By Denyse O’Leary

Anthropologist Barbara J. King, author of How Animals Grieve (2014), has written a thought-provoking essay on the difficulties that COVID-19 has created for people coping with the death of a loved one because they are not allowed conventional grieving methods. Although it is titled “Animal Grief Shows We Aren’t Meant to Die Alone,” King’s essay turns out to be appropriately skeptical of ambitious claims about animal grief. She writes,

There is a popular perception that some animals, particularly elephants and crows, participate in their own kinds of funerals. But there’s little solid evidence—at least, so far—for this kind of community ritual. Elephants may occasionally cover a dead companion’s body with leaves or branches, but the meaning and intent of this action remains unclear. A 2012 paper includes the words “scrub-jay funerals” in the title, but the “funerals” were actually noisy gatherings of birds around scrub-jay skins and feathers laid out by researchers in an experiment. The birds’ response to what they saw indicates acute social assessment of their surroundings, to be sure, but it’s a stretch to consider that behavior a death ritual.

Barbara J. King, “Animal Grief Shows We Aren’t Meant to Die Alone” at Sapiens (April 22, 2020)

That said, she cites a number of instances of animals showing apparent grief at the death of a companion:

At the Farm Sanctuary in New York state, after years of close companionship, a duck named Harper withdrew socially and refused to form new bonds after the death of his duck friend Kohl in 2010.

Barbara J. King, “Animal Grief Shows We Aren’t Meant to Die Alone” at Sapiens (April 22, 2020)

But wait; it’s hard for a human to be sure what’s happening here. Harper may simply have lost the ability to form close bonds with other ducks, irrespective of what, if anything, he understands about Kohl’s absence. Again, while much is made of primates grieving over dead companions,

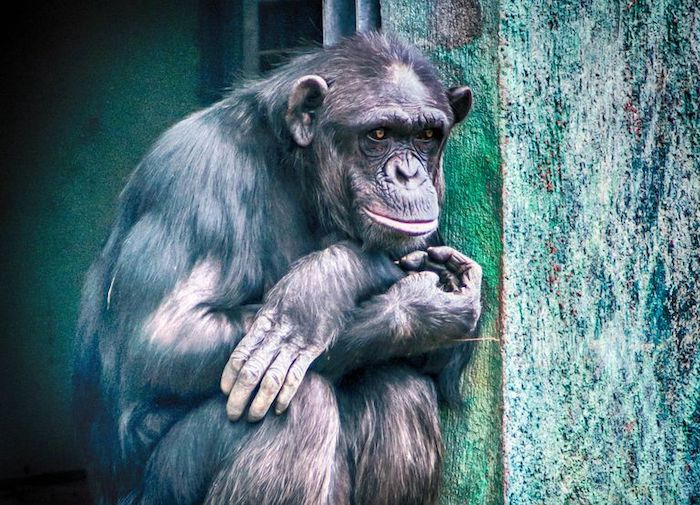

Monkeys and apes don’t act exactly as humans do around dead bodies. Mixed in with compassionate caretaking may be aggressive or even sexual behaviors: They might strike or mount a corpse. Yet human grief, too, can manifest in unusual ways. At a solemn memorial service, a mourner may suddenly laugh in involuntary response to tension.

Barbara J. King, “Animal Grief Shows We Aren’t Meant to Die Alone” at Sapiens (April 22, 2020)

Well, we are beginning to get a clue now. A human being may behave oddly at a funeral but that is because of an awareness of what death means. The monkey is troubled by death but does the monkey understand what death is? Anthropologists like King resist making that distinction:

For much of the 20th century, it was common practice for ethologists to resist acknowledging the profound emotions expressed by these animals. Anthropologists and zoologists who broke with tradition to describe animal grief—and other emotions as well, including joy—found themselves accused of anthropomorphism, the projecting of human capacities onto other species. The tide began to turn, however, as ever-more research in the field and in captivity showed unmistakable evidence of animals feeling deeply what happens to them. More than ever before, researchers now recognize that grief and love don’t belong only to us humans.

Barbara J. King, “Animal Grief Shows We Aren’t Meant to Die Alone” at Sapiens (April 22, 2020)

No, love and grief don’t belong only to us humans. But there is something that does. Consider the story of Hachikō, the Akita dog (right, in 1934) whose human friend, a professor named Hidesaburō Ueno, died of a cerebral hemorrhage while on a train trip in Japan in 1925 and never returned to the station from which Hachikō had seen him go:

Hachiko moved in with a former gardener of the Ueno family. But throughout the rest of his ten-year-long life, he kept going to the Shibuya Train Station every morning and afternoon precisely when the train was due to enter the station. He sat there for hours, patiently waiting in vain for the return of his beloved owner which sadly never came back.

Maria Wulff Hauglann, “The Amazing And True Story Of Hachiko The Dog” at Nerd Nomads

Hachikō has inspired much devotion ever since, along with several films and monuments.

The touching part of the story is not simply Hachikō’s devotion but the fact that the dog could not know that his beloved Hidesaburō had died.

Death, after all, is an abstraction. We can be told that someone has died and, without seeing the person’s body, we know what that means. We also know that all human beings (and all animals) will die sometime. But that is an abstraction too. For humans, mourning is a philosophical as well as an emotional affair. As a result, death raises questions about the meaning of life which Harper, the monkeys, and Hachiko could never ask.

It is these thoughts and questions, not only grief, that have always underlain funerals:

What’s undeniable is that our early Homo sapiens ancestors began to create increasingly elaborate burial rituals. At around 24,000 years ago in what is today Sunghir, Russia, for example, a boy of about 12 years of Animals ranging from elephants to cows, ducks to dogs, may grieve.age and a girl of about 9 were buried together. The research paper describing the remains says they were “head to head, covered by red ocher, and ornamented with extraordinarily rich grave goods.”

Barbara J. King, “Animal Grief Shows We Aren’t Meant to Die Alone” at Sapiens (April 22, 2020)

But then those human beings knew what it meant in the abstract to say that the children had died. The grave goods they provided suggest that the mourners thought the children might need something somewhere. But they surely understand that somewhere to be another dimension of reality. That’s part of what the animal doesn’t have.

So do animals grieve? Yes indeed. Do they grieve the same way humans do? No, because, for better or worse, they can’t. There is no turning back from the gift of reason.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!