By Roxanne Nelson, BSN, RN

“So how is your sex life?”

That is a question that a great many cancer patients would love to hear from their oncologists, but unfortunately, sexuality is not a topic that gets much attention.

A panel of experts here at the Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium (PCOS) 2017 tackled the subject of sex and the cancer patient and presented preliminary data demonstrating how “low-tech” interventions can make a dramatic difference for patients.

Sexuality is a somewhat taboo topic in oncology care, and perhaps even moreso in palliative care, explained panel member Anne Katz, PhD, RN, certified sexuality counselor at Cancer Care Manitoba, Canada. “But we know that this is important to patients and their partners across the cancer journey.”

She cited a study (Psychooncology. 2011;21:594-601) that found that fewer than half (45%) of all cancer patients had a conversation with their healthcare provider about sex. By cancer type, 21% of lung cancer patients had such a conversation, as did 33% of breast cancer patients, 41% of colorectal cancer patients, and 80% of prostate cancer patients.

Men, it seems, get the “sex talk” a lot more frequently than women do.

According to Dr Katz, the “whole thing is skewed” by prostate cancer. More than twice as many men speak to their providers about sex as compared to women.

“If we didn’t talk about nausea, if we didn’t talk about constipation, we would be regarded as negligent, even indulging in malpractice,” Dr Katz pointed out. “Yet we are leaving out conversations about this very important quality-of-life issue, which persists into end-of-life care.

“Sexuality is much more than just intercourse. It is about touch and intimacy and about much more than what we do in the bedroom,” she said.

A recent study (J Cancer Surviv. 2017 Apr;11:175-188) again showed that a “preponderance” of men (60%) had a discussion about sex with their provider, whereas fewer than half as many women did (28%).

However, healthcare providers thought “they were doing a good job,” with almost 90% reporting that they were. “So there is a very large gap as to who is saying what and who is hearing what,” explained Dr Katz.

Another problem is that the cancer patient is much more likely to raise the topic with their provider, rather than the reverse. This is a problem, she pointed out, “because in every other area, we raise the topic with our patients, indicating that its important. By not opening the door, by not starting the conversation, we are saying to our patients that ‘this is not important and I don’t want to talk about it.’ ”

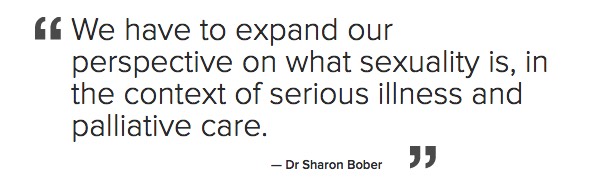

Panelist Sharon Bober, PhD, founder and director of the Sexual Health Program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, agreed with that summation. “We have to expand our perspective on what sexuality is, in the context of serious illness and palliative care. It’s too easy to be reductionist and think about whether some can or cannot have sex – this isn’t what it’s about.”

Sexuality, she noted, is a human experience across the lifespan. It’s a multidimensional experience that involves physiology, behavior, emotion, cognition, and identity.

“What we can take from some of the qualitative and survey work that’s been done to date is that expressions of sexuality can be a vital aspect of providing comfort and relieving suffering, maintaining connections in the face of life-limiting illness, and affirming a sense of self when other roles are lost,” Dr Bober explained. “When sexually is not made part of care, there is an implicit message that is it no longer important and/or the challenges cannot be addressed.”

Unfortunately, providers often took a medicalized approach, as was evidenced in one study (Contemp Nurse. 2007 Dec;27:49-60). Patient sexuality and intimacy were largely medicalized; the discussion remained at the level of patient fertility, contraception, and erectile or menopausal status, Dr Katz noted.

“There is a lot of active avoidance,” she said. She pointed out that the “patient reports the topic and the oncologist takes three steps back and flies out the door.”

Some of the reasons given for not discussing sexuality were reactions of colleagues, fear of litigation, and fear of misinterpretation.

The topic needs to be brought up in the context of quality of life, she emphasized, “but we need to open the door.”

There is the fear of not knowing what to say, but there is “Dr Google, there are books, there are experts, and if you don’t know, you will find the resources to refer patients to them,” Dr Katz said. “We have a responsibility to discuss sexual side effects of cancer treatment.”

Very Brief but Very Effective

Sexual function is profoundly disrupted by gynecologic cancer treatment, and 90% of patients with ovarian cancer report distressing changes in sexual function. “The good news is that ovarian cancer patients are living longer, and almost 50% of survivors will live many years post diagnosis,” explained Dr Bober. “But they often have to endure multiple surgeries and multiple rounds of chemotherapy, and sexuality and distress are generally not addressed.”

She pointed out that with ovarian cancer patients, “no one talks about this. The thought Is often that you have bigger fish to fry, you may not live anyway ― there are all kinds of reasons that this doesn’t get addressed.”

Dr Bober described an intervention that they devised at Dana Faber to address sexual dysfunction in ovarian cancer survivors. Not only was it brief, easily accessible, and “doable” by patients, but final results showed that it was quite effective.

The format was integrative. It was composed of a single half-day group intervention with a didactic teaching and experiential exercises, coupled with an individualized action plan. After the session was completed, the participants were asked to reflect on what was pertinent to them and what they were going to work on during the next 6 weeks.

The session was followed by a brief telephone call, in which the action plan was reviewed and additional support was offered if needed, to uncover additional challenges that needed to be addressed.

Because this was a pilot study, it did not include a control group per se, Dr Bober explained, but participants served as their own controls. This was accomplished by having a 2-month run-in period, during which women filled out surveys at baseline then waited for 2 months before completing the survey a second time before beginning the intervention. The purpose of the 2-month run-in period was to estimate changes in symptoms that could not be attributed to the intervention.

The design comprised three modules. Module 1 was targeted on sexual health education, which discussed vaginal health, enhancing arousal, and increasing low desire. Module 2 involved body awareness and relaxation training, in which participants learned pelvic floor education, progressive muscle relaxation, and body scan. Module 3 involved a mindfulness-based cognitive training, which sought to increase nonjudging awareness of automatic thoughts, with progression from avoidance/distraction to acceptance.

The cohort included 46 women with stage I-IV ovarian cancer who reported at least one distressing sexual symptom. The mean time since diagnosis was 6.3 years (range, 1 – 20 years). “Twenty years is a very long time to be dealing with distressing sexual problems,” emphasized Dr Bober.

Within this group, 13% were currently receiving chemotherapy, and 44% were currently taking medication for anxiety, depression, or pain.

In evaluating the program, 97% of the women found the it helpful, 100% found it easy to understand, and 95% found the it enjoyable.

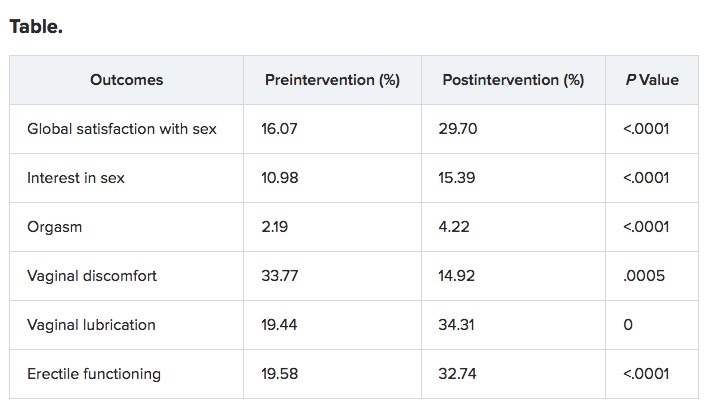

With regard to helping sexual functioning, “There were no changes during the run-in period, for the most part, demonstrating that time alone did not change the situation,” said Dr Bober. “But at month 2 after the interactions, there was significant improvement over multiple domains of sexual function. And for the most part it held over to 6 months.”

Although the pilot study was not focused on mental health per se, there was significantly less psychological distress observed in the participants, especially regarding symptoms of depression and distress.

It was a small pilot study, she emphasized, but the implications are that brief sexual health rehabilitation in the context of serious illness is effective. “There was meaningful improvement in sexual function and emotional distress, and improvements at 6 months.”

Dr Bober emphasized that there is an enormous need for evidence-based intervention research, with interventions conducted outside of an academic center in order to reach more people. “There is a need for identify optimal methods for delivery,” she said. “In some of the palliative care literature, patients talk about struggling with this issue within 2 to 3 months before they die, so this is not something that is relevant only if you’re well.”

Pilot Study in Transplant Patients

Similar to other oncology settings, sexual dysfunction is a common long-term complication for survivors of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCT), but it is rarely discussed, and interventions to enhance sexual function in this population are lacking.

The preliminary efficacy of a multimodal intervention designed to improve sexual function in allogeneic HCT survivors was very encouraging, reported Areej El-Jawahri, MD, instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivorship Program at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues conducted a pilot study to assess the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the intervention in a cohort of 50 patients. The participants were at least 3 months’ post transplant and had screened positive for distress caused by sexual dysfunction.

“There was a very wide age range, from 24 years to 75 years,” she said. “The median time from HCT at enrollment was 29 months, but there was also a wide range between 3 and 173 months.”

The primary endpoint of the study was feasibility: 75% of patients who screened positive would agree to participate and attend the first visit, and at least 80% would attend at least two intervention visits.

The majority of patients had acute leukemia (55%), and nearly 64% had chronic graft vs host disease (GVHD).

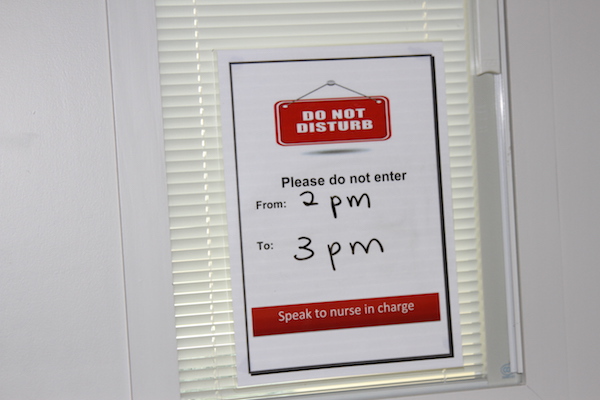

The format consisted of monthly intervention visits with trained study clinicians. The visits focused on assessing sexual dysfunction, educating and empowering patients to address this topic, and implementing therapeutic interventions that targeted their specific needs.

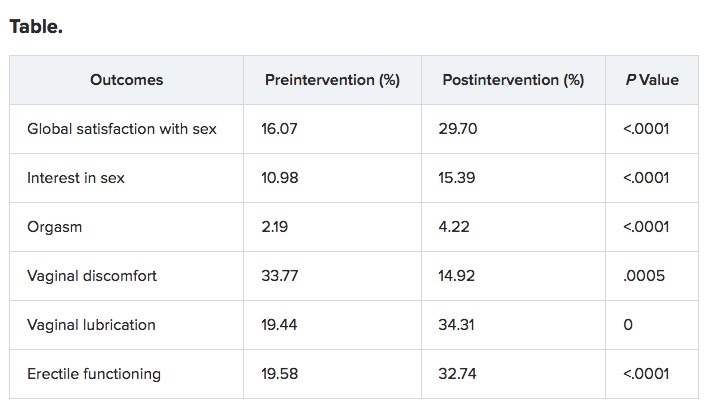

The PROMIS Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measure, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Bone Marrow Transplant (FACT-BMT), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) were used to assess sexual function, quality of life (QOL), and mood at baseline and 6 months post intervention.

The study met its primary endpoint of feasibility; 94% (47/50) agreed to participate, and 100% of this group attended at least two interventions. The median number of visits were two (range, two to five). The median duration of the first visit was 50 min; for the second visit, it was 30 min. In addition, 28% (13/47) had a partner attend an intervention visit.

Results were encouraging, Dr El-Jawahri pointed out. “Sexual activity in the group increased.”

Before the intervention, 32.6% of patients reported not engaging in any sexual activity; that number declined to 6.5% after the intervention.

In men, the following therapies were implemented: phosphodiesterase inhibitors (PDI) on demand (57%), psychoeducation (52%), penile constriction rings (48%), referral to a sexual health clinic (9%), daily PDI treatment (4%), topical GVHD treatment (4%), and hormone replacement therapy (4%).

For women, therapies included vaginal estrogen (67%), dilator (63%), lubricant (58%), psychoeducation (42%), topical GVHD treatment (42%), topical lidocaine (8%), and referral to a sexual health clinic (4%).

“All outcomes were clinically and statistically significant,” said Dr El-Jawahri.

The program was efficacious in improving QOL and mood.

“This has very promising efficacy, but we need to conduct a randomized clinical trial, and there is a need to asses longer-term outcomes,” Dr El-Jawahri concluded. “It also has potential for adaptation to other types of cancer survivors as clinicians to deliver this kind of intervention and allow for dissemination.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!