Diane Rehm “brings a level of reason and sanity to this discussion that is severely lacking when you look at the opponents of death with dignity,” said Howard Ball, a University of Vermont political scientist. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

Diane Rehm “brings a level of reason and sanity to this discussion that is severely lacking when you look at the opponents of death with dignity,” said Howard Ball, a University of Vermont political scientist. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)Diane Rehm and her husband John had a pact: When the time came, they would help each other die.

John’s time came last year. He could not use his hands. He could not feed himself or bathe himself or even use the toilet. Parkinson’s had ravaged his body and exhausted his desire to live.

“I am ready to die,” he told his Maryland doctor. “Will you help me?”

The doctor said no, that assisting suicide is illegal in Maryland. Diane remembers him specifically warning her, because she is so well known as an NPR talk show host, not to help. No medication. No pillow over his head. John had only one option, the doctor said: Stop eating, stop drinking.

So that’s what he did. Ten days later, he died.

For Rehm, the inability of the dying to get legal medical help to end their lives has been a recurring topic on her show. But her husband’s slow death was a devastating episode that helped compel her to enter the contentious right-to-die debate.

“I feel the way that John had to die was just totally inexcusable,” Rehm said in a long interview in her office. “It was not right.”

Diane Rehm and her late husband, John Rehm, wrote a book about their marriage. John died last year after suffering from Parkinson’s disease. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

Diane Rehm and her late husband, John Rehm, wrote a book about their marriage. John died last year after suffering from Parkinson’s disease. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)More than 20 years after Jack Kevorkian jolted America with his assisted-suicide machine, Rehm is becoming one of the country’s most prominent figures in the right-to-die debate. And she’s doing so just as proponents are trying to position the issue as the country’s next big social fight, comparing it to abortion and gay marriage. The move puts Rehm in an ethically tricky but influential spot with her 2.6 million devoted and politically active listeners.

Now 78 and pondering how to manage her own death, Rehm is working with Compassion & Choices, an end-of-life organization run by Barbara Coombs Lee, a key figure in Oregon’s passage of an assisted-suicide law and a previous guest on the show. Rehm will appear on the cover of the group’s magazine this month, and she is telling John’s story at a series of small fundraising dinners with wealthy donors financing the right-to-die campaign.

If asked, she said she would testify before Congress.

Rehm’s effort comes less than a year after Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old woman suffering from terminal brain cancer, moved to Oregon to legally end her life, giving the issue a new spin. That she was young and beautiful helped proponents broaden their argument, making the case that it is a civil right, not just an issue for graying Baby Boomers.

Brittany Maynard was 29 when she died in Oregon last year. She had brain cancer and moved to Oregon because of the state’s death with dignity law. (AP)

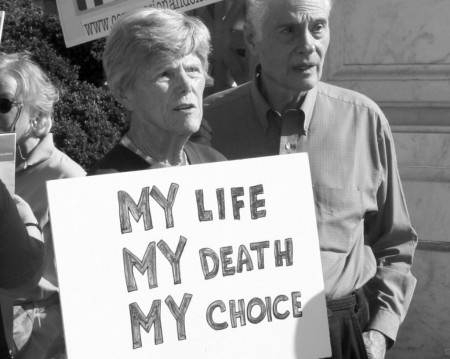

Brittany Maynard was 29 when she died in Oregon last year. She had brain cancer and moved to Oregon because of the state’s death with dignity law. (AP)The Maynard case prompted a surge of activity among state lawmakers pursuing so-called death-with-dignity laws, including in Maryland, New York, Florida, Kansas, Wisconsin and the District. Progressive politicians and voters say the country is ready for the conversation.

“Kevorkian was before his time,” Rehm said. “He was too early. The country wasn’t ready.”

Public opinion on the issue depends on how it is described, according toGallup, which has found strong support for doctors helping patients end their lives “by some painless means,” but a far slimmer majority in favor “assisting the patient to commit suicide.” Not surprisingly, groups such as Compassion & Choices studiously avoid using the word suicide.

Laws granting the right to die exist in only three states — Oregon, Washington and Vermont. New legislation faces staunch opposition from religious groups and the medical establishment.

In Massachusetts and other states where legislation has failed, proponents faced well organized public campaigns from the Catholic church, whose American bishops call suicide a “grave offense against love of self, one that also breaks the bonds of love and solidarity with family, friends, and God.”

Pushback from the American Medical Association has been equally fierce, with the organization saying that “physician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer, would be difficult or impossible to control, and would pose serious societal risks.”

Both sides of the debate see Rehm’s entry into the debate as an important development.

“She brings gravitas, she brings her experience and she brings a level of reason and sanity to this discussion that is severely lacking when you look at the opponents of death with dignity,” said Howard Ball, a University of Vermont political scientist and author of “At Liberty to Die: The Battle for Death with Dignity in America.”

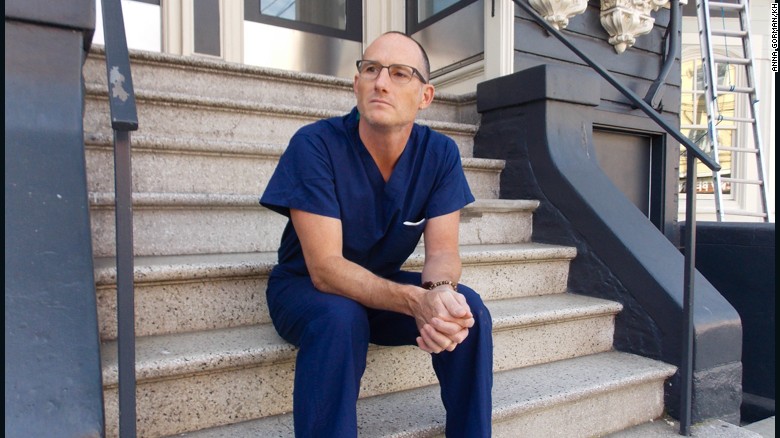

Ira Byock, a palliative care physician and vehement opponent of assisted death, has argued against the movement on Rehm’s show. Though he credits her for having him on, he said her story and influence distracts from the conversation the country should be having about improving end-of-life care.

“It sucks all of the oxygen out of the room,” he said.

‘I don’t want comfort’

They met in 1958. John was a lawyer at the State Department. Diane was a secretary.

“Physically, she was a knockout,” John wrote in a book they published about their marriage. But there was more. “It became clear, for example, that Diane had a fierce intellectual curiosity.” She never went to college, but had a copy of “Brothers Karamazov” on her desk.

Diane recalled his crew cut, his physique, his own intellectual curiosity.

“We loved taking long drives into the countryside,” Diane wrote, “and then going out for pizza and wine at Luigi’s, talking about our dreams, our fantasies, our attraction to each other.”

They wed and had two children, but marriage wasn’t as easy as falling in love. John was a loner, a workaholic. Diane was more outgoing, centered on family. They disagreed about so many things, nearly breaking up.

One thing they agreed on: Death.

“We had both promised each other we would help each other when the time came,” Diane said, “if there was some incurable or inoperable disease.”

The end of John’s battle with Parkinson’s last June was that moment. They had a meeting with his doctor. Their daughter, Jennifer Rehm, a physician in the Boston area, listened on the phone. She said, “Dad, they can make you comfortable.” Her father replied: “I don’t want comfort.”

The doctor made it clear he couldn’t help, but offered the self-starvation option, which the Supreme Court has ruled legal. John, living in an assisted-living community, didn’t immediately make the decision. The next day, Diane went to visit.

“I have not had anything to eat or drink,” he told her. “I have decided to go through with this.”

“Are you really sure?” Diane asked.

“Absolutely,” she said he told her. “I don’t want this.”

Diane stayed by his bedside. A couple days later, he went to sleep, aided by medication to alleviate pain. She read to him, held his hand, and she prayed.

“I prayed and prayed and prayed to God, asking that John not be suffering in any way as his life was ebbing,” she said.

Like his wife, John was Episcopalian, a church that has passed a resolution against assisted suicide and active euthanasia. She didn’t think God minded very much.

“I believe,” she said, “there is total acceptance in heaven for John’s decision to leave behind this earthly life.”

As John edged closer to death and the end of their 54-year marriage, a priest friend came to visit. Diane got a glass of red wine for a service of Holy Communion next to her husband’s bed. She put a drop of red wine on his lips. The priest performed last rites.

She spent the night with him, and in the morning she went home for a quick shower. Then she received a call — come fast, he’s slipping away. She missed his death by 20 minutes. She is still angry about that. If he could have planned his death, she and his family would have been there.

“That’s all I keep thinking about,” she said. “Why can’t we make this more peaceful and humane?”

John donated his body to George Washington Medical School. At his memorial service, some 400 people packed St. Patrick’s Episcopal Church — journalists, academics, policy makers and religious figures, including Marianne Budde, bishop of the Washington Episcopal Diocese.

Diane returned to work not long after. She told her producers she wanted to do another show on assisted dying.

It wasn’t until the last few minutes that Rehm told listeners what her husband had done: “John took the extraordinarily courageous route of saying, ‘I will no longer drink. I will no longer eat.’ And he died in 10 days.”

Richard from Florida called in. “You have my deepest sympathies and empathies with the loss of your husband,” he said. And then: “I’ve got to get to the state that gives me the choice.”

Rehm said she knows that as a journalist, she must be careful.

Diane Rehm, right, during “The Diane Rehm Show” at WAMU-FM in Washington.. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

Diane Rehm, right, during “The Diane Rehm Show” at WAMU-FM in Washington.. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)“As strongly as I feel, I don’t want to use the program to proselytize my feelings,” she said. “But I do want to have more and more discussion about it because I feel it’s so important.”

Sandra Pinkard, Rehm’s producer, said she appeals to listeners, in part, because she is so open about herself. She and John discussed their marriage on the air. She detailed his struggles with Parkinson’s.

Rehm came back to the assisted death topic in late October after Brittany Maynard announced plans to end her life.

Byock joined her on the show, knowing, he said, that “on this issue, she is clearly an advocate.” Though she didn’t mention her husband, he said he had to be “very assertive” to counter the focus on Maynard’s undeniably dramatic case.

Still, he said he would go back on the program “in a heartbeat” because it’s becoming a forum for the debate.

“It’s people like her listeners that I want to talk to,” he said. “I am sincerely grateful for giving me access to her listeners.”

Her last moments

They still talk, Diane and John.

“I miss you so much,” she’ll say out loud, alone in her apartment. When President Obama awarded her the National Humanities Medal last year, she told John, “It just breaks my heart you weren’t there.”

She could hear his voice: “Don’t worry, I’m there.”

Wherever he is, Rehm has plans to join him. But she doesn’t intend to die the way he did. Shortly after John’s funeral, Rehm made an appointment with her doctor to talk about her death.

“You have to promise,” Rehm told the doctor, “that you’ll help me.”

The doctor, Rehm said, was “receptive” to the request. “I think over a period of time he or she would provide me, if I were really sick, with the necessary means,” she said.

Rehm can’t fathom being in the “position where someone has to take care of me. God forbid I should have a stroke, I want to be left at home so I can manage to end my own life somehow. That’s how strongly I believe.”

Like John, she is donating her body to GW medical school. Once students finish learning from her remains, her family will take her ashes to the family’s farm in Pennsylvania, spreading them near the same hickory tree that shades John’s ashes.

Rehm can vividly see her last moments. She is in her bed, at her home, unafraid.

“My family, my dearest friends would be with me holding my hand,” she said. “I would have them all around me. And I would go to sleep.”

Complete Article HERE!

The laws would allow mentally fit, terminally ill patients age 18 and older whose doctors say they have six months or less to live to request lethal drugs.

The laws would allow mentally fit, terminally ill patients age 18 and older whose doctors say they have six months or less to live to request lethal drugs.