With cremation on the rise, cemetery space dwindling, and cryogenic freezing around the corner, the Vatican is facing some tough decisions.

By Leah Thomas

[T]he Catholic Church preaches the importance of following ritual, especially when it comes to burial practices. It stresses that, if possible, one’s whole body should be buried in a Catholic cemetery after carrying out a traditional Catholic funeral service, which involves the wake, the funeral mass, and the final interment prayer at the gravesite. If it was good enough for Jesus, reasons the Vatican, it’s certainly good enough for everybody else.

But in 2018, choosing cremation over full-body burial is so popular even Catholic priests are planning to skip out on classic casket burials. “I haven’t signed up for it yet, but yes, that’s what I will do,” said Father Allan Deck, a priest and professor of theology at Loyola Marymount in California.

“I think it’s a bit more practical,” he continued, laughing. “It’s easier to move the cremated remains around than it is a coffin, right?”

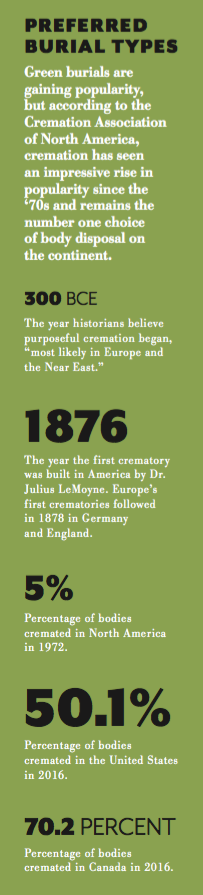

Cremation is prevalent now more than ever, with over half of Americans opting to be cremated rather than having a standard burial. And this percentage is projected to reach 78.8 by the year 2035, according to the National Funeral Directors Association.

Whether the Catholic Church felt pressured by the decreasing number of standard burials or by its own priests choosing the alternative, the Vatican released a statement in 2016 outlining the church’s new, more relaxed stance on cremation and the handling of cremated remains.

The new guidelines clarified that while cremation is acceptable, full-body burial is still preferred in order to (hopefully) emulate the Easter Day resurrection of Jesus Christ. “In memory of the death, burial and resurrection of the Lord, burial is above all the most fitting way to express faith and hope in the resurrection of the body,” the document stated.

“More and more of our funeral services are with cremains rather than with coffins,” Father Deck said. “It goes up every year, and the church has tried to respond to it in a constructive way, indicating certain things that should be observed if at all possible, like that cremated remains be put in one place, either in a cemetery or a mausoleum.”

The Vatican’s statement also made it clear that cremated remains, or “cremains,” should not be scattered, divided up, kept in one’s home, or preserved in mementos, pieces of jewelry, or other objects. But why is it so necessary for those ashes to be buried?

“The preservation of the ashes of the departed in a sacred place ensures that they will not be forgotten or excluded from prayers,” said Andrew P. Schafer, Executive Director of Catholic Cemeteries of the Archdiocese of Newark.

“We’ve had situations where homes have been sold and the next buyer finds an urn with human cremated remains in it simply because as the generations passed on, the family forgot about that person,” Schafer recalled. “And so it’s important to remain part of the Christian community and to be buried properly so you will always be remembered, especially in prayer.”

The fear of being “forgotten or excluded from prayers” derives from the church’s belief in the concept of purgatory, which is described as a post-death cleansing process where prayers from loved ones and other Catholics can pass a soul into heaven. If one’s body or ashes aren’t in one place — particularly a Catholic cemetery — they may not be remembered. The person may not receive prayers in their name. And they may never leave the eternal waiting room that is purgatory.

Catholics also stress the importance of burial in completing the church’s funeral traditions — traditions they maintain allow families to heal and grieve properly.

Catholics also stress the importance of burial in completing the church’s funeral traditions — traditions they maintain allow families to heal and grieve properly.

“There’s something psychological about bereavement and loss, and there’s a beauty that we offer with a funeral ritual,” said Peter Nobes, Director of the Catholic Cemeteries of the Archdiocese of Vancouver.

The funeral rituals Nobes is referring to being the three parts of the traditional Catholic funeral service.

“Rituals are important, particularly when there’s a loss in the family. Avoiding things, not wanting to do particular things or not spend money on a particular thing or cut corners here or there, can all be harmful to the family’s grieving process,” Nobes said.

But some attribute the rise in defying Catholic traditions to the high costs of Catholic traditions.

“You’re supposed to get buried in a catholic cemetery, which is also an income generator [for the church],” said Norma Bowe, a Kean University professor who teaches a course called “Death And Perspective.” She added, “I just have to wonder: are they continuing this tradition so that they’re still making money? Because it’s expensive to die.”

She’s not wrong. The average funeral, including embalming and burial, rings up to around $11,000.

The Catholic Church’s mandated burial practices not only present the issue of cost but have also led to a separate issue of cemeteries running out of room.

By the year 2030, the average baby boomer will reach age 85, increasing the death industry by 30 percent, according to the International Cemetery, Cremation & Funeral Assocation. Moreover, individuals over 80 years of age are less likely to choose cremation and more likely to opt for a full-body burial, according to the National Funeral Directors Association, further contributing to the space issue that Catholic cemeteries are attempting to alleviate without defying traditions.

Catholic cemeteries are beginning to feature “green burials,” or eco-friendly burial pods that recycle into the earth over time.

Other cemeteries are “doubling-up” — or placing the cremains of an individual inside an already used burial plot.

The rules for doubling, tripling, and quadrupling-up vary by region and diocese. In Nobes’ diocese, for example, up to three cremated remains are allowed to be buried inside one traditional full-body burial plot.

Some Catholic cemeteries are building up, rather than down.

“Many of our Catholic cemeteries have been building mausoleums for years now,” Schafer said. “So we’re kind of using the dead space above the cemetery — no pun intended.”

The Catholic mausoleums resemble that of the illustrious above-ground cemeteries in New Orleans, created as an adaptation to the city’s swampland rather than lack of burial space.

The rise in cremation is somewhat helping to alleviate the space issue, as cremated remains take up a significantly less amount of space than full body burial plots. Cremation “niches” can be as small as 12 inches square, according to Schafer.

Bowe, a Catholic, has faith that the church will eventually allow for more choice when it comes to what one has done with his/her ashes.

“I see the church changing,” she said. “I see them embracing folks they haven’t embraced before. Religion serves the people, so they have to think in terms of what the people want.”

When it comes to other modern death practices (or death avoidance practices) the Catholic Church is taking a stronger stance.

“People think they’re going to be frozen or do things to prevent death,” Father Deck said in regards to cryonics, or the practice of freezing bodies in order to potentially be revived in the future with scientific advancements. “But no one in human history has ever avoided death. Even Jesus died on Easter.”

Father Deck went on to clarify that while the church does believe in combating diseases and other health epidemics with medical research and advancements, it does not believe in preventing natural death.

“Death comes to us all. And as Christians we believe that the hour of death leads to the hour when we begin eternal life with the lord,” Father Deck said.

Regardless of Catholic burial recommendations, Bowe still plans to be cremated and have her ashes scattered.

“We have a cabin in New Hampshire that’s been our family retreat for years. I pick blueberries off an island that’s right in the middle of the lake,” Bowe said. “And that’s where I want to go. I want to be among the blueberry bushes. And I don’t think that makes me less of a Catholic.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!