three generations — participated.

“I wanted to slow things down. I hate funerals, the ones I’ve been to. I wanted my son home,” said Hamilton, a longtime director in community theater and currently a drama teacher at Cardinal Newman High School.

Soothe broken heart

It was, he reflected, like another production but one that, in its way, helped soothe his broken heart.

Just as women began reclaiming childbirth from strictly clinical hospital settings to home births, natural childbirth and birthing centers, an increasing number of people like the Hamiltons are reclaiming death rituals in ways that are more personal. It’s spawning a niche of services and products for home funerals and green burials, from shrouds to body oils to biodegradable boxes and urns. Increasing numbers of people are craving more control of the mourning experience, and see it a more normal way of dealing with the remains of a loved one, and a healthier way of experiencing their grief.

“I think we’re still just at the tip of the wave,” said Jerrigrace Lyons, who in the 1990s founded a group called now called Final Passages, to educate people about how to do their own home funeral and to provide support. The Sebastopol advocate is now a part of a larger organization, the National Home Funeral Alliance, which has grown to include members throughout the U.S., Canada, New Zealand and Great Britain.

“Death is a very emotional experience, a very powerful rite of passage and people want support at that time, and they should have it,” said Lyons, who sees her role as akin to the doulas who provide lay support during childbirth.

Most people who opt for a home funeral have had time to think about and take conscious steps as they or a loved one is dying. But for the Hamiltons, there was no time to weigh the pros and cons, come up with a plan or poll everyone in the family.

A missed plane

Fate in the form of a missed plane flight put Chris Hamilton on the road that led to his death.

The week he died he was supposed to be in Italy on vacation with his mother, Frances Hamilton, and his sister, Isla. But at the airport he walked away from the gate and didn’t make it back in time to get on the plane. That was Monday. He was hoping to catch another flight as early as Wednesday. But in the wee hours of the morning that day, Oct. 25, he was driving north on Highway 101 near the Highway 12 exit in his VW Golf when he slammed at 50 miles per hour into a tractor trailer that had been abandoned in the roadway. There were no skid marks, so investigators believe he must not have even seen it ahead. He died instantly; his small dog Davy survived.

“They found his phone in his back pocket so they didn’t find any distracted driving. No drugs or alcohol was suspected,” the father said.

Hamilton, 62, had actually driven past the accident on his way to work, not knowing it was his son. But he felt uneasy since Chris, who had been living with him and his wife Jamie Smith for the last couple of years, hadn’t come home that night or responded to a text. He even drove to his ex-wife’s home hoping Chris would be there. No one answered the door.

Jamie, who had helped raise Chris since he was four years old, was notified after daybreak by coroner’s officers who came to the door and left her with a list of mortuaries and directions to pick one. They said they would deal with everything else. Jamie was unable to reach her husband by phone in the chaos amid the Tubbs fire that was still smoldering. He had just been relocated to a temporary campus site after parts of the Newman campus burned. Deputies left a message with the school to notify Hamilton that he needed to go home for an unspecified emergency.

Jamie had “that awful conversation” with her husband as he pulled into the garage shouting “What’s wrong?!”

The couple wanted to see their son immediately, but were told he was not viewable. Hamilton spent hours contemplating what to do. He had read stories about people who had home funerals. By early afternoon he announced he wanted to bring Chris home.

Jamie said her sister tried hard to persuade her “that it would be a mistake we would regret, but Carl was steadfast.”

Jamie had her own reservations. Would people think they were weird?

Son Dylan Hamilton, 22, a filmmaker in Santa Fe, assured her that the Hamiltons, a theatrical family, are a little weird.

“This is who we are,” he said. “We do things a little differently. We’re a little off kilter and it’s important we keep doing things that way. This was the perfect thing.”

To his grandmother Pat Hamilton, 87, a home viewing was perfectly normal. She remembers when she was 16 and her grandma was laid out in the living room.

“We were close to her. We could see her. She wasn’t alive anymore but she was grandma.”

Jamie immediately got online and found Grace, a pioneer in the revival of home funerals, who helped them through the process.

Help with paperwork

Home funerals are legal in all 50 states. Grace navigated them through getting a death certificate, the application process and permit for the disposition of human remains that is required to transport a body.

The coroner took a week to release the body pending an autopsy. In that time the Hamilton’s put together their plan.

The decided they wanted an old-fashioned wooden box that they could decorate themselves, and then use to cremate Chris.

“A coffin connotes to me, this big, shiny massive thing with rails. It just seems so impersonal to me and not at all like who Chris was or what we are as a family, Jamie said. “We’re way more down-to-earth than that. I couldn’t imagine putting my kid in some weird steel container and giving him to somebody.”

She found a company online that sold simple Wisconsin pine boxes with rope handles, something meaningful to Chris who enjoyed visiting his grandparents in Wisconsin. Other natural caskets are available in materials like willow, seagrass and bamboo.

She paid almost $800 for the box and almost as much to have the 100-pound package rush shipped. It arrived in a kit on Monday. Family and friends were invited to come over and help with the assembly and decoration. Chris’s younger brother Darius Hamilton-Smith, 27, a lighting and set designer in Los Angeles, headed up the effort.

It was a sunny day and a buddleia in the yard was filled with butterflies, something that almost never happens. The family reached for humor in their sadness.

The Hamiltons shared a love for the quirky movie “Little Miss Sunshine,” in which a dysfunctional family steals the body of their dead grandfather from a hospital and drives off with him in their VW van so they won’t miss a beauty pageant. Jamie mod-podged a picture of the scene onto the coffin and wrote, “We didn’t leave you behind.”

Darius bought a “blank” from a local shop that makes custom baseball bats and turned it himself, giving the bat a trial run with a few hits before placing it with his baseball-loving brother in the box.

The elder Hamilton said he felt it was an important part of the ritual that he pick up his son himself, and he still feels the weight of his 250-pound body as it was lifted into the box. The coroner was adamant that the body was not in a condition for viewing. But Carl wanted to touch his son. Grace peeked in the bag and found a hand that was unharmed and that became something for people to touch during the wake.

Grace offered up her Toyota van to drive Chris home for the last time. He was laid out on the kitchen table, his blue body bag covered in a beautiful piece of fabric the Hamiltons had saved from a Shakespeare Festival.

“It felt really good,” said Jamie, “just holding his hand.” Grace showed them how to pack the unembalmed remains in dry ice. The room was adorned with photos and mementos, from t-shirts to Chris’s favorite Gummy candy to a logo plate from the old BMW his grandfather had given him and that he adored.

Many farewells

Some 50 friends and family members came by over a three-day period to draw or write on the box or leave a gift. Someone brought a hummingbird, a Native American symbol of peace, love and happiness. His sister, Isla Hamilton, wrote him a letter, sealed it and placed it in the box. Jamie’s sister sewed a pocket from lavish fabric and tucked a letter inside. Another sister made a “flower arrangement” out of wooden cooking utensils in salute to his work as a cook. Carl added a knife that a Navy SEAL friend had presented to him years before in recognition of his courage, and that he had given Chris when he left home to move to Colorado.

For those days, time was suspended and their home became a safe and intimate container for their grief.

”We agreed we would just let each other do what we needed to do and we ended up crying and bawling and hugging each other,” Jamie said. “Sometimes we just found ourselves standing and holding his hand for a half hour.”

The family stayed together throughout each step in the ritual. They took him together to the crematory at Santa Rosa Memorial Park and held their own little service.

“This wonderful friend of ours brought this beautiful glass mason jar. In it was dirt, leaves, rocks and all kinds of things. Then she wrote out this piece of what everything meant,” Jamie said. “It seemed so perfect. As we stood in front of the big shiny oven with his casket, Carl read it and I handed each piece to Frances, (Chris’s biological mother,) who put each piece in the box. It was beautiful.”

They sang songs — “The House at Pooh Corner” by Kenny Loggins and “Learning to Fly” by Tom Petty.

“We all said something,” Carl said. “We put the lid back on the box and we all pushed him in.”

Chose an urn

While they waited for his cremains they played catch outside with an antique glove that Carl had given his son one Christmas. Then they drove to Funeria, an art gallery in Graton that features unusual and handmade urns. They picked a piece by Seattle sculptor Tony Hopping, a primitive human-like form made from wood salvaged from the Russian River. It spins on a potter’s wheel.

“The moment I saw it, the joy and energy of Chris jumped at me. Each morning I will spin his ashes to get the day started with a smile,” Carl wrote on his Facebook page, where he continues to pour his feelings, his grief and his memories of his son, with art, photos and poetry.

At the crematory they stood vigil as a kind man with flames tattooed on his arms, carefully removed the ashes, sifted them and handed them back to the family. They held a joyous celebration of Chris’s life at the Bennett Valley Grange a week later.

As hard as it was, the Hamiltons nearly five months later remain united in their belief that mourning at home with Chris was the best choice for them.

“Going through all those steps ourselves was therapeutic, and very helpful in the grieving process,” Chris’s brother Darius said. “It wasn’t like Chris was out of sight and out of mind. And instead of just sitting around and doing nothing, there was always something to do.”

Carl said he took comfort in reclaiming the old ritual of spending time at home with a lost loved one, as well as inventing new rituals that felt right for his family.

“There were lessons learned by going through those rituals,” he said. “In taking time and talking with people and really listening, you get to the bare guts.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!