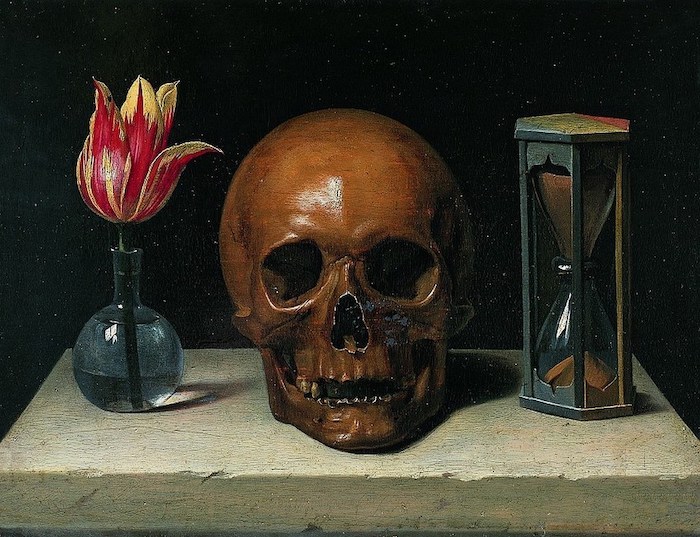

Why how you die matters

By Dominic Rech

It’s approaching 1 a.m. in Bilborough, a suburb of the British city of Nottingham. Peter Naylor, 70, is slumped in his bed, only yards from the front door of his small bungalow.

He can’t walk, so we unlatch the door and reach him immediately. The low buzz of an oxygen concentrator greets us.

Tubes run around Naylor’s ears and across his face and curl up into his nostrils. Framed family photos are nestled on a shelf by his side, each capturing intimate moments from his life.

We too are experiencing an intimate moment with him — but for an entirely different reason.

He’s dying.

A Nottinghamshire hospice team that cares for the terminally ill is three hours into a night shift. Naylor is the third patient they are visiting.

He’s been struggling with diabetes and has had multiple heart attacks. His breathing is heavy and pronounced. He exhales before opening his mouth slowly to say, “I’m stuck on this bed. I have been for more than one year. I can’t get off. I can’t go to the toilet. I can’t do anything. I just lie here.

“I’m near the end of my life. It could be any day now.”

Outside access to hospice night services, like this one, is unusual given that patients are at a very vulnerable stage of life.

But the hospice team granted CNN access because they want to show how palliative care is provided in the UK and make us think more about the kind of death we want for ourselves and our loved ones. The topic is close to my heart because the team looked after my father before he died this year.

“We all think we are immortal, so we want to put more money into saving lives; no money is being put into palliative care because we don’t accept we are going to die,” said Tracey Bleakley, the chief executive of Hospice UK, the umbrella organization for hospices.

‘It means everything’

Hospices offer specialist care and support to people with terminal and life-limiting illnesses. They coordinate with the UK’s National Health Service to provide care for people who are often in the end stages of life, commonly those who no longer want to be in the hospital and want to receive care at home.

It costs £1.4 billion ($1.8 billion) a year to run hospices, according to the charity Hospice UK. They are funded partially by the National Health Service but rely heavily on fundraising and donations.

During our time with the overnight hospice team, we met multiple people receiving end-of-life care. Given the sensitivity of their personal circumstances, some patients didn’t want to be interviewed or photographed.

Naylor was willing to speak to us. After leaving a care home, the 70-year-old opted to receive end-of-life treatment in the comfort of his own bungalow.

But his condition progressively worsened. On one occasion, he fell while trying to go to the toilet. He was alone and unable to move. It was three hours before anyone came to help him.

As a result, the care he receives has been ramped up, and he not only gets visits from the overnight hospice team but now has a full-time carer who lives with him during the day. The extra support allows him to relax and sleep better.

“It means everything,” he said. “It’s the nighttime when I get frightened, when I am here on my own. But I roughly know when they are coming and can call them if I really need them.”

The modern hospice movement took off in the UK in the 1960s, says Allan Kellehear, a professor specializing in end-of-life care at the University of Bradford. It spread to the United States in the 1970s.

Life expectancy was increasing, and the way people were dying was fundamentally changing, he said. More people were dying of long-term, chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular diseases and cancer rather than infectious diseases.

Hospices took up the mantle of caring for people with these long-term terminal illnesses. Now, there are more than 200 hospices in the UK. The number of hospice programs in the United States has been on the rise since the first program started there in 1974; there were 5,800 as of 2013.

However, in many low-income and middle-income countries, end-of-life care is poor, according to The Lancet Global Health journal. Tens of millions of people in need of palliative care have severely limited access, even to oral morphine for pain relief.

Naylor is adamant that he wants to die in his own home — something that happens to less than a quarter of people in England, according to the UK’s Office for National Statistics.

He’s not alone. Before meeting him on the overnight hospice shift, we visit the home of Harry and Serena Perkins in Nuthall, Nottingham, just before midnight.

It becomes obvious that this visit is a routine one for both the hospice team and the patient.

We are welcomed by Harry’s warm gaze in the hallway. The 96-year-old was an engineer during World War II. After quickly greeting us, he shuffles off into the lounge with his wife.

He has been married to Serena since 1973. They met when Harry was checked into a hospital with pneumonia; Serena was his receiving nurse.

“I would have said this is the finest girl I could have ever married,” he says, perched on the sofa next to her.

Harry, who has bowel cancer and heart problems, uses the day support provided by the hospice once a week, when he sees friends and accesses day therapy. He is also visited by the night support team about 11:30 p.m. every night.

“I thought it was a nuclear bomb that was going to take me, but that’s finished. So it will be my heart or the cancer that takes me.”

Despite his health, Harry seems more concerned about Serena’s well-being than he is about his own.

“We look forward to them coming every night. They are lovely people. They take me upstairs to bed, get me changed,” he says. “But they also talk to my wife. Keep her company, which is very important.”

Serena too is grateful. “I didn’t realize what a weight I had only my shoulders until they came. It’s really given me my freedom back in a way,” she says.

The care helps enable Harry to continue living with Serena in their home. It allows him to enjoy the quality of life he wants.

As we get ready to leave, Harry stands to get ready for bed. He shakes my hand firmly and mumbles a proverb from former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill: “Never give up. Never, never, never.”

Who’s providing the care?

The Nottingham hospice CNN spent time with is a charity.

Although a third of its income comes from the UK’s National Health Service, the rest comes from fundraising; the hospice has to raise an average of £7,000 (about $9,000) a day in order to operate the services it provides, according to Jo Polkey, head of care at Nottinghamshire Hospice. Many hospices across the country face a similar funding shortfall.

“Somebody that requires palliative nursing care is when there is no treatment options left. Trying to make someone as comfortable as possible. We want to add to their lives rather than think of it as the ending,” she says.

Its main service is Hospice at Home, through which more than 60 nurses and health care care assistants provide care at home to people with terminal and life-limiting illnesses. They also provide the overnight support teams, a day therapy unit, and a bereavement care and support service.

“We are often dealing with people very much at the end of life and in the last few days, weeks and hours of life,” Polkey said. “I think our average length of stay [of a patient] is about 26 days. They don’t stay in the services very long before they die.”

What does it take to be a member of a hospice team? One of the first things she says is that they are very “resilient.”

The night shift is arguably where this is most palpable.

‘People die on your shift’

Two overnight carers, Deborah Royston and Sonia Lees, describe the highs and lows of their jobs in between visits to patients.

Aside from the late hours, the job requires a lot of driving, with many of the patients living across Nottinghamshire, a county near central England that is home to just over 800,000 people. The shift usually usually starts at 10 p.m. and finishes before 7 a.m.

Royston says she finds it particularly difficult when she develops close relationships with patients.

“It’s really sad … to deal with death on a daily basis. Sometimes, people die on your shift, but it’s good you can be there for both them and the family members in that time of grief.”

Another visit we made was to the Wollaton home of Linda Wagner, whose husband, Bob, relies on overnight hospice support. He has progressive supranuclear palsy, a rare condition that can cause problems with balance, movement, vision, speech and swallowing.

“I know some people don’t believe in angels. Well, I do, but that is how I would class [overnight carers] — as angels,” she said. “I didn’t know the support was out there before. If I’m struggling, I know there are other people out there going through the same thing. It’s just a wonderful thing.”

Despite difficulties that come with Royston’s field, she described the job as her “passion.” She’s been helping provide night support for 12 years and finds the opportunity to build relationships with patients and their families fulfilling, even though it can be heart-wrenching.

“I just love it. It makes my heart feel good. I get quite emotional about it because you meet some nice, wonderful people.”

A looming crisis in palliative care?

A pun doesn’t always seem fitting when talking about death, but Polkey’s use of one seems to strike a chord: “People are dying to come to our services,” she says.

Over the past three years, hospices have helped more than 200,000 people across the country annually, Hospice UK’s Bleakley says. However, research by her organization in 2017 found that 118,000 people each year could benefit from hospice and palliative care don’t receive it because they live in an economically deprived area, live alone or have a certain type of terminal condition, among other reasons.

Bleakley thinks there is a crisis in palliative care that is only going to get worse.

“We had a massive baby boom after the war, and now those people are starting to die, so we are already going to have an increase in the death rate. We are all living longer, and we are all ill for longer at the end of life.”

The UK’s aging population is only going to increase the pressure, Bleakley says. In 2017, 12 million UK residents were 65 and older: approximately 18.2% of the population, according to the Office for National Statistics.

In a survey at the start of this year, more than 8 in 10 UK adults said the role of hospices would become more important in the next decade.

Bleakley was also worried about what the UK’s planned exit from the European Union might bring.

“Anything that affects consumer confidence, from companies having extra money for supporting hospices financially to people choosing to run a marathon to raise money — numerous things are affected by Brexit,” she said.

“And on the work force side, we will see more members sucked out” of the National Health Service.

Inclusivity challenges

Another challenge for practitioners is inclusivity.

Kellehear, of the University of Bradford, says that not many ethnic minority groups in the UK are accessing palliative care.

Nottinghamshire Hospice’s Polkey noted, “we look after a lot of white middle-class people. However, we are sat in one of the most diverse cities in the country. … We desperately want to reach into communities. Diversity is something we are working on.”

Hospice UK is running a campaign called Open Up Hospice Care to try to address this issue.

“There are people in the LGBT community … minority groups, people in prison — a lot of these people feel that a lot of the traditional services don’t work for them,” Hospice UK’s Bleakley said.

She also says that funding is going to be a fundamental issue for hospices.

The National Health Service’s Long Term Plan, earmarking the UK’s key health plans and priorities for the next 10 years, includes a bigger focus on community care and training people in palliative care, but Bleakley says there is no indication that any more funding would be put into palliative care.

“It costs 1.4 billion (pounds) a year to run hospices, and the NHS is putting 350 million in; they are not putting in the true cost of care or anything like it.” she said.

However, she doesn’t just hold the government responsible. She says society as a whole has to be more engaged when it comes to end-of-life care.

Kellehear agrees. He promotes the idea of compassionate communities and cities, a more holistic approach to palliative care that includes the bereaved as well as those who die.

It is based on the idea that care shouldn’t fall simply to doctors, nurses and the surrounding families of dying people. Instead, the wider community should step in to support people with terminal illnesses.

“We shouldn’t wait for disaster to happen. It’s about going into the schools, going into the workplaces, and saying ‘look, this is everybody’s business. What are you doing to do your bit?’ There’s not enough of that going on in the UK.”

For example, he says, schools should prepare kids for what to do should a fellow student lose a loved one.

“The people we keep forgetting in palliative care is the bereaved, who often suffer from similar social consequences as people with life-limiting illnesses: depression, anxiety, loneliness, social rejection and even suicide,” he added.

“These people are best helped when communities come together to support the people who are at risk of these things.”

Bleakley thinks we need to face up to the reality of death more often.

“A good death is a legacy for the people we leave behind.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What other advantages does palliative care offer?

What other advantages does palliative care offer?