By Bob Tedeschi

[A] new generation of immune-boosting therapies has been hailed as nothing short of revolutionary, shrinking tumors and extending lives. When late-stage cancer patients run out of other options, some doctors are increasingly nudging them to give immunotherapy a try.

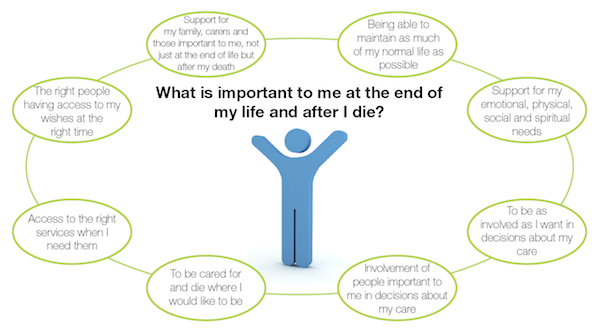

But that advice is now coming with unintended consequences. Doctors who counsel immunotherapy, experts say, are postponing conversations about palliative care and end-of-life wishes with their patients — sometimes, until it’s too late.

“In the oncology community, there’s this concept of ‘no one should die without a dose of immunotherapy,’” said Dr. Eric Roeland, an oncologist and palliative care specialist at University of California, San Diego. “And it’s almost in lieu of having discussions about advance-care planning, so they’re kicking the can down the street.”

Palliative care and oncology teams have long been wary of each another. For many oncologists, palliative care teams are the specialists to call in only when curative treatments have been exhausted. For many palliative care specialists, oncologists are the doctors who prescribe treatments without regard to quality-of-life considerations.

But the new collision between immunotherapy and palliative care experts comes at an inopportune moment for health care providers, who have in recent years promoted palliative care as a way to increase patient satisfaction while reducing costs associated with hospitalizations and emergency room visits.

Dr. Cardinale Smith, an oncologist and palliative care specialist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, said she has seen a handful of patients who tried immunotherapy treatments after failing chemotherapy, and who were later admitted to the hospital in poor condition. Almost all of them died there, without having been asked about where, and under what conditions, they might prefer to die.

“These conversations are not occurring because of the hope that this will be the miracle treatment,” Smith said. “Unfortunately, on the part of the oncologist, treatments like immunotherapy have become our new Hail Mary.”

Immunotherapies work for only around 15 to 20 percent of cancer patients who receive them.

They have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for Hodgkin lymphoma and certain cancers of the lung, skin, blood, kidney, bladder, and head and neck — but not for common cancers like prostates and most cancers of the colon and breast. A new type of immunotherapy, CAR-T, was approved earlier this week for leukemia.

But even for those cancers, oncologists and patients sometimes refuse to acknowledge clear signs that immunotherapies are failing, said Dr. Sandip Patel, a cancer specialist and immunotherapy researcher at the University of California, San Diego.

Patel said he now engages home-based palliative care specialists, who can provide supportive care while a patient’s health is relatively stable. “Then, at least when they transition to hospice, it’s not as much of a free fall out of the traditional health system, and if they’re one of the patients who respond to the therapy, great.”

He lamented the fact that patients who fail immunotherapy treatments spend more time in hospitals than with their families at home. “The flip side is, if I had a cancer with a 15 percent response rate, and if the benefit might be longer-term, I’d try it,” he said. “Who wouldn’t buy a ticket to a lottery of that importance?”

But not all patients have a clear idea of what that lottery ticket might cost them. Carrie Clemons’s father, Billy Clemons, who is 68 and is a former Texas state representative, last year stopped responding to chemotherapy for renal cell cancer that first struck him in 2002. His doctors recommended the immunotherapy Opdivo, which had recently been approved for his cancer.

At the time, he was symptom-free from his cancer, though scans showed it had spread to his lungs and some lymph nodes.

Two infusions of the drug, Clemons said, were followed by “eight months of hell,” during which her father became incontinent and had to use a wheelchair, lost his eyesight and most of his hearing and speech, and endured multiple weeks of intubation and care in the ICU. When his heart stopped beating, he needed to be resuscitated.

While immunotherapies trigger debilitating side effects much less frequently than chemotherapy, they can spur potentially life-threatening conditions, depending on the cancer type and the treatment approach. Fewer than 5 percent of patients overall face serious side effects, for instance, but more than one-third of melanoma patients who receive a combination of immunotherapy drugs can experience such conditions. The upside: Half of those melanoma patients will see their cancer shrink for at least two years.

Clemons’s doctors at Houston’s MD Anderson attributed the reaction to a runaway immune system that essentially attacked his central nervous system. To reverse it, he needed weeks of therapy to replace his plasma with that of donors, to clear away his blood’s overly active antibodies.

He slowly improved, though, to the point where only some slight vision impairment remains, and doctors recently declared his cancer in remission.

Although the family is thrilled at the outcome, Clemons said, they had little idea when they began that such side effects were possible, and doctors never engaged the palliative care team to either discuss side effects or help manage them.

She wouldn’t have known to ask about such care. “I always just equated palliative care with hospice,” she said.

Hospitals overall have made some headway in integrating oncology and palliative care specialists, with more oncologists referring patients to palliative specialists to help them ease side effects of treatments and achieve quality-of-life goals.But Roeland, the doctor at the University of California, and others say the integration is less smooth when it comes to cutting-edge cancer treatments.

Palliative care teams have not been able to keep abreast of the breakneck pace of cancer treatments, so they may not be offering up-to-date counsel to patients who ask about possibly life-changing therapies.

Meanwhile, most of the growth in palliative care medicine has happened among clinicians who work in hospitals, where they generally see only those who have done poorly on immunotherapies, for instance.

“They’re not seeing the super-responders,” Roeland said. “So their first reaction usually is, ‘Why would you do that?’”

Roeland understands more than most the seductive qualities of an eleventh-hour immunotherapy gambit. He had given up hope of curing Bernard “Biff” Flanagan, 78, of his esophageal cancer in late 2015, and referred Flanagan to hospice care to help him manage his extreme weight loss, fatigue, and the emotional distress he felt from not being able to swallow.

But Flanagan, who speaks with the gruff, seen-it-all humor one might expect from a career FBI agent in LA, wanted to keep seeking a cure.

Roeland said he knew that many hundreds of clinical trials were testing the therapies on other cancers, so he did some digging. A paper from a recent cancer conference showed that some people with squamous cell esophageal cancer responded to immunotherapy. He could arrange to get the drug through the Bristol Myers Squibb, for free.

He presented the idea to Flanagan and his wife, Patricia, with the caveats that it might not work, and could come with possibly significant side effects.

Flanagan jumped at the chance. Patricia, a former professional photographer, was less enthused.

“I ran into her later in the coffee shop,” Roeland said. “She looked at me like. ‘What the hell are we doing here? He doesn’t have a good quality of life.’ I’m feeling guilty now.”

Roughly six weeks into the treatment, Flanagan’s energy was returning, and he found himself at the fridge. “I grabbed a glass of OJ, knocked it down, swallowed it no problem,” he said. “And it was like a miracle. I had another one.”

Now Flanagan has no symptoms, and he experienced only the briefest side effect: a skin rash that abated with ointment. Patricia recently helped him dispose of the morphine and other medications the hospice team had given them.

“If he’d died in the hospital, I would’ve felt terrible,” she said. “If I were in his place at that point, I’d have tried to arrange to die at home at my own choosing, but Biff just didn’t have as strong feelings about that as I had.

“I had little hope that he was going to recover, but it’s just been amazing. He really is living the life he’s always lived.”

Roeland said that for the experience “is so immensely rewarding that it drives an oncology practice. It can be 1 in 100 that happens like that, and you say, well, is it worth it?”

Complete Article HERE!