by Sandy Bauers

[T]oo often, we put off the discussion. It’s too uncomfortable.

Then, suddenly, a parent or spouse is in the emergency room, and the doctors need to know: The outlook is bleak. How aggressive should they be in their treatment? What would your loved one want?

Then, suddenly, a parent or spouse is in the emergency room, and the doctors need to know: The outlook is bleak. How aggressive should they be in their treatment? What would your loved one want?

In September, Netflix released a documentary, Extremis, that aimed to bring the issue to a wide audience.

It struck a chord with Meredith MacKenzie, an assistant professor at the Villanova University College of Nursing, who specializes in end-of-life health-care issue. She recently spoke to us about it.

You watched the film. Was it good?

It was a good representation of just what these conversations look like in the intensive-care unit, or in a hospital setting in general.

I think most people think they are either going to be walking down the street one day and have a massive heart attack and keel over and die, or they are going to go to sleep one night and never wake up. Here’s the problem with that: Especially among older Americans, a very, very small number are going to die suddenly. Most are going to die in a longer, more drawn out process. You’re going to get sick, but it won’t be clearly obvious that you’re going to die right away. You’ll have this gradual decline. Over half of Americans will die in the hospital setting. Among those 65 and older, more than a fifth will die in the ICU.

But ICUs and hospitals in general are not good places for decision making. They are really crowded, really noisy. Alarms are going off. Machines are beeping. Carts are being wheeled by in the hallway. You’ve got nurses and doctors coming in and out. People need to start thinking about this before getting to the hospital, before the ICU.

The film showed how everyone struggles with this. One physician said, “Your mother is unlikely to wake up. Even if she does wake up, it is not going to be a great quality of life.” Those conversations are hard. They’re hard for families. They’re hard for doctors. They’re hard for nurses. And they’re hard for patients.

Let’s talk about the families.

As the film was closing, we heard the endings of the patient. But we never heard the ending for the loved ones, the family. My research is focused on family caregivers because they are the survivors of end-of-life care. How end-of-life care went has profound effects for a family. The likelihood of depression, suicide, guilt over what happened, it all hinges on what happened those last few weeks or days of life.

Family members in the ICU are terrified they are going to make the wrong decision. They have to keep living and think about the decisions they made, in some cases agonize over the decisions they made. Sometimes, they opt to do everything because they are afraid they are going to have to live with “Did I kill my mom? Would a miracle have happened?” Or, on the flip side, I’ve had family members who have done everything and then say, “I feel like at the end that we were torturing her.” That is a lot to live with.

What about your own journey through this?

I started out in the ER. I did not want to research end-of-life. My job was to save people’s lives. But I really struggled with seeing patients for whom we went to extreme measures to “save their lives.” I will never forget my first code in the ER. The patient was brought in by ambulance. We worked the code for 45 minutes and finally got a heartbeat back. And we were all celebrating. But I remember having this sinking feeling: He had been unconscious for so long. He was in the ICU for six days and ended up dying without ever regaining consciousness. I remember thinking: Did we do the right thing? He had tubes down his throat, multiple lines in his veins, a catheter, a feeding tube. He was on a ventilator. We had also done chest compression, so his ribs were broken, his chest was bruised, his face was bruised. I don’t know that we did the right thing.

Now, I work with a lot of older adults, many with heart failure, which is a really common diagnosis. One in five will die in a year. I start the conversation by asking them, “What is the most important thing in life? How do you spend your day? If you could not do that, would life still be worth it to you?”

I had one older gentleman who spent most of his time sitting at the kitchen table, drinking tea, chatting with his wife, seeing children and grandchildren or neighbors. This was very important to him. I said to him, “You are going to get sicker. I want to talk about at what point might you say you don’t want to go to the hospital anymore?” He said, “I don’t know that I do. I hate the hospital. I never get sleep. They limit visits.” So I said we could talk about other alternatives.

He lived a good three years, a little longer. And he passed away with hospice at home. In his last six months, he had a couple episodes that we managed, symptom-wise. He ended up with, as far as deaths go, a pretty good death. He was able to talk with family and hang out at the kitchen table up to the end.

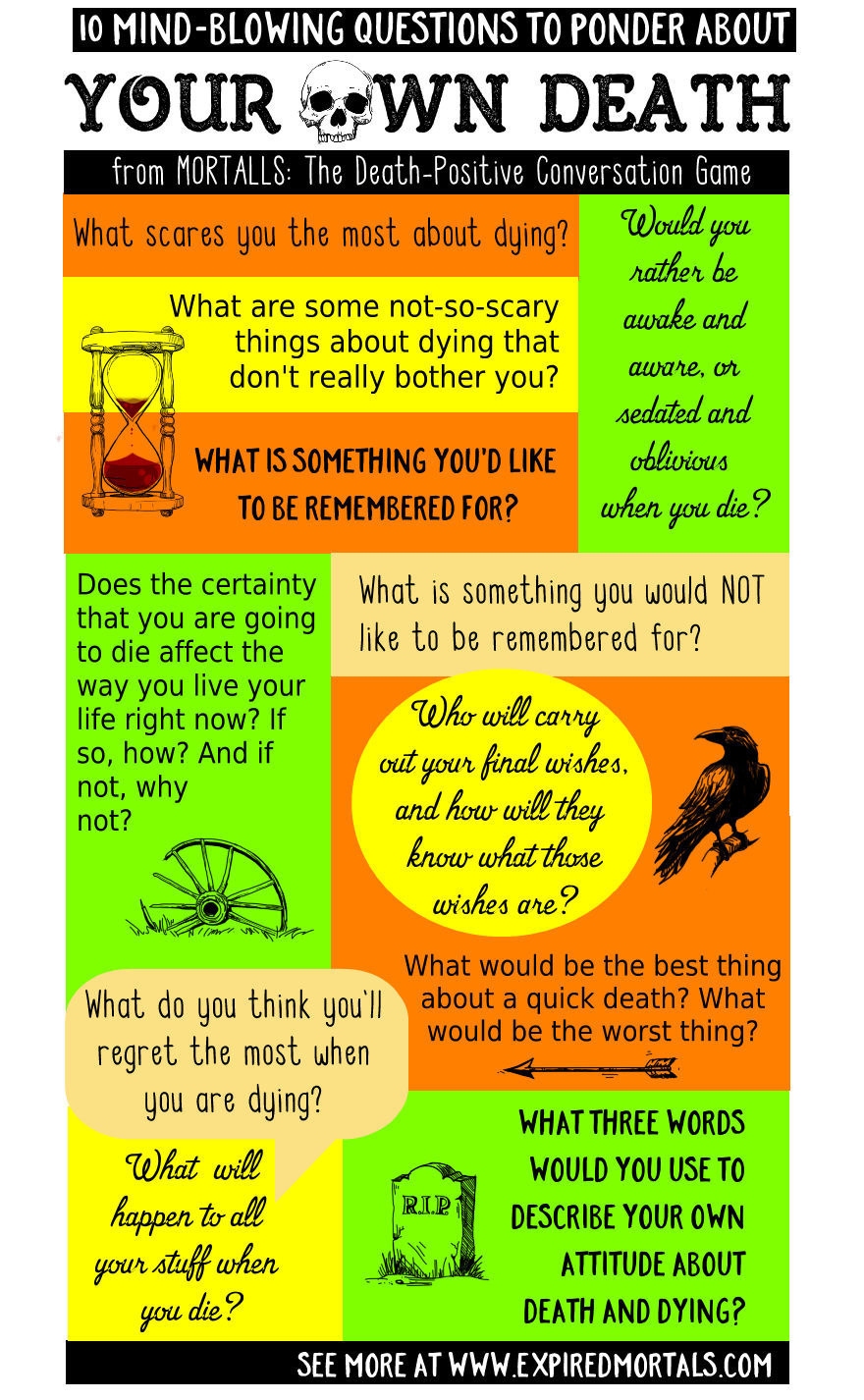

So, more people should have advance directives and living wills?

For the last 20 years, we have been on a major kick to get people to complete advance directives. We have done a semi-good job. Among Americans 65 and older, about 45 percent have completed advance directives. That’s the good news.

But there have been a couple interesting studies showing that even among people who have completed advance directives, if you ask them if they have shared it with their primary care provider? No. Have you talked about it with your family? Well, no. There is a big difference between having that piece of paper and anyone else knowing about it.

The second challenge is that most advance directives, including the Pennsylvania official form, have wording that says “if you are in a state of permanent unconsciousness . . .” Here’s the thing: When does your health-care provider know you’re in a permanent unconscious state? Families say to me, “Is our mom ever going to wake up?” I can give them some percentages. Can I ever say with absolute certainty this person is never going to wake up? Until they’re dead, that’s a tough call.

This has all been rather grim. Any encouraging words?

It is true that over half of Americans die in the hospital. But there’s the other almost half who die at home, who die in an assisted-living facility. I think what people need to know is that it is possible to have a meaningful, peaceful, symptom-controlled death outside the hospital. It is possible to give yourself the time you need to say the things you need to say and to have the experience you might want to have. For patients who opt for hospice, they actually live longer than patients who decide to have aggressive care. It’s one of the odder things of life.

It’s not about letting someone die. It’s about acknowledging that death is inevitable. No one can cheat death forever, but we can have some say in how it happens.

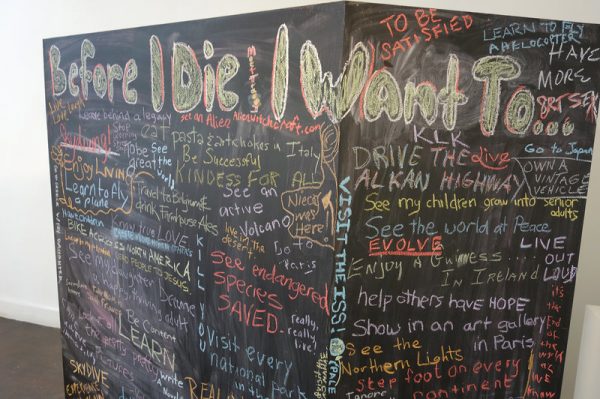

One of the most important things is, talk to your loved ones. Talk about what is meaningful in your life. Talk about what you might want, what you might not want. Watch that film and think about, if I was in the ICU, would I want a breathing tube? If you have a chronic illness, at what point would you say, “I might not want to pursue aggressive care”?

It’s hard to think about this when you’re healthy. But that is the time to do it. No matter how uncomfortable talking about dying is, dying without talking about it is more uncomfortable. Think about it as a gift you give to people who have to make those decisions.

Complete Article HERE!