— Conversations about end-of-life issues are difficult for everyone. But in many cultures, these important topics are considered almost taboo to discuss.

“Death and dying are not topics normalized to openly talk about, especially among Asian families,” says Chrislyn Choo, 29, of My China Roots, a genealogy startup.

“There’s often denial about getting older and end of life or flippant comments attached to shame [with] comments like, ‘You’ll wish you listened to me when once I’m gone.'”

For these reasons, Holly Chan and Elizabeth Wong founded Death Over Dim Sum, a workshop series geared toward opening up intergenerational dialogues about life, death and beyond.

Why Dim Sum?

Wong, 48, has been a labor and delivery nurse for over 20 years. Wong says, “My role as a nurse working with birth doulas who offer comfort and support at the beginning of life made me wonder why there wasn’t a similar doula-type role in helping people as they get older and transition through the end-of-life.”

“There’s often denial about getting older and end of life or flippant comments.”

Wong did some research and discovered that there were, in fact, end-of-life-doulas,” so she trained to become one, later co-founding Beacon Light Doulas. As a Doulagivers training partner, she set up a Facebook page to spread word about their programs, which is how she met Chan.

Chan, 29, a user experience designer in Seattle, explains, “I have been passionate about design innovations in the funeral industry and end-of-life care since I was in high school. While I was living in San Francisco I stumbled onto Elizabeth’s page and followed it. Elizabeth messaged me and we started chatting online.”

The two decided to meet over coffee. They found that despite their different upbringings, they still had much in common when it came to their experiences as second-generation Chinese American women.

The two began brainstorming on how they could work together. Their conversations led to the creation of Death Over Dim Sum. The first workshop was held in 2019 at the End of Life Festival hosted by Reimagine in San Francisco.

They gathered six local experts — Wong among them — on various topics including palliative care, funeral arrangements and financial planning. Frank Chui, the owner of Hang Ah restaurant in San Francisco, agreed to donate the food.

While it may seem odd to talk about heavy topics while enjoying fried rice and dumplings, the two believe it is an ideal combination. “In my family, we often talk over food because it’s easier to handle tough conversations when our bellies are warm and full,” explains Chan.

“From personal experience, I found dim sum is often a comfort food in Chinese American families, so what better way to bring people together to talk about a taboo subject than over a delicious meal?”

Creating a Comfortable Environment

Both Wong and Chan wanted to ensure an open conversation where all participants would feel safe expressing themselves. Although not mandatory, Wong and Chan do prioritize inviting bilingual subject matter experts who identify as Asian or Pacific Islander.

“I grew up in Chinatown, highly immersed in Chinese culture and surrounded by first-generation immigrants, many of whom spoke limited English. It’s important that participants can relate to the experts, understand the information presented and be comfortable asking questions.”

Because it can be difficult just knowing how to start the conversation, Wong and Chan modeled the workshop’s structure after a traditional dim sum service. “Typically, dim sum involves picking out what food you want to eat from carts being pushed around a busy restaurant,” explains Chan.

“It’s important that participants can relate to the experts, understand the information presented and be comfortable asking questions.”

“At the beginning of the workshop, participants pick up a ‘menu’ of frequently asked questions, divided by subject matter. They are encouraged to check off what questions they would like to ask the experts, but unlike at a restaurant they are also encouraged to order ‘off menu’ with their own questions.”

James Liu, a Healthcare startup founder in San Francisco, attended the second Death Over Dim Sum in March 2023. He returned for the third workshop, but this time as a volunteer. Liu was pleasantly surprised by the casual and approachable nature of the event.

Liu says, “I appreciated the breadth of the speakers and the topics covered, mixing in both practical topics, such as planning a funeral and what legal documents are required, to the more emotional and spiritual, like the goals of care conversations and navigating family dynamics.”

Different Reasons to Attend

Thanks to a grant from San Francisco Palliative Work Group, Wong and Chan have been able to hold three workshops since their inaugural event.

Currently their workshops have only taken place in the San Francisco area but they hope to expand them to Seattle and beyond in the future.

“They helped us face our fear, like ‘Let’s talk about death and dying so they no longer scare or paralyze us.'”

Participants in the workshops have ranged in age, background and reasons for attending. Choo lives with her aunt who is in her 60s so they attended a workshop together in March 2023. “Holly and Elizabeth created a helpful, safe space for intergenerational conversation,” says Choo. “The atmosphere was serious but not intimidating. They helped us face our fear, like ‘Let’s talk about death and dying so they no longer scare or paralyze us.'”

Dyanna Volvek, 39, of San Francisco attended a workshop in March 2023. She explains, “My partner and I have decided not to have children. People often ask me, ‘If you don’t have children, what will you do when you get older? Who will take care of you and your husband?’ I explain that just because you have children doesn’t mean they will take care of you. But these questions got me thinking about what I would do when I am older and my parents age, so I decided to attend the workshop.”

Taking Care of Elders

In Chinese families, it is common practice for multiple generations to live together with the expectation that they ultimately become older relatives’ caretakers. Wong explains, “My mother, like many in our community, immigrated to America for a better life. Our parents and grandparents made sacrifices for us, and when they age, we feel it is our responsibility to do the same for them.”

“Our parents and grandparents made sacrifices for us, and when they age, we feel it is our responsibility to do the same for them.”

This feeling of responsibility can be daunting. “I feel guilty that I might not be able to care for my parents or grandparents due to financial constraints,” explains Volvek. “It was helpful to be surrounded by other people who understood my feelings due to our shared cultural upbringing.”

Anni Chung, President and CEO of Self Help for the Elderly was an expert at two Death Over Dim Sum workshops. Chung says, “Many of the second-generation adults have moved out of the area due to high rents or new work opportunities since Covid. But their elderly relatives may be stuck here. They need to know how to help their loved ones from a distance such as how to choose a facility or how to find a local bilingual caretaker.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The Palliative Path

— A meditation on dignity and comfort in the last days of a parent’s life

By Abeer Hoque

In 2020, in the midst of a worldwide pandemic, my 85-year-old father suffered a heart attack in Pittsburgh and was rushed to the hospital.

The stent, a minorly invasive procedure, was the easy part.

But the two days he spent in UMPC’s state-of-the-art ICU were a nightmare. The anesthesia made him groggy and aggressive. The sleep meds made him perversely restless and short of breath. The IV he constantly fiddled with, once even ripping it out, much to our horror.

Instead of restraining him, which I imagine to be a cruel and unusual punishment for an Alzheimer’s patient, the ICU staff let me stay with him overnight (a massive kindness made greater by the strict Covid protocols of that time). This way, I could keep him from wandering, from pulling out the IV, from being confused about where and why and what. Every two minutes—I timed it, and it was comically on the clock—I explained and comforted and explained again. By midnight, I thought I would go mad with worry and exhaustion. By 3 a.m., I was seeing stars, my father and I afloat in an endless hallucinatory universe of the now. By 6 a.m., we were both catatonic.

After he came home, my father was in a bad state. Physically he was fine, if a bit unsteady, but emotionally, he was depressed, anxious, raging, unresponsive. His appetite was out of control and he raided the fridge at all hours. He barely slept, wandering the house like a ghost of himself. It took almost three months for him to return to his ‘normal’—another immense gift from the universe, as medical crises often spell inexorable decline for the elderly.

A year later, the doctors discovered a giant (painless) aneurysm in his stomach, which could rupture and kill him “at any moment”.

Operating would mean a five-inch incision, at least five days in the ICU and up to a year to recover fully (if at all). For someone with dementia, major surgery also seemed a cruel and unusual punishment. From New York to Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, my siblings, my mother and I met over video chat to discuss at length. We made the difficult decision to let the aneurysm be, to keep my father comfortable and at home.

Initially, my mother felt tortured. Were we giving up on my father? Was she abdicating her responsibility?

These are questions that modern medicine is not always fully equipped to answer.

Doctors (especially surgeons) are often focused on finding and fixing the physical problem. But Alzheimer’s is a uniquely mental condition and it forced us to consider my father’s health and well-being on more than just the physical front. We wanted to prioritise his dignity, his comfort, his pain-free state: namely, his overall quality of life.

Days later, the doctors told us that the aneurysm was actually inoperable because of its position in his body. Moreover, there were two rogue blood clots that, if disturbed, could travel to the brain and kill him instantly. Our decision had been the right one, not just mentally but also medically.

Our family made another big decision at this time: we would not take my father to the hospital anymore—instead we would start palliative care.

I have been recommending Atul Gawande’s brilliant book Being Mortal to everyone since I read it five years ago. It lays out the case for palliative medicine (a.k.a. hospice care) in compelling detail. Instead of trying to prolong life, palliative care prioritises a patient’s physical and mental well-being and focuses on pain management. Not only does this kind of care drastically reduce the chances of family members developing major depressive disorder, but the patient outcomes are astonishing:

Those who saw a palliative care specialist stopped chemotherapy sooner, entered hospice far earlier, experienced less suffering at the end of their lives—and they lived 25% longer. If end-of-life discussions were an experimental drug, the FDA would approve it.

Atul Gawande, in his book ‘Being Mortal’

In February 2023, my parents moved to Dhaka after 54 years abroad (in Libya, Nigeria and the States), abandoning the isolating, exorbitant, often neglectful care networks of America for the familial support and affordable at-home caregiving of Bangladesh. We were privileged to have this option, to have extended family so loving and helpful, to have enough money to pay rent and hire multiple caregivers.

For my mother, who had been my father’s full-time caregiver for over a decade, it was a new lease on life, letting her visit childhood friends, walk in Ramna Park every morning, get a full night’s sleep. We were additionally lucky that over 10 months, we did not have to see a doctor because my father’s occasional tummy upsets and falls did not result in serious illness or injury.

In December 2023, my mother left for the US for five weeks to visit my sister and her three children and to hold her newest month-old grandchild (my brother’s first child) in her arms. It would be the first time in more than a decade that she would leave my father for more than a few days, and she agreed to this vacation only because I had taken an extended break from my life in New York to be in Dhaka while she was away.

Three days after she landed in Pennsylvania, my father suffered his first medical crisis in over a year: a distended belly and extreme stomach pain.

I immediately called my cousins who live down the street. Two of them brought over their mother’s doctor, a young generalist who worked in the ICU of the hospital around the corner from us in Bonosri. Seeing my father’s taut and grossly swollen stomach, the doctor advised urgent hospitalisation. Thus started a gruelling, repetitive, exhausting conversation about palliative care, all while my father cried out in pain from the bedroom.

Despite several palliative and hospice centres in Dhaka, the concept seems unknown to many Bangladeshis, perhaps even heartless.

Neither of my cousins could sleep that night after hearing my father’s cries. I explained why we had decided against hospitalisation, against X-rays, ultrasounds and blood tests, against antibiotics and IV-administered fluids. I predicted that the hospital would likely have to restrain or sedate him or both. I said that even if we eased his physical state, mentally he would be traumatised.

This resistance to palliative care is not uniquely Bangladeshi. Families across the world are torn apart because family members have different ideas on how to best take care of a loved one. Too often, no one has asked the patient their preferences about resuscitation, intubation, mechanical ventilation, antibiotics and intravenous feeding. Too often, it’s too late to ask by the time these medical interventions come into play.

The doctor finally offered pain and gastric medicine via intravenous injections. One bruised wrist later, my father was more comfortable. Over the next 24 hours, he had two more injections, but by the third one, the pain meds were no longer working.

At 2 a.m. on a cool Dhaka winter night, we levelled up, the doctor generously taking time off his night shift to come to our house with a nurse and administer an opioid that eased the pain for another day and half.

By Christmas, or Boro Din as they call it in Bangladesh, I had defended palliative care more than half a dozen times to my relatives, each one aghast at how my father could suffer so, without my helping, i.e., hospitalising him.

This then was my struggle: to remember I was not there to fix anything, but to ensure that he remain in familiar surroundings, in his sunny airy bedroom. That he not be in pain.

This too was my struggle: to get my extended family on board with palliative care.

The cousin who came to live with us in America when he was in high school and who idolised my parents. The cousin who asked me to bring my father’s nice shirts and blazers from Pittsburgh so he could wear them. Their sweet wives, my bhabis, and their lively loving children who visited my father almost every day. To hold back my kneejerk reactions:

Are they questioning my family’s judgement? Is this the patriarchy at work? Do they understand that it is no easier for me to see my father in pain?

My challenge was to set my defensiveness aside and try to infuse their love and concern with knowledge and perspective, so they could help me help my father spend his remaining days in comparative ease, rather than more aggressive medical treatment.

My last struggle was the hardest of all: The one that questioned the kind of life my father had been living these last few years.

Nine years after his Alzheimer’s diagnosis, he could not do a single thing that used to bring him pleasure: dressing nicely each morning, making himself breakfast while exclaiming over the newspaper headlines, reading history books and novels, writing fiction in Bangla, teaching geology in English, wandering the Ekushay February book fair, visiting his ancestral home in Barahipur, playing cards and watching action films, making his grandchildren collapse into giggles, walking on the deck at sunset with Amma, holding court with the Bangladeshi community in Pittsburgh, speaking to his two beloved remaining siblings, my Mujib-chacha and Hasina-fupu, delighting my mother with his quick-witted jokes.

If he could make no new memories and the only joys he had were fleeting—the chocolate chip cookies from Shumi’s Hotcakes, my mother’s smiling face, his caregivers’ tender ministrations—were these enough?

Was there some Zen-level lesson here on living in the moment?

And when these brief moments were interleaved with longer troubling periods of confusion, distress, rage and sadness… What then?

What about the endless hours spent restless and awake, his eyes lost and searching?

My father and I had had a fraught relationship my whole life.

Patriarchal and emotionally distant, he threw me out on several occasions, literally and figuratively. I didn’t speak to him for years at a time, and even reconciled, our exchanges were limited to politics, education and writing. He seemed uninterested in anyone’s emotional life, unable to engage in conflict without judgement and anger. His gifts of intellectual brilliance, iron-clad willpower and moon-shot ambitions did not make him an easy father—or easy husband, for that matter.

But now, none of that mattered. The only thing that did was my attempt to attend to him with kindness.

Linking his dementia-fueled rage to his life-long habitual rage would make the already difficult task of caregiving impossible. I had read enough studies that showed that caregivers died earlier because of their stress. It wasn’t hard to see the toll it had taken on my mother over the years. She had been hospitalised for rapid heartbeat issues twice last year and, despite a lifetime of healthy living, had developed high blood pressure to boot.

In his sleep-deprived, pain-addled state, my father didn’t always respond or recognise those around him. But one night, in a moment of lucidity, he reached for my hand and asked urgently, “Are you doing ok?”

“Yes Abbu,” I assured him, “I’m doing fine.”

And then he said—faint, incomplete, clear—“Take… your Amma.”

I said, “Of course I will.”

He was telling me what I’d always known, that despite everything, he had always looked out for my health and self-sufficiency, and more importantly, that looking after my mother was our shared act of service.

If this winter of struggle and sorrow gave my mother more time in the world, then I was ready for it. Would that the path were palliative for us all.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Why You Should Consider a Death Doula

— End-of-life doulas are compassionate and knowledgeable guides who can walk with you through death and grief.

We’re all going to die, and before that, we will probably navigate the deaths of several people we love along the way.

Too dark? Discomfort with the idea of death may be the reason that people rarely talk about it, plan for it, or teach each other how to cope with it.

“Many people in our society are death phobic and do not want to talk about it,” said Marady Duran, a social worker, doula, and educator with the International End-of-Life Doula Association. “Being an end-of-life doula has been so much more than just my bedside experiences. I am able to talk with friends, family, and strangers about death and what scares them or what plans they have. Being a doula is also about educating our communities that there are many options for how end-of-life decisions can be made.”

When you or a loved one inevitably faces death, there can be an overwhelming feeling of What do I do now? What do I do with these feelings… and all this paperwork? End-of-life doulas (also called death doulas or death coaches) are compassionate and knowledgeable guides who can walk with you through death and grief.

The experience of supporting a childhood friend through her death at the age of 27 motivated Ashley Johnson, president of the National End-of-life Doula Alliance, to commit herself to this role.

“Walking alongside her during her journey, I recognized the tremendous need for education, service, and companionship for individuals and their families facing end-of-life challenges,” Johnson said. “The passing of my dear friend only solidified my commitment to this path. I saw it as my calling to extend the same level of care and support to others who were navigating the complexities of end-of-life experiences. I firmly believe that every individual deserves the dignity of a well-supported end-of-life journey, and that starts with demystifying the process, reducing fear, and helping families achieve the proper closure they need to heal.”

What to expect from a death doula

The services provided by an end-of-life doula are actually pretty varied and flexible. Much like birth doulas, they do not provide any medical care. These are some of the services Johnson said she provides in her work:

- Advance health care planning. This might include a living will, setting up durable power of attorney for health care, and advance directive decisions. “We help individuals and their families navigate the complex process of advance healthcare planning, ensuring their wishes and choices are respected and documented,” Johnson said.

- Practical training for family caregivers. End-of-life doulas can teach caretakers and family members how to physically care for their loved ones as they near death.

- Companionship to patients. “We provide emotional support and companionship to patients, helping to ease their feelings of isolation and anxiety,” Johnson said.

- Relief for family caregivers. Caring for a dying family member can be relentless, but caregivers need time to step away and care for themselves too.

- Creating a plan for support at the patient’s time of death. A person nearing the end of their life may be comforted by many things in their environment, from the lighting, music, aromatherapy, and who’s present. A doula can help coordinate all the details.

- Grief support. “Our role extends into the grieving process, offering support to both the dying person’s loved ones and the patient during the end-of-life journey and beyond,” Johnson said.

- Vigil presence for actively dying patients. “We ensure that no one faces the end of life alone by being a comforting and compassionate presence during the active dying process,”Johnson said.

- Help with planning funeral and memorial services. Planning services is a complicated task to tackle while you are likely exhausted with grief. Doulas have been through this process many times and can be a steady hand while you make decisions.

“Our aim as death doulas is to enhance the quality of life and death for all involved,” Johnson said. “We provide a range of non-medical support, fostering an environment where individuals and their loved ones can find comfort, guidance, and a sense of peace during this profound and delicate phase of life.”

When is it time to bring in a doula?

Death doulas can provide comfort and support to both the dying person and their loved ones at any stage of the process. They can step in to help before, during, or after a death.

- At any time, before you even receive a terminal diagnosis, doulas can help you prepare emotionally and practically with planning for end-of-life wishes, advance care planning, and creating a supportive environment.

- During the end-of-life phase, doulas are more present to offer emotional, spiritual and practical support. They may be available weekly or daily, as needed.

- After death, doula services continue for the family of the deceased.

“There really is no timeline for grief,” Duran said. “Some will want to meet one or two times after the death, and some do not want to do grief work at all. It is a personal journey, and some people may take years to do the work.”

Support for an unexpected death

Not all deaths come with an advanced warning or time to prepare and plan. Even in the case of an unexpected death, an end-of-life doula can help you handle practical details and process grief. They can:

- Provide emotional support

- Help you understand the grief process

- Teach you coping strategies

- Help with arrangements, legal, and financial matters

- Help you create meaningful memorial rituals to honor the deceased

- Provide connection and community

- Listen and validate your feelings

- Provide long-term support

“My mentor Ocean Phillips, who is also a doula, always reminds me that ‘grief is another form of love,’” Duran said. “Grief gets a bad rap, and many people do not want to feel grief, but it can be transformative for many who experience it. People who go through an unexpected death of a loved one may feel guilt—‘If only I…I could have…’ The doula can hold space for them and allow them to share that. We can never fix or change, but we can stand with them and provide loving kindness along the way.”

Other professionals to help you navigate a death

Death doulas work in conjunction with many other professionals, including healthcare workers and hospice staff, to help families go through the process of death and all that follows.

“The whole team has a piece in being able to connect with those navigating grief and death. I always recognize that I am just one small part of the larger community that will help support those facing death and loss,” Duran said.

These are a few other professionals you might want to reach out to when facing the death of a loved one:

- Grief counselor

- Social worker

- Chaplain

- Community leaders

- Estate planning lawyer

- Probate lawyer

- Funeral service professional

- Financial planner

- Tax accountant (to help you file on behalf of the deceased and the estate)

- Estate liquidator or clean out-service.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

‘Financial Ruin Is Baked Into the System’

— Readers on the Costs of Long-Term Care

Thousands of people shared their experiences and related to the financial drain on families portrayed in the Dying Broke series.

By Jordan Rau and Reed Abelson

Thousands of readers reacted to the articles in the Dying Broke series about the financial burden of long-term care in the United States. They offered their assessments for the government and market failures that have drained the lifetime savings of so many American families. And some offered possible solutions.

In more than 4,200 comments, readers of all ages shared their struggles in caring for spouses, older parents and grandparents. They expressed their own anxieties about getting older and needing help to stay at home or in institutions like nursing homes or assisted-living facilities.

Many suggested changes to U.S. policy, like expanding the government’s payments for care and allowing more immigrants to stay in the country to help meet the demand for workers. Some even said they would rather end their lives than become a financial burden to their children.

Many readers blamed the predominantly for-profit nature of American medicine and the long-term care industry for depleting the financial resources of older people, leaving the federal-state Medicaid programs to take care of them once they were destitute.

“It is incorrect to say the money isn’t there to pay for elder care,” Jim Castrone, 72, a retired financial controller from Placitas, N.M., commented. “It’s there, in the form of profits that accrue to the owners of these facilities.”

“It is a system of wealth transference from the middle class and the poor to the owners of for-profit medical care, including hospitals and the long-term care facilities outlined in this article, underwritten by the government,” he added.

But other readers pointed to insurance policies that, despite limitations, had helped them pay for services. And some relayed their concerns that Americans were not saving enough and were unprepared to take care of themselves as they aged.

“It was a long, lonely job, a sad job, an uphill climb.”

Marsha Moyer

What other nations provide

Other countries’ treatment of their older citizens was repeatedly mentioned. Readers contrasted the care they observed older people receiving in foreign countries with the treatment in the United States, which spends less on long-term care as a portion of its gross domestic product than do most wealthy nations.

Marsha Moyer, 75, a retired teaching assistant from Memphis, said she spent 12 years as a caregiver for her parents in San Diego County and another six for her husband. While they had advantages many don’t, Ms. Moyer said, “it was a long, lonely job, a sad job, an uphill climb.”

In contrast, her sister-in-law’s mother lived to 103 in a “fully funded, lovely elder care home” in Denmark during her last five years. “My sister-in-law didn’t have to choose between her own life, her career and helping her healthy but very old mother,” Ms. Moyer said. “She could have both. I had to choose.”

Birgit Rosenberg, 58, a software developer from Southampton, Pa., said her mother had end-stage dementia and had been in a nursing home in Germany for more than two years. “The cost for her absolutely excellent care in a cheerful, clean facility is her pittance of Social Security, about $180 a month,” she said. “A friend recently had to put her mother into a nursing home here in the U.S. Twice, when visiting, she has found her mother on the floor in her room, where she had been for who knows how long.”

Brad and Carol Burns moved from Fort Worth, Texas, in 2019 to Chapala, Jalisco, in Mexico, dumping their $650 a month long-term care policy because care is so much more affordable south of the border. Mr. Burns, 63, a retired pharmaceutical researcher, said his mother lived just a few miles away in a memory care facility that costs $2,050 a month, which she can afford with her Social Security payments and an annuity. She is receiving “amazing” care, he said.

“As a reminder, most people in Mexico cannot afford the care we find affordable and that makes me sad,” he said. “But their care for us is amazing, all health care, here, actually. At her home, my mom, they address her as Mom or Barbarita, little Barbara.”

Insurance policies debated

Many, many readers said they could relate to problems with long-term care insurance policies, and their soaring costs. Some who hold such policies said they provided comfort for a possible worst-case scenario while others castigated insurers for making it difficult to access benefits.

“They really make you work for the money, and you’d better have someone available who can call them and work on the endless and ever-changing paperwork,” said Janet Blanding, 62, a technical writer from Fancy Gap, Va.

Derek Sippel, 47, a registered nurse from Naples, Fla., cited the $11,000 monthly cost of his mother’s nursing home care for dementia as the reason he bought a policy. He said he pays about $195 a month with a lifetime benefit of $350,000. “I may never need to use the benefit(s), but it makes me feel better knowing that I have it if I need it,” he wrote. He said he could not make that kind of money by investing on his own.

“It’s the risk you take with any kind of insurance,” he said. “I don’t want to be a burden on anyone.”

Pleas for more immigrant workers

One solution that readers proposed was to increase the number of immigrants allowed into the country to help address the chronic shortage of long-term care workers. Larry Cretan, 73, a retired bank executive from Woodside, Calif., said that over time, his parents had six caretakers who were immigrants. “There is no magic bullet,” he said, “but one obvious step — hello people — we need more immigrants! Who do you think does most of this work?”

Victoria Raab, 67, a retired copy editor from New York, said that many older Americans must use paid help because their grown children live far away. Her parents and some of their peers rely on immigrants from the Philippines and Eritrea, she said, “working loosely within the margins of labor regulations.”

“These exemplary populations should be able to fill caretaker roles transparently in exchange for citizenship because they are an obvious and invaluable asset to a difficult profession that lacks American workers of their skill and positive cultural attitudes toward the elderly,” Ms. Raab said.

“For too many, the answer is, ‘How can we hide assets and make the government pay?’”

Mark Dennen

Federal fixes sought

Others called for the federal government to create a comprehensive national long-term care system, as some other countries have. In the United States, federal and state programs that finance long-term care are mainly available only to the very poor. For middle-class families, sustained subsidies for home care, for example, are fairly nonexistent.

“I am a geriatric nurse practitioner in New York and have seen this story time and time again,” Sarah Romanelli, 31, said. “My patients are shocked when we review the options and its costs. Medicaid can’t be the only option to pay for long-term care. Congress needs to act to establish a better system for middle-class Americans to finance long-term care,” she said.

John Reeder, 76, a retired federal economist from Arlington, Va., called for a federal single-payer system “from birth to senior care in which we all pay and profit-making removed.”

Mark Dennen, 69, from West Harwich, Mass., said people should save more rather than expect taxpayers to bail them out. “For too many, the answer is, ‘How can we hide assets and make the government pay?’ That is just another way of saying, ‘How can I make somebody else pay my bills?’” he said, adding: “We don’t need the latest phone/car/clothes, but we will need long-term care. Choices.”

<h2″>Questioning life-prolonging procedures

A number of readers condemned the country’s medical culture for pushing expensive surgeries and other procedures that do little to improve the quality of people’s few remaining years.

Dr. Thomas Thuene, 60, a consultant in Roslindale, Mass., described how a friend’s mother who had heart failure was repeatedly sent from the elder care facility where she lived to the hospital and back, via ambulance. “There was no arguing with the care facility,” he said. “However, the moment all her money was gone, the facility gently nudged my friend to think of end-of-life care for his mother. It seems the financial ruin is baked into the system.”

Joan Chambers, 69, an architectural draftsperson from Southold, N.Y., said that during a hospitalization on a cardiac unit she observed many fellow patients “bedridden with empty eyes,” awaiting implants of stents and pacemakers.

“I don’t want to be a burden on anyone.”

Derek Sippel

“I realized then and there that we are not patients, we are commodities,” she said. “Most of us will die from heart failure. It will take courage for a family member to refuse a ‘simple’ procedure that will keep a loved one’s heart beating for a few more years but we have to stop this cruelty.

“We have to remember that even though we are grateful to our health care professionals, they are not our friends, they are our employees and we can say no.”

One physician, Dr. James D. Sullivan, 64, from Cataumet, Mass., said he planned to refuse hospitalization and other extraordinary measures if he suffered from dementia. “We spend billions of dollars, and a lot of heartache, treating demented people for pneumonia, urinary tract infections, cancers, things that are going to kill them sooner or later, for no meaningful benefit,” Dr. Sullivan said. “I would not want my son to spend his good years, and money, helping to maintain me alive if I don’t even know what’s going on,” he said.

Thoughts on assisted dying

Others went further, declaring they would rather arrange for their own deaths rather than suffer in greatly diminished capacity. “My long-term care plan is simple,” said Karen D. Clodfelter, 65, a library assistant from St. Louis. “When the money runs out I will take myself out of the picture.” Ms. Clodfelter said she helped care for her mother until her death at 101. “I’ve seen extreme old age,” she said, “and I’m not interested in going there.”

Some suggested that assisted dying should be a more widely available option in a country that takes such poor care of its elderly. Meridee Wendell, 76, from Sunnyvale, Calif., said: “If we can’t manage to provide assisted living to our fellow Americans, could we at least offer assisted dying? At least some of us would see it as a desirable solution.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The retired pilot went to the hospital.

— Then his life went into a tailspin.

Many older people are one medical emergency away from a court-appointed guardian taking control of their lives

By Mary Jordan

When Douglas Hulse pulled his Ford Mustang convertible into a Florida gas station three years ago, he looked so distressed that someone called 911.

An ambulance rushed him to Orlando Health South Seminole Hospital, where doctors said he had a stroke. At 80, the retired pilot who had flown famous passengers around the country could no longer care for himself.

But Hulse lived alone — as 3 out of 5 Americans in their 80s do.

A hospital can be liable if a patient is discharged into an unsafe environment. Because Hulse lived alone and the hospital officials saw no sign that he had family, that put them in a bind when his health didn’t improve. So they argued in court that he was no longer capable of making his own decisions and needed a guardian — a caretaker with enormous legal power.

When a judge agreed, Hulse lost basic freedoms: He couldn’t spend his own money or decide where to live. The lifelong Republican who had just cast his ballot in the 2020 presidential primary even lost his right to vote. He was quickly moved to a nursing home. His new guardian, a woman he had never met, began selling his house and his belongings.

Hulse had joined 1 million Americans in a guardianship, a court-sanctioned arrangement created to protect vulnerable people — some young, but many elderly. The system has been widely criticized for inviting abuse and theft. Local judges give extraordinary power to a guardian, including access to the bank account of the person in their care, despite a lack of effective ways to monitor them. When excessive billing, missing money and other abuses are discovered, guardians are rarely punished. Prosecutors are keenly aware they were appointed by a judge.

As America ages, there is new focus on this legal arrangement, especially in Florida, a mecca for seniors where state officials have called the rising number of elderly the “silver tsunami.” Already, Florida has 2 million residents 75 or older — more than the entire population of 14 other states. Many moved here from other parts of the country, far from family, and are showing up alone in emergency rooms.

What happened to Hulse over the past three years shines a light on the serious flaws in this government system and on the hospital pipeline that thrust Hulse into it. During the coronavirus pandemic, more hospitals went to court to seek guardianships; it was a way to legally move out patients and free up beds. Today, the practice quietly continues as an efficient way to discharge elderly patients who cost hospitals money the longer they stay.

“This should scare people to death,” said Rick Black, the founder of the Center for Estate Administration Reform who has examined thousands of guardianship cases and has seen a rise in hospitals initiating them. “This is a common practice nationwide, and its adoption is growing.”

In court, the Orlando hospital requested that Hulse be assigned Dina Carlson, a 51-year-old former real estate agent who became a professional guardian. After a judge assigned her, Hulse was immediately moved out of the hospital and into a nursing home. Carlson’s sale of his home raised suspicions because of its seemingly low price in a hot market, and an inspector general’s investigation later found “probable cause” of exploitation of an elderly person and a scheme to defraud.

Carlson denied any wrongdoing, and no criminal investigation was ever opened. “I am a little bit salty about this whole thing,” Carlson said in an interview. She said she wanted “to be a ray of sunshine” for elderly people.

Guardianships are not well understood. Rules vary by jurisdiction, and key information is often sealed by judges.

“People don’t realize how abusive the system is,” said Pinellas County Circuit Court Clerk Ken Burke, who led a recent Florida task force to improve guardianships. “If they knew, there would be bigger cries for reform.”

Very often, the person in a guardianship is unable to publicly complain and has nobody in their life to do it for them.

But it turned out Hulse did have family, and they were searching for him.

Douglas Hulse was born in 1939 and raised in McLean, Va., where his father was a lobbyist for the trucking industry. In the 1950s, Hulse enrolled in a Florida college and became a pilot.

Like his father, Hulse was a Republican who loved to talk politics. He also drew caricatures of every president in the last half century. After flying Henry Kissinger and Alexander Haig, former Republican secretaries of state, he proudly showed off photos he took of them to his sister, niece and nephew.

He never married or had children. He kept busy, teaching flying and taekwondo. But when he retired he spent more time alone. Five residents on his street in Lake Mary, near Orlando, said they barely knew the tall, blue-eyed neighbor. He had lived there 25 years, longer than many in a transient place.

Raymond Charest, president of the Seminole County Gun and Archery Association, said that in the 1990s Hulse taught members about how to safely handle and store guns but that recently he wasn’t involved in the club. “I would see him shooting out there. But it was just, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’ and that was it.”

Katie Thompson, Hulse’s niece, said for years her uncle regularly visited her mother, father, brother and her in the Philadelphia area. She also went to see him at his three-bedroom Florida home full of exceptional items he collected in his travels, including a Las Vegas-style slot machine.

But his visits stopped when his sister, Katie’s mother, developed dementia before she died in 2018. Hulse had seen his own mother die the same way. “I think it just got too hard for him,” his niece said.

After Hulse’s only sibling passed away, he became harder to reach, but he eventually responded to calls and emails.

After his stroke, Hulse was confused and apparently unable to tell anyone to call his family. It’s unclear what efforts the hospital made to track down any relatives.

Geo Morales, a spokesman for the Orlando Health South Seminole Hospital, said he could not discuss details of Hulse’s case because of privacy laws. He emailed a statement that said the hospital works “with various community partners in an attempt to reach next of kin. However, reaching a patient’s next of kin is not always possible.”

“We are seeing more of these patients with dementia and other ailments who live alone and/or are estranged from relatives,” Morales said in an email. He strongly urged people to draw up a will or designate someone to make their health decisions and to note this in their medical file.

Hulse had not. In these cases, court records show, hospitals often turn to guardianships, even though they are widely considered a last resort and difficult to reverse.

For generations, judges have been assigning a relative or close friend as the protector of someone unable to make their own decisions. But more people are socially isolated and have no one they can count on at the end of their life. Even many people with close relatives are estranged from them.

In many societies, family members of different generations live under one roof. But one of the most dramatic shifts in the American lifestyle is single-person households. Many live alone beginning in their 20s and by the time they are in their 80s, most live by themselves.

So judges now often assign professional guardians, a person paid to care for someone they don’t know. Carlson told the court she was already caring for 18 others when she was assigned to Hulse. Carlson charged him $65 an hour, according to her bills filed in court. When a judge signed off, she paid herself from Hulse’s bank account.

In some states, the only requirement to be a guardian is to be 18 years old. Florida has more requirements including a background and credit check. But still, compare the 40-hour training course with, for instance, the 900 educational hours required to become a licensed barber.

Yet these caretakers control people’s lives and money. In just one Florida county, Palm Beach, guardians control about $1 billion, according to Anthony Palmieri, deputy inspector general for the Palm Beach Circuit Court.

“You have your nail techs and tennis pros — their business is not so good and they want something more lucrative and they’re jumping into guardianship,” Palmieri said.

But adding an independent monitor from outside the court, a frequent recommendation, is expensive. “The system would be cured, in my opinion, by the Department of Elder Affairs taking responsibility for guardianship” said Burke, the Pinellas court clerk.

In Florida, even funding a statewide guardianship database was a battle. Currently, there isn’t an official number of how many people are in them; best estimates are about 50,000. Each county keeps its own records, and some do that better than others. When the database goes online, it will give the first statistical snapshot of the system.

Critics have called for a uniform system with more oversight. But several Florida officials said those who benefit from the current, complex system, including lawyers, impede reform. Efforts to make attorneys’ fees in these cases more publicly visible have also failed.

“There are a lot of great attorneys out there,” Burke said. But the court clerk said there has been pushback from the Real Property, Probate and Trust Law Section of the Florida Bar, adding, “It’s a trade union for all practical purposes, and it protects their members and the fees they receive.”

These attorneys are influential in the state legislature, where their expertise is often sought to draft laws related to guardianships and estates.

John Moran, chair-elect of the Florida Bar’s Real Property, Probate and Trust Section, said far from blocking improvements, it has stated policy positions that seek reforms, including more transparency. Asked why legal fees cannot be more readily known, Moran cited privacy concerns of the incapacitated person. He also emphasized that “no lawyer gets paid without a judge’s approval.”

So the system with few guardrails continues. Court clerks audit guardians’ reports that detail how they spend the money of the person in their care, among other things. Any irregularities are to be flagged to a judge. But clerks are swamped, with little time to read through a case file that is often thousands of pages.

Grant Maloy, the Seminole County court clerk, said his office has a far bigger caseload today than 15 years ago yet a smaller budget.

The judges are overloaded, too. Pinellas County has two judges and two magistrates overseeing 3,000 guardianships — in addition to other types of cases.

No witness or body camera accompanies a guardian into a person’s home. They are trusted to accurately inventory all valuables in their court report. “There could be $5,000 stuffed under the sofa, and if the guardian pocketed it, who would know?” said Burke, the Pinellas court clerk.

The task force organized by the state clerks and comptrollers last year said hospitals should find a less drastic way to deal with patients costing them money, such as authorizing someone to be their power of attorney or health surrogate. It also sought a ban on requesting a specific guardian because that raises concerns about the guardian’s allegiance — is it to the patient or the hospital giving them work?

A Washington Post review of guardianship records in central Florida found scores of recent petitions by hospitals seeking a guardian for patients 65 and older, and many asked for a specific professional guardian.

In April 2020, when Hulse was ready to be discharged, a staff member of the Orlando hospital signed a petition to the court stating that he had “no one to take care of the financial and medical decisions.”

Hulse, like most patients over 65, was covered by Medicare. It pays the hospital by diagnosis, not length of stay, an attempt to stop excessive billing. Generally it pays a hospital $23,000 for an elderly stroke patient in Orlando, a sum that assumes a five-day stay. After that, a hospital starts losing money. A new patient in the same bed would bring in thousands of dollars a day.

The American Hospital Association said more patients are staying “excessive days” and has lobbied for increased Medicare payments. Many hospitals are also overwhelmed by people who are homeless or have a mental illness and other patients unable to pay their bills. An AHA spokesman also said a hospital may initiate a guardianship but a judge approves it.

Laura Sterling, an attorney hired by the Orlando hospital, recommended Carlson as Hulse’s guardian. In Florida, lawyers represent guardians in court, and Sterling was Carlson’s lawyer. In her court filing that requested Carlson, Sterling does not mention that if Carlson was assigned, she also would be paid as her lawyer, at a rate of $300 an hour.

Sterling did not respond to requests for comment. There is no Florida rule prohibiting a lawyer from representing both the hospital and the guardian the hospital recommended in the same case.

Moran, from the Florida Bar, said he could not speak for the lawyers’ group but said that scenario raised “all kinds of red flags.”

Sterling’s role in Hulse’s case was largely to file court motions. One sought approval for a monthly transfer of $10,000 from Hulse’s brokerage account to his checking account so Carlson could pay his nursing home and other bills. Another asked the court for $2,925 for Carlson, for time spent opening Hulse’s mail, arranging physical therapy and other tasks during her first four months. The money to pay Sterling and Carlson came from Hulse’s accounts, which had more than $1.5 million, according to a note in his file.

In August 2020, after Hulse had fallen five times at the Lake Mary nursing home, Carlson moved him to a smaller facility. She also started liquidating his possessions, reporting to the court that she sold his cars, paintings, a diamond ring, camera equipment and guns. Many items were sold in cash at an estate sale, according to neighbors who went to it. It’s unclear how much Carlson reported earning for Hulse; most financial details are kept sealed.

In April 2021, Carlson signed an agreement to sell Hulse’s house with Kimberly and Mark Adams, husband-and-wife real estate agents who lived in her gated community lined with palm trees, giving them a 6 percent commission, an amount typically split between the seller’s and buyer’s agents. Carlson quickly sold the home for $215,000 before it was even publicly known to be on the market, according to the inspector general’s investigation. A company called Harding Street Homes bought Hulse’s home and resold it a few months later for $347,000 — $132,000 more than Hulse got for it. Efforts to reach the person who runs that company were unsuccessful.

Soon after the home was sold, Katie Thompson, Hulse’s niece, expanded her search for her uncle. Busy with her job and her first baby, she had not realized for months that her brother and father also had not heard from Hulse. She was a legal researcher who used Westlaw, an online legal database, and when she typed her uncle’s name into it, she was stunned to see him listed in a guardianship case.

“How could the hospital do this?” she thought. Since older people end up in an emergency room, she figured there must be a system for contacting family. “If they just called me none of this would have happened.”

In the days after Carlson became Hulse’s guardian, she did not call his relatives, either. Carlson said it was unfortunate but no one’s fault: “How does a person find out about somebody who doesn’t live in the same state? About family who don’t have the same last name? I didn’t have anybody’s name to Google.”

Thompson has her own regrets. For one thing, she wished she had gotten on a plane earlier despite worries about the pandemic.

On top of everything else, she said, she and her brother were helping their father, heartbroken over the death of their mother. “I kept thinking if something was really wrong with my uncle I would have gotten a call,” she said.

Thompson and her brother began calling those involved in the court case. But nobody answered their key question: Where was Hulse?

Finally, a court clerk advised them to write a letter to the court.

“We want to know where our uncle is, that he is safe and well cared for, and that his money was being well-stewarded so that he can remain so,” Katie Thompson wrote on July 28, 2021, to Seminole County Circuit Court Judge Donna Goerner. “We want to be able to be in contact with him.”

Months passed with no reply.

Around the start of 2022, Hillary Hogue was sitting at her kitchen table in Naples, Fla., scrolling online through guardianship cases, when she randomly clicked on Hulse’s.

“I look for red flags and when you see a hospital is involved, it’s a red flag,” said Hogue. A single mom of two teenage boys, she became an unpaid citizen watchdog after her own horrible guardianship experience. To get her father released from one, she paid over $100,000 in legal fees. He now lives with her.

Hogue knew other cases where hospitals did not notify relatives before setting in motion a hard-to-stop legal process. “It’s just outrageous. Doesn’t anyone care about Mr. Hulse?”

She zeroed in on the price of Hulse’s home, which seemed remarkably low to her, especially after she looked up more information about it. Aware of other cases where guardians sold homes at bargain rates to friends or for kickbacks, Hogue filed a complaint with the office that regulates guardians, knowing it would draw scrutiny to Hulse’s case.

Katie Thompson, meanwhile, inquired about getting her uncle released from his guardianship. The Florida lawyer she contacted told her that she could spend $20,000 trying, with no guarantee of success. Hulse’s health was worsening and soon, any hope she had of moving him to Pennsylvania so she could manage his care became less of an option.

In January 2022, Carlson finally contacted the family. She called Jonathan Thompson, Hulse’s nephew, who believes her call was prompted by the family’s letter to the judge six months earlier. “I guess the letter finally got to the top of someone’s pile,” he said.

Carlson outlined Hulse’s medical problems and said he probably had a series of strokes. Because of the pandemic, she said, for a long stretch at the start of the guardianship she had not met him in person. She offered to arrange FaceTime calls. and soon Katie and Jonathan were talking to Hulse about old family trips to Gettysburg, Pa., and Cape Canaveral, Fla.

But they were wary. A state investigator, spurred by Hogue’s complaint, had called them, asking questions about Carlson.

They had their own questions: Since Carlson knew Hulse had the money for in-home aides why was he in a strange place that added to his confusion? Didn’t she see their cards mailed to his home or their contacts in his phone? And, why would a former real estate agent undersell a home without advertising it?

In July 2022, the inspector general’s office issued a critical report, a copy of which was obtained by The Post through a Freedom of Information Act request.

It stated that Carlson, when seeking court approval for the sale of Hulse’s home, submitted a “deficient, deceptive, and fraudulent” comparative market analysis supplied by Kimberly Adams, the real estate agent. Hulse’s home was “undervalued” and not publicly advertised.

The inspector general’s investigation also found no permits required for significant renovation. It concluded that after “superficial changes,” Hulse’s home was “flipped” for a big profit for the buyer — money that Hulse lost out on.

The inspector general’s office, lacking the investigative power of law enforcement, including the ability to subpoena bank records, pushed for a criminal investigation. It urged law enforcement to look into the handling of Hulse home and two others Carlson sold with the same real estate agents, stressing it had found “probable cause” that Carlson and the real estate agents “engaged in a scheme to defraud.”

Reached by phone, Kimberly Adams denied knowing anything about the inspector general investigation: “I honestly don’t know what you are referring to … I sell property all the time.”

Mark Adams did not return phone calls.

Carlson defended her sale of Hulse’s home. She told a state investigator that it was in “very poor condition,” according to the inspector general report, and that “it wasn’t safe to allow the general public” inside because there were “a lot of valuables in the house, a lot of guns and a lot of ammo as well.”

But Hulse’s family said he kept his guns in a safe, and Carlson billed Hulse for finding locksmiths to open his gun safe.

In The Post interview, Carlson said there are ways to improve the guardianship system but most importantly family should take care of their relatives. Then she quickly added, “In Doug’s case, no one knew about his family.”

Carlson did not answer questions about whether she saw the names and addresses of Hulse’s niece and nephew on cards and gifts mailed to his home. She also distanced herself from hospitals: “I have never met anyone at the hospital. Lawyers do.”

Carlson said she got Hulse’s case when “a lawyer” sent an email to her and other professional guardians, asking if anyone had “the bandwidth” to care for another patient leaving a hospital.

In February, Katie Thompson did not meet Carlson when she flew to Orlando with her 3-month-old, her second child, to visit her uncle. He seemed comforted by the photos she brought of his childhood home in Virginia, of her mother and him when they were young. “He was very sick then. I was grateful for the time with him.”

On March 16, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement said its preliminary inquiry found “no evidence” to warrant a criminal investigation “at this time,” according to an email received in the FOIA request.

Advocates for the elderly say police and prosecutors often do not treat financial exploitation of elderly people seriously enough and are reluctant to sink time into cases where the only witness has dementia, if still alive.

Two days after the state declined to pursue a criminal investigation, Hulse died.

Carlson had prepaid for the same basic cremation package she purchases for many in her care. Hulse’s family had his ashes buried with his parents on Long Island.

Katie Thompson received a small box from Carlson with photos and a few other items that belonged to her uncle. She and her brother are now waiting to learn what is left in his estate.

The Florida Department of Elder Affairs, after being contacted by The Post, reprimanded Carlson for her failure to file timely reports. Her penalty: She must take eight more hours of classroom training.

“Not even a slap on the wrist,” said Hogue. “The result is the corruption continues, and it only gets worse, bigger and bigger.”

Said Katie Thompson, “This system trusts a person to be a guardian angel, but people are not.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

6 Uncomfortable But Necessary Questions To Ask Your Older Parents

— It may never feel like the “right” time to have these conversations, but experts say you shouldn’t hold off.

Talking to your parents about their end-of-life wishes may feel like an uncomfortable or morbid topic to bring up, and one that’s tempting to avoid altogether. But you don’t want to wait until your parents are in the midst of a health crisis to have these discussions when stress levels are high and they may have trouble communicating their wishes.

According to The National Hospice Foundation, talking about end-of-life wishes preemptively “greatly reduces the stress of making decisions about end-of-life care under duress. By preparing in advance, you can avoid some of the uncertainty and anxiety associated with not knowing what your loved ones want. Instead, you can make an educated decision that includes the advice and input of loved ones.”

We asked end-of-life experts to share some of the uncomfortable but important questions to ask your parents. Below, they also offer advice on how to approach these daunting conversations.

1. Do you have an up-to-date advance care directive?

Advanced directives include legal documents such as a living will and medical power of attorney. A living will explains what health care treatment a person would — and would not — like to receive near the end of life, or if they are otherwise unable to speak for themselves. A medical power of attorney — sometimes referred to as a durable power of attorney for health care — is a document naming the person who will be responsible for making medical decisions if the patient cannot. It’s important that your parents not only put these preferences in writing, but also talk through them with you so you can properly honor their wishes.

Only one-third of Americans have advanced care directives in place, “leaving family members often struggling to determine what their parent’s wishes are or making choices that they may not have made for themselves,” Loren Talbot, director of communications for the International End-Of-Life Doula Association (INELDA), told HuffPost. “There are resources that are culturally competent and multi-language guides to help walk your folks through the process. Make sure you review by the state you live in.”

To get started, Talbot recommended resources such as The Conversation Project, Five Wishes and My Directives.

Dr. VJ Periyakoil is a palliative care doctor, as well as the founder and director of the Stanford Letter Project, a tool that helps people plan for their future including end-of-life medical care, using different letter templates.

For example, their “What Matters Most” template “helps a person write a letter to their doctor and health care team about their goals of care and their values,” Periyakoil told HuffPost. “Family members can use our letter template to have a gentle conversation with their parents and help them complete their letter advance directive to their doctor.”

It includes prompts about how medical decisions are made in the family, how bad news is handled, whether they’d want to be put on a ventilator (breathing machine) or sedated if they were in extreme pain.

“The goal of this conversation is to ensure that our parents have a voice in their care and give them ample opportunity to provide us with anticipatory guidance,” Periyakoil told HuffPost.

2. Have you thought about what you want the end of your life to look like? If so, can you share what you’re envisioning?

Some folks have a clear picture of what they want theirs to look like; others may avoid such thoughts, Talbot said. This question will help you understand their desires so you know how to best support them when this time comes.

“Just let them talk at that moment and listen. Some possible follow-up could be: Do you know where you want to be — home or care facility? What would the room look like? Does it have pictures of their loved ones pinned up or specific music playing as they are actively dying?” she said.

“Some of the same choices we make during life, we can plan for at death. Do you want to have any rituals or customs take place prior to death? There are so many questions that can be shared to help people really define their needs. End-of-life doulas are trained in asking these questions, and can support individuals and their families to create a plan.”

“The time to broach the conversation is now. It doesn’t serve you or your loved one if you continue to avoid it or ignore the reality of death.”

– Aditi Sethi, hospice physician and end-of-life doula

To help guide these conversations, Talbot recommended resources such as The Death Deck, Death Over Dinner, GoWish Cards, or connecting with an end-of-life doula via the INELDA Directory.

You might also ask about how flexible your parent is about potential living arrangements in the event that their caregiving needs increase, said hospice physician and end-of-life doula Aditi Sethi.

For example: “Would you move into our home with our three kids so we could take care of you? Or could we move in with you?” Sethi, who is also the executive director of Center for Conscious Living and Dying, told HuffPost.

“There is fear amongst some parents that their children are too busy to care for them or incapable for various reasons. With our caregiver crisis, aging population, undesirable options for care — few people want to go to nursing homes and few can afford 24/7 care in the home — it is imperative that we all get creative and let go of being rigid to how it ought to be.”

3. What do you expect of me and your other kids as you approach your dying season?

This conversation might include asking your parents about how involved they’d like you to be with things like personal care — bathing them or repositioning them in bed, for example.

“Being clear with your loved ones about their wishes for their care, assumptions and expectations of your involvement, can alleviate the stress of having to decide at the last minute or do something that will cause more agitation, resentment and hard feelings,” Sethi said.

“This is especially true for cultural norms and expectations in a modern world where children are not always local and there may be some unspoken assumptions and expectations of them that may not be met due to obligations, commitments,” she added.

4. What do you want us to do with your belongings after you’re gone?

Dealing with a deceased loved one’s possessions “can be a daunting task if not addressed or discussed prior to a death” — and one that can stir up a lot of conflict among living family members, said Sethi. So it’s best to talk this through with your parents ahead of time.

“There is much involved in distributing, selling, discarding or dispersing of belongings, cherished objects, furniture, cars, house, etc.,” she said. “It’s helpful for your loved ones still alive if you organize paperwork, designate your wishes for where personal objects are going — this avoids disagreements, drama and ambiguity — and get your affairs in order as much as possible before you go.”

5. What would you like to happen to your body after you die?

While it’s important to talk about their preferences for how their belongings are handled, it’s also important to discuss what will happen to their physical body.

“Do they know what their options are after they die? Have they considered a brain donation, what type of service they want, a home funeral, a green burial, a traditional funeral or cremation?” Talbot said. “There are so many more options today then they may even know. Knowing and asking what they may want after death is honoring their autonomy during their life.”

6. If you die before your spouse, what resources are available to help mom/dad as they age?

These resources might include long-term care insurance or money set aside for the care of an aging parent, Sethi said.

“Some parents have already bought into a retirement community. It’s important to know these things to best care for your living parent,” she said.

Advice On How To Broach These Conversations

End-of-life professionals share guidance on how to approach these difficult conversations with your parents.

First, know that it may never feel like the “right” time to talk about your parents’ end-of-life wishes. Don’t put off these conversations or wait for the perfect moment to strike because then they may never happen.

“The time to broach the conversation is now,” Sethi said. “It doesn’t serve you or your loved one if you continue to avoid it or ignore the reality of death.”

If you try to talk about end-of-life wishes when your parents are healthy, it’s possible they’ll think it’s “too premature,” she said.

“If you do it over the holiday dinner table when all the family is together, it’s ‘too serious,’ ‘too morbid’ or ‘not the proper time,’” Sethi said.

But if you hold off on talking about this until they’re diagnosed with a terminal illness, your family may still want to avoid having these discussions because it seems pessimistic, and they’d rather stay hopeful that things will turn around.

“And then, as someone is clearly dying, family may not want to broach the conversation for fear it may cause anxiety or depression — and oftentimes family and friends don’t now how to broach this conversation,” Sethi said.

She suggests revisiting end-of-life discussions roughly every three to five years or when there’s a major life event such as a divorce, serious diagnosis or decline in their health.

To open up the discussion, Periyakoil said you can try this pitch, which she has tested and said “works really well.”

“I am getting old, and you both are getting older. This is a wonderful thing for our family, and I hope we have many wonderful years together. As we prepare for the future, I would like us to think about completing some simple forms that will help our doctors and our family best support us,” she told HuffPost.

“If you get push back like, ‘Not now!’ or ‘It’s too early,’ you should gently respond, ‘It is always too early until it is too late.’”

No adult is ever too young or too old to start discussing these decisions, Periyakoil said. In fact, when you’re having these conversations with your parents, you can also start to contemplate your own preferences if you haven’t already.

Another way into the conversation is by leaning into what your family is interested in, Talbot said.

“If they love movies, there are so many great end-of-life films out there. If they or you love hosting dinner parties, consider a ‘Death Over Dinner’ night. Having conversations about planning for end-of-life and death can be healing and help to alleviate family conflict and unrecognized wishes.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Aging for Two

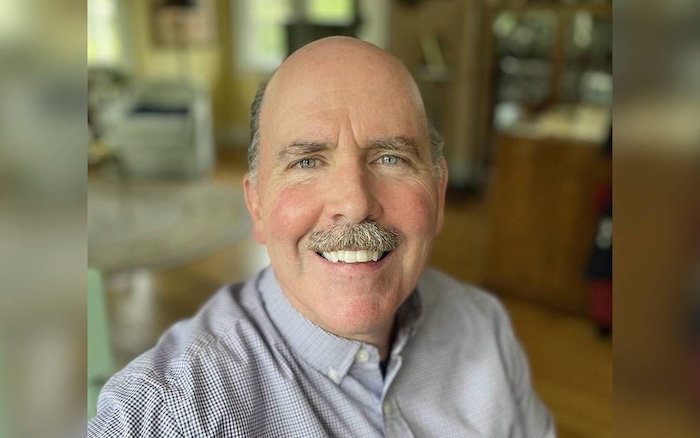

— How a longtime husband copes with his changing appearance. Humor helps.

“Are you the father of the deceased?”

This jarring question came from a woman I did not know at a relative’s memorial service a couple years ago. The reason it was jarring? The deceased had died at age 59, and at that time I was 52. Plus, I was with my two daughters, ages 18 and 21, who couldn’t resist a chuckle as I pointed to the 86-year-old father of the deceased and said: “No, that’s him over there.”

That was the first (and so far, the only) time I have been mistaken for an 86-year-old. But it was the latest incident in my complicated, triangular relationship with my chronological age (how old I am), my “subjective” age (how old I feel) and what I call my “apparent” age (how old I look).

I have always looked older than my age, which was a benefit back in high school when I grew a mustache and beard by tenth grade.

I have always looked older than my age, which was a benefit back in high school when I grew a mustache and beard by tenth grade. As a teenage boy, looking older creates mystique and prompts awe-stricken fellow students to ask if you can buy them beer.

The flip side, however, was my early signs of balding. As a baseball teammate exclaimed one day, “Dude, you’re going to have a widow’s peak!” I didn’t know what that meant, but it did not sound good.

By the end of high school (and the beginning of my hairline’s retreat), I decided to embrace my “inner balding man” and go for laughs, in part because he’s always visible on the outside anyway. My first performance of this approach occurred in my early 20s during my toast at my older brother Mark’s wedding.

After informing the crowd that I was Mark’s older brother, I mentioned that I used to be his younger brother. Then I recounted our recent trip to a bar where my four-years-older-than-me brother had to show his I.D. while I did not, which “proved” that my age had bypassed his age.

My 20s also featured meeting and eventually marrying my beautiful wife, Michele, who is two years younger than me and has always had a “baby face.” We have been together for 34 years, and thanks to genetics, rigorous self-care and regular moisturizing, she still looks much younger than her age (more on that soon).

The Hits Kept Coming

When I was 28 and took her to my 10-year high school reunion, I was embarrassed for her to hear a former classmate who was gobsmacked by my hairline state: “Vince, you look so … old.” All I could think to say was “thanks, it’s nice to see you too!”

“My dad doesn’t need many haircuts because he only has half-hair!”

In my 30s, the hits kept coming. Michele and I now had two young daughters, and one day the five-year-old boy who lived next door was playing with our older daughter, Lauren. When the kids were on our backyard swings, the boy pointed at me and said: “Hey, maybe your grandpa can push us!” For a moment, I thought my father or father-in-law had shown up behind me.

This embarrassing incident was followed by six-year-old Lauren making me squirm at a salon. During one of her chatty haircuts, she was telling the stylist about the hairdos of her mother and sister. Then she pointed at me and announced to a crowd: “My dad doesn’t need many haircuts because he only has half-hair!”

In my early 40s, as I continued to age and Michele continued to moisturize, the inevitable happened: my wife was mistaken for one of my children. At a science center, our family of what I saw as obviously two adults and two children approached the ticket window. The woman glanced at us and said to me: “One adult and three kids?” Michele shot me a sympathetic smile but also got a laugh out of that one.

Our Aging Discrepancies

Laughter, indeed, has been a way for Michele and me to bond over our aging discrepancies. At one of our recent wedding anniversary dinners, I gave Michele a bonus present right before dinner. The gift? Admitting that after I dropped her off, parked the car, and entered the restaurant, the host said to me: “Let me show you to your daughter’s table.”

Better coping mechanisms have been humor and an appreciation of my health, which continues to be good thanks in part to regular exercise.

Now in my 50s, I have learned to accept the things I cannot change about my appearance. There were times when I considered Rogaine or a hairpiece, but those didn’t feel right for me. Better coping mechanisms have been humor and an appreciation of my health, which continues to be good thanks in part to regular exercise.

Another coping strategy has been to reframe my aging conundrum into sunnier terms. Rather than lament that I’m in my 50s but appear to be in my 80s, I take pride in how spry I must look to strangers whenever I do yardwork, lift something heavy, or just move quickly. I imagine their low expectations leading to thoughts like “that 80-year-old moves like a 50-year-old!”

People sometimes describe pregnant women as “eating for two,” though my baby-faced wife never liked that phrase during her pregnancies years ago. But it seems that during our long relationship I have been taking the burden of aging off her plate, so to speak, by “aging for two.”

Granted, there are far more cultural pressures placed on women than on men when it comes to aging gracefully. And the unfair social penalties for women in their 50s who may look older than their chronological age are nothing to laugh about.

Still, my wife and I continue to enjoy the absurdities of (mostly my) aging. At a recent wake, a relative who had not seen me in many years actually asked Michele out of my earshot: “Where is your husband?” When Michele pointed at me, the woman asked as if seeing a ghost: “That’s Vince?!” Clearly, I had become unrecognizable — you might even say “deceased” — to the woman.

At least I wasn’t mistaken for the ghost’s father.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!