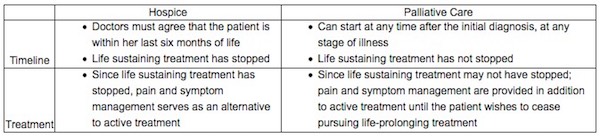

I am dying of ovarian cancer. I do not know how long I have to live. I have endured radical surgery, 65 chemotherapy treatments, countless trips to the emergency room and admissions to the hospital to extend my life. Now, my illness has developed resistance to treatments, and the last two drugs did not slow the growth of my tumors. I can die from a combination of chemotherapy and cancer or from just the cancer itself. I recently decided to cease treatment and pursue palliative care so I can minimize my suffering and maximize the quality of life that I have left with my wife, Stella, and our beloved dog, Adina.

I love my life, but now I need to plan for my death. I would like the option of medical aid in dying, which is authorized under D.C.’s Death with Dignity Act and that took effect in February 2017 for those terminally ill patients who meet strict requirements. The law allows mentally capable terminally ill adults with six months or less to live to get prescription medication they can decide to take if the suffering becomes unbearable, so they can die peacefully in their sleep, at home, surrounded by loved ones.

March 23 was a wonderful day for me and other terminally ill D.C. residents. President Trump signed an omnibus spending bill that did not include a House-passed provision to repeal the law or an administration proposal to thwart funding of its implementation.

Coincidentally, March 23 also was the 20th anniversary of the first prescription for medical aid in dying in the nation, under the Oregon Death With Dignity Act, the model for medical aid-in-dying laws in the District and five other states.

Before the federal spending bill was enacted, I lived in a state of uncertainty. I feared that opponents would be successful at invalidating the law. Fortunately, they were not. The law has been upheld, and the D.C. Department of Health issued rules last June to implement it, but health-care providers have not done the work necessary to allow patients such as me to use it. The threat that the law might be repealed made it unrealistic for doctors, health-care systems and pharmacists to invest the time to develop policies to participate in it. The D.C. Department of Health confirmed at its performance oversight hearing in February before the D.C. Council, at which I testified, that not one resident has obtained a prescription since the law that took effect more than a year ago.

Now, almost two months after the hearing, I still cannot find a physician who is willing to write a prescription for medical aid in dying. I and other terminally ill residents in the District need a compassionate doctor to come forward and embrace this option for dying.

I have been surprised at how many people, including physicians, do not know that medical aid in dying is now legally authorized in the District. Assumptions that congressional opponents would defeat the law brought its full implementation to a standstill.

Now that the immediate threat of the law’s repeal is over, I would like to encourage the D.C. Department of Health to work with health-care advocacy organizations such as Compassion & Choices, which helped implement the Oregon law, to launch an education campaign here and put the law into action. This collective effort would require working with D.C. doctors, health-care systems and pharmacists not only to explain the rules but also to consider any changes to ensure that the law does not discourage participation. Terminally ill patients need to know that medical aid in dying is an option.

It also took five months after the Oregon law went into effect for the first doctor to write a prescription. Once he did, others followed. Oregon now has an end-of-life care system that recognizes this compassionate option for dying.

More than a dozen safeguards in the D.C. law have been time-tested for a combined nearly 40 years in states that have authorized medical aid in dying without a single documented case of abuse or coercion. The D.C. rules are more complicated than those in other states, which might make it harder for terminally ill D.C. residents such as me to access this option to die peacefully in their sleep, at home, surrounded by loved ones. The result would be needless suffering.

It’s time we make compassion the priority of this law.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!