Australian oncologist Ranjana Srivastava says: In order to die a good death, it helps to have lived a good life. And a good life must involve contemplating one’s own mortality.

By Sally Pryor

It’s a circular philosophy that, as it happens, doesn’t feature nearly enough in the average person’s thinking, at least not in secular Australia. But for oncologist Ranjana Srivastava, living and dying are completely intertwined, and it’s those patients who are able to accept their own death – inevitable, albeit often untimely – who have inspired her to contemplate what it means to die well.

It’s a question, she says, that many doctors don’t manage to properly consider. The medical profession is focused largely on treating illness and making patients better.

“As I have matured as a doctor and became an oncologist, I have been very struck how there seems to be very little place – or no place, sometimes – in our day to talk about dying, let alone dying well, but simply dying,” she says.

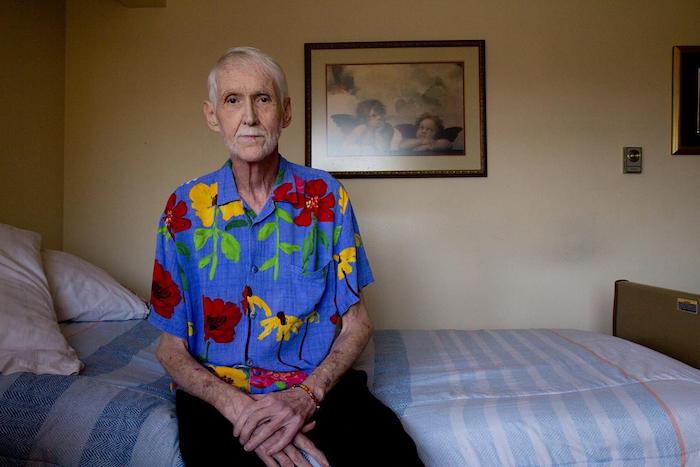

And yet her work involves dealing, daily, with dying patients, often caught up in the complexities of the medical system, at sea when it comes to dealing with what happens next. From the young woman, unable to work and far away from her family, to the 80-year-old man, refusing to accept an end point when it comes to treatment that isn’t working, Srivastava can see all the ways that our society – focused primarily in succeeding and moving forward – leaves little room for contemplation.

Srivastava has been writing, compulsively, since childhood, but it was relatively early in her medical career that she realised the power of story-telling, of human narrative, in allowing her to empathise with her patients, and to do her job properly.

“I’m incredibly aware that no matter how ambitious you are as a doctor, you can only do so much, so that’s why a lot of my public writing and thinking has been devoted around how do we empower everyone else, and how do you not just talk to doctors, but how do you go around doctors and talk to people and patients?” she says.

Her latest book, A Better Death, is a meditation on all the different ways in which death, and our awareness, can give meaning to our lives, even without a terminal illness.

“I guess I saw from an early age that what resonated with me, even as a trainee doctor or even going back as medical student, was someone’s story, because you could present a sterile case,” she says.

We’re sitting in a bustling Melbourne cafe, amid a noisy Saturday morning brunch crowd. On the face of it, it’s a jarring setting in which to nut out the concept of death, but Srivastava has a tranquility about her – a calm and blessed kind of reason – that makes you think she’d be the perfect person to have to deliver bad news, and to guide someone through the process of dealing with a terminal diagnosis. Those familiar with her writing – she is a regular columnist in The Guardian – will know that her commentary often starts with the story of an individual. It’s these personal stories that often drive the point home more vividly than any textbook.

“When I began writing, I thought, well how do I convey what I feel without illustrating why?” she says.

“And I continue to think that the way we empower people and the way we educate people is through letting them get a glimpse of themselves in each of those patients.”

One of the most important lessons she has learned is that everyone has the ability to control the way they die, through the way they choose to live out their last days. The many stories in A Better Death bear this out in different ways, but all with the same ultimate conclusion: if we could all live knowing that we will one day die, our lives will have more meaning, and we will be more motivated to leave some kind of legacy. Insisting on further treatment, even when it has become futile, or refusing to make arrangements for family and help them plan for the future, can make dying well impossible. But how individuals respond to dying has as much to do with society’s fear of morbidity, of talking about death, as with the individual.

“I absolutely think we have control over it, but the more I work, I think that it needs to be almost a societally determined thing,” she says.

“I think it’s very difficult for an individual to do this on their own, because there are so many forces. I will see this, where one of my patients will say, ‘I think I’m ready to just go peacefully, to stop treatment, to focus on being outside on a day like this and enjoying the gardens’, and someone else, who has not come to terms with their mortality but someone close to that patient, will have a different view. And I think it’s always easy to get taken in by that, and I think our medical system makes it very difficult to call it a day.”

Ultimately, she says, dying without a sense of peace is costly, both to the individual, and to society at large.

“There is an enormous cost to the family and to survivors, and this borne out by research and evidence, and then there is the cost to the taxpayer and society, so at every level there are serious costs,” she says.

“I think it’s driven both by patients and doctors, I would say, I don’t think every doctor is pushing patients to have more treatment, to not adopt palliative care, to not think about quality of life, I don’t think it’s as binary as that, and I think it goes back to the kind of society we are. There’s a lot of instant gratification in life – you want something, you get it. You see something, you can buy it, and health literacy is low in general. So I think people genuinely have trouble believing that many chronic illnesses and terminal illnesses cannot be reversed, and are not curable.

“We all have to ask this question of ourselves as to how we are going to contemplate our mortality and not just leave it to our doctors.”

And yet, she says, her work – and the world in general – is filled with examples of hope. While she is “continually astonished” by the number of elderly patients who, when asked, say they have never thought about dying, she is often consoled by examples of people who have thought the whole thing through.

“Just in the news I was listening to Bob Hawke’s widow speak about his death, and one of the things she said that quite struck me was Bob felt he had nothing else that he wanted to do – he was ready,” she says.

“And I thought, here is a man who has soared to the heights of accomplishment, and somehow he has managed to step back and back every year and every decade, until he has reached a point where he says, I have done what I need to do… I found that remarkable, and that’s why there is so much peace associated with him – he lived to a good age, he was able to live well, but he was able to articulate to the family left behind that he was ready to go, and I think it’s very consoling.”

How does she think she will come to deal with her own mortality?

“That’s a really good question. I would like to think that a career in oncology will not have been wasted when it comes to my contemplating my own mortality,” she says. “The reason I could never be sure about this is that I see how people can change when they are ill. It’s very difficult to be over-confident about how you would be when you are sick, when you are speaking about it when you are well. It’s something that each of us has to experience for ourselves. But I do feel that I am more blessed than most in having a lot of good teachers.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!