More than 500 years ago, when the Spanish Conquistadors landed in what is now Mexico, they encountered natives practicing a ritual that seemed to mock death.

It was a ritual the indigenous people had been practicing at least 3,000 years. A ritual the Spaniards would try unsuccessfully to eradicate.

A ritual known today as Dia de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead.

The ritual is celebrated in Mexico and certain parts of the United States. Although the ritual has since been merged with Catholic theology, it still maintains the basic principles of the Aztec ritual, such as the use of skulls.

Today, people don wooden skull masks called calacas and dance in honor of their deceased relatives. The wooden skulls are also placed on altars that are dedicated to the dead. Sugar skulls, made with the names of the dead person on the forehead, are eaten by a relative or friend, according to Mary J. Adrade, who has written three books on the ritual.

The Aztecs and other Meso-American civilizations kept skulls as trophies and displayed them during the ritual. The skulls were used to symbolize death and rebirth.

The skulls were used to honor the dead, whom the Aztecs and other Meso-American civilizations believed came back to visit during the monthlong ritual.

Unlike the Spaniards, who viewed death as the end of life, the natives viewed it as the continuation of life. Instead of fearing death, they embraced it. To them, life was a dream and only in death did they become truly awake.

“The pre-Hispanic people honored duality as being dynamic,” said Christina Gonzalez, senior lecturer on Hispanic issues at Arizona State University. “They didn’t separate death from pain, wealth from poverty like they did in Western cultures.”

However, the Spaniards considered the ritual to be sacrilegious. They perceived the indigenous people to be barbaric and pagan.

In their attempts to convert them to Catholicism, the Spaniards tried to kill the ritual.

But like the old Aztec spirits, the ritual refused to die.

To make the ritual more Christian, the Spaniards moved it so it coincided with All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day (Nov. 1 and 2), which is when it is celebrated today.

Previously it fell on the ninth month of the Aztec Solar Calendar, approximately the beginning of August, and was celebrated for the entire month. Festivities were presided over by the goddess Mictecacihuatl. The goddess, known as “Lady of the Dead,” was believed to have died at birth, Andrade said.

Today, Day of the Dead is celebrated in Mexico and in certain parts of the United States and Central America.

“It’s celebrated different depending on where you go,” Gonzalez said.

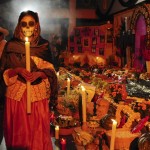

In rural Mexico, people visit the cemetery where their loved ones are buried. They decorate gravesites with marigold flowers and candles. They bring toys for dead children and bottles of tequila to adults. They sit on picnic blankets next to gravesites and eat the favorite food of their loved ones.

In Guadalupe, the ritual is celebrated much like it is in rural Mexico.

“Here the people spend the day in the cemetery,” said Esther Cota, the parish secretary at the Our Lady of Guadalupe Church. “The graves are decorated real pretty by the people.”

For more information visit HERE!