By JESSICA NUTIK ZITTER

[I] WAS leafing through a patient’s chart last year when a colleague tapped me on the shoulder. “I have a patient who is asking about the End of Life Option Act,” he said in a low voice. “Can we even do that here?”

I practice both critical and palliative care medicine at a public hospital in Oakland. In June 2016, our state became the fourth in the nation to allow medical aid in dying for patients suffering from terminal illness. Oregon was the pioneer 20 years ago. Washington and Vermont followed suit more recently. (Colorado voters passed a similar law in November.) Now, five months after the law took effect here in California, I was facing my first request for assistance to shorten the life of a patient.

That week, I was the attending physician on the palliative care service. Since palliative care medicine focuses on the treatment of all forms of suffering in serious illness, my colleague assumed that I would know what to do with this request. I didn’t.

I could see my own discomfort mirrored in his face. “Can you help us with it?” he asked me. “Of course,” I said. Then I felt my stomach lurch.

California’s law permits physicians to prescribe a lethal cocktail to patients who request it and meet certain criteria: They must be adults expected to die within six months who are able to self-administer the drug and retain the mental capacity to make a decision like this.

Continue reading the main story

But that is where the law leaves off. The details of patient selection and protocol, even the composition of the lethal compound, are left to the individual doctor or hospital policy. Our hospital, like many others at that time, was still in the early stages of creating a policy and procedure. To me and many of my colleagues in California, it felt as if the law had passed so quickly that we weren’t fully prepared to deal with it.

That aside, the idea of hastening death is uncomfortable for many doctors. In its original version, the Hippocratic oath states, “I will not administer poison to anyone when asked to do so, nor suggest such a course.” The American Medical Association, the nation’s largest association of doctors, has been formally opposed to the practice for 23 years. Its ethical and judicial council has recently begun to study the issue further.

At a dinner shortly after the law went into effect, I polled 10 palliative care colleagues on their impressions of it. There was a chorus of groans. Like me, they were being asked about it with increasing frequency, yet hadn’t found an answer that felt right. It wasn’t necessarily that we disapproved, but we didn’t want to automatically become the go-to people on this very complex issue, either.

This first patient of mine was not a simple case. When I walked into his room, he glared at me. “Are you here to help me with this aid-in-dying thing?” he asked. He was in his early 60s, thin and tired, but in no obvious distress. From my read of his chart, he met all criteria to qualify. Terminal illness, decision-making capacity, ability to self-administer the medications. And he had made the requisite first request for the drugs two weeks earlier, as procedure dictates.

When I asked why he wanted to end his life early, he shrugged. “I’m just sick of living.” I asked about any symptoms that might lie behind his request: unrelenting pain, nausea, shortness of breath. He denied them all. In palliative care, we are taught that suffering can take many forms besides the physical. I probed further and the floodgates opened.

He felt abandoned by his sister. She cared only about his Social Security payments, he said, and had gone AWOL now that the checks were being mailed to her house. Their love-hate relationship spanned decades, and they were now on the outs. His despair had given way to rage.

“Let’s just end this,” he said. “I’m fed up with my lousy life.” He really didn’t care, he added, that his sister opposed his decision.

His request appeared to stem from a deep family wound, not his terminal illness. I felt he wanted to punish his sister, and he had found a way to do it.

At our second meeting, with more trust established, he issued a sob, almost a keening. He felt terrified and powerless, he said. He didn’t want to live this way anymore.

I understood. I could imagine my own distress in his condition — being shuttled like a bag of bones between the nursing home and the hospital. It was his legal right to request this intervention from me. But given how uncomfortable I was feeling, was it my right to say no?

In the end, he gave me an out. He agreed to a trial of antidepressants. “I’ll give you four weeks,” he said. He would follow up with his primary care doctor. I couldn’t help feeling relieved.

The patient died in a nursing home, of natural causes, three months later. And I haven’t had another request since. But the case left me worried. What if he had insisted on going through with it?

I’ll admit it: I want this option available to me and my family. I have seen much suffering around death. In my experience, most of the pain can be managed by expert care teams focusing on symptom management and family support. But not all. My mother is profoundly claustrophobic. I can imagine her terror if she were to develop Lou Gehrig’s disease, which progressively immobilizes patients while their cognitive faculties remain largely intact. For my mother, this would be a fate worse than death.

But still. I didn’t feel comfortable with the idea of helping to shorten the life of a patient because of depression and resentment. In truth, I’m not sure I am comfortable with helping to intentionally hasten anyone’s death for any reason. Does that make me a hypocrite?

I realized it was past time to sort out my thinking and turned to the de facto specialist in our area on this issue for counsel. Dr. Lonny Shavelson, an emergency medicine and primary care physician in Northern California, has been grappling with the subject for many years.

Given his interest in the topic, Dr. Shavelson felt a personal obligation to ensure that this new practice would be carried out responsibly after the law was passed. He founded Bay Area End of Life Options, a consulting group that educates physicians, advocates on patients’ behalf and prescribes the lethal concoction for some patients who meet the criteria for participation.

He has devised a process for his patients that not only adheres to the letter of the law, but goes far beyond it. His patient intake procedures are time-consuming and include a thorough history and physical, extensive home visits, a review of medical records and discussions with the patients’ doctors. He assesses the medical illness, the patient’s mental and emotional state and family dynamics.

He does not offer the medications to most of the patients who request them, sometimes because he deems them more than six months away from death or because he is worried that they have been coerced or because he believes that severe depression is interfering with their judgment. Since starting his practice, he has been approached by 398 patients. He has accepted 79 of those into his program and overseen ingestion and death for 48.

Dr. Shavelson’s careful observations have made him something of a bedside pharmacologist. In his experience, both the medications used and their dosages should be tailored to individual patients. While all patients enter a coma within minutes of ingesting the lethal cocktail, some deaths take longer, which can be distressing for the family and everyone else involved. One of his patients, a serious athlete, experienced a protracted death that Dr. Shavelson attributes to the patient’s high cardiac function. After that experience, Dr. Shavelson began to obtain an athletic history on every patient, and to add stronger medications if indicated.

In another patient, a mesh stent had been deployed to keep his intestines from collapsing. This stent prevented absorption in key areas, slowing the effect of the drugs and prolonging his death. Dr. Shavelson now routinely asks about such stents, something that a doctor less experienced in this process might miss.

Dr. Shavelson strives to mitigate all symptoms and suffering before agreeing to assist any patient in dying. He recounted many cases where patients no longer requested the medications once their quality of life improved. He counts these cases among his greatest successes. This demonstrates that his commitment is to the patient, not the principle.

When I asked Dr. Shavelson how he might have proceeded with my patient, he said he would have tried everything to relieve his distress without using the lethal medication. But if in the end the patient still wanted to proceed, he would have obliged, presuming his depression was not so severe as to impair his judgment. “I don’t have to agree with a patient’s reasoning or conclusions,” he said. “Those are hers to make, just as much as turning down chemotherapy or opting not to be intubated would be.”

I recently called colleagues at other hospitals to learn how they were handling this law. Like me, most of them hadn’t yet had much experience with it, but their involvement has mostly been positive. They described the few cases they had handled as “straightforward” — patients had carefully thought through the decision and had full family support. Most patients were enrolled in hospice care and supported throughout the ingestion process by trained personnel, almost always in their homes. My colleagues reported that they were free to opt out of the program if they were uncomfortable prescribing the medications. (Catholic health systems do not participate.)

Dr. Meredith Heller, director of inpatient palliative services at Kaiser Permanente San Francisco, said that while she understood my ambivalence, she herself felt significantly better about it than she had expected to. “Surprisingly, the vast majority of cases here have gone smoothly,” she told me.

A little over a year after the law went into effect, I am heartened by the positive responses I am hearing from my colleagues around the state. I am relieved that most cases seem straightforward. I am grateful that there are dedicated physicians like Dr. Shavelson willing to do this work. And I am reassured by the knowledge that patients in California now have the legal right to exercise this power when they feel there is no other path.

But I am also concerned. As our population continues to grow older and sicker and more people learn that this law exists, we will need a highly trained work force to steward patients through this process.

My patient deserved an evaluation by a physician like Dr. Shavelson, not someone like me, with no training in this area and ambivalence to boot. We need formal protocols, official procedures, outcome measurements, even a certificate of expertise issued by an oversight board. None of these are in place in any participating state, according to Dr. Shavelson. Yet all medical procedures require training. Why should one this weighty be an exception?

What about payment? Providers can bill for an office visit and the cost of the medication. But because there are no specific codes established for this procedure, reimbursement doesn’t come close to covering any effort to do this well. On top of that, many insurers won’t cover it, including federal programs like Medicare and the Veterans Health Administration.

And will this new “right” be available to everyone? Most communities won’t have a Dr. Shavelson, who offers steep discounts to low-income patients. I worry that public hospital patients like mine will not be able to afford this degree of care. These are inequities we must address.

THERE is another question I feel compelled to raise. Is medical aid in dying a reductive response to a highly complex problem? The over-mechanization of dying in America has created a public health crisis. People feel out of control around death. A life-ending concoction at the bedside can lend a sense of autonomy at a tremendously vulnerable time.

Yet medical aid in dying will help only a tiny fraction of the population. In 2016, just under four-tenths of 1 percent of everyone who died in Oregon used this option. Other approaches such as hospice and palliative care, proven to help a broad population of patients with life-limiting illness, are still underused, even stigmatized. The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends that patients with advanced cancer receive concurrent palliative care beginning early in the course of disease. In my experience, far too few of these patients actually get it.

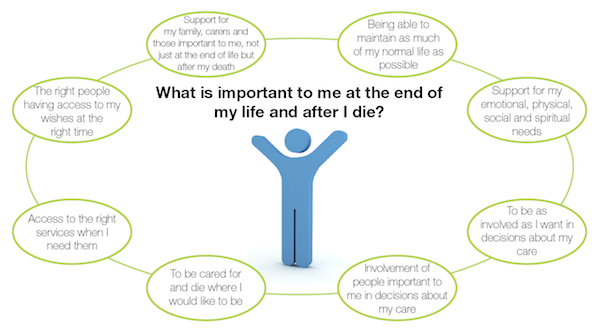

Unlike medical aid in dying, which will be used by a small proportion of the population, palliative interventions can improve the lives of many. My patient hadn’t been seen by a palliative care physician before he made his request. Although recommended, it isn’t required by law. And yet this input gave him another option.

Medical aid in dying is now the law in my home state, and I am glad for that. But our work is just beginning. We must continue to shape our policies and protocols to account for the nuanced social, legal and ethical questions that will continue to arise. We must identify the clinicians who are best qualified and most willing to do this work and then train them appropriately, not ad hoc. And we must remember that this is just one tool in the toolbox of caring for the dying — a tool of last resort.

Complete Article HERE!