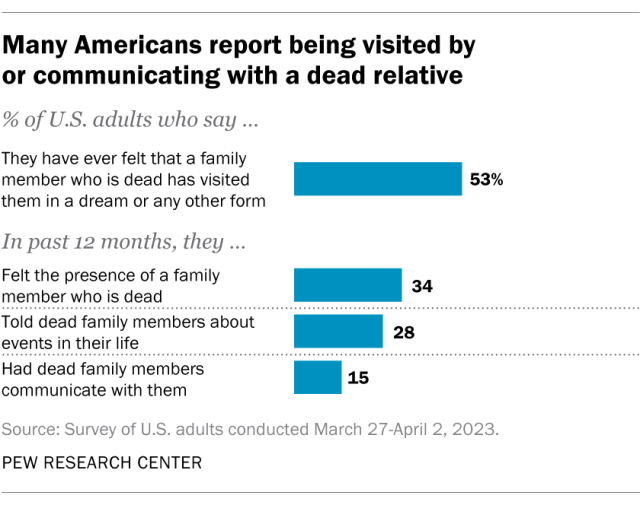

Many Americans report that their relationships with loved ones continue past death in some way, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

Around half of U.S. adults (53%) say they’ve ever been visited by a dead family member in a dream or some other form. And substantial shares say they’ve had interactions with dead relatives in the past 12 months:

- 34% have “felt the presence” of a dead relative

- 28% have told a dead relative about their life

- 15% have had a dead family member communicate with them

In total, 44% of Americans report having at least one of these three experiences in the past year.

Women are more likely than men to say they have had these kinds of interactions with dead family members. And people who are moderately religious are more likely than others – including those who are highly religious and those who are not religious – to have experienced these things.

The survey was conducted March 27-April 2, 2023, among 5,079 adults on the Center’s American Trends Panel. It included Americans of all religious backgrounds, including Jews, Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus. But there are not enough respondents from these smaller groups to report on their answers separately.

While the survey asked whether people have had interactions with dead relatives, it did not ask for explanations. We don’t know whether people view these experiences as mysterious or supernatural, or whether they see them as having natural or scientific causes, or some of both.

For example, the survey did not ask what respondents meant when they said they had been visited in a dream by a dead relative. Some might have meant that relatives were trying to send them messages or information from beyond the grave. Others might have had something more commonplace in mind, such as having dreamt about a favorite memory of a family member.

Experiences with being visited by a dead relative

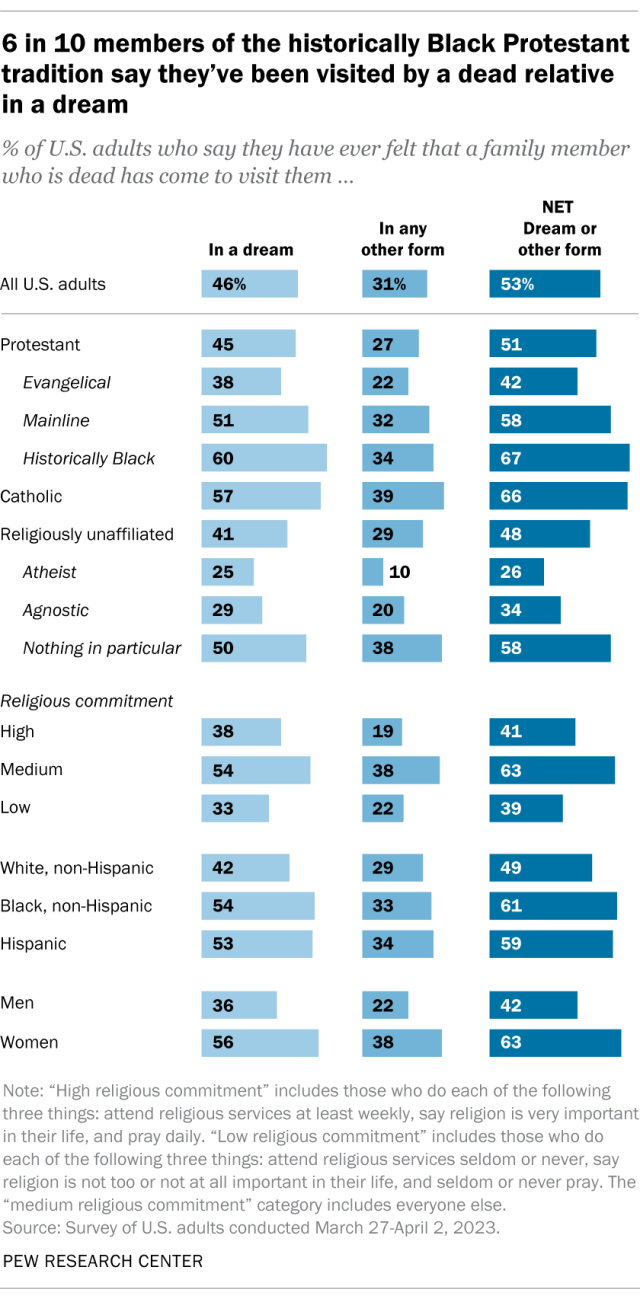

Overall, 46% of Americans report that they’ve been visited by a dead family member in a dream, while 31% report having been visited by dead relatives in some other form.

Roughly two-thirds of Catholics (66%) and members of the historically Black Protestant tradition (67%) have ever experienced a visit from a deceased family member in some form. Evangelical Protestants are far less likely to say the same (42%).

Roughly half (48%) of Americans who are religiously unaffiliated – atheists, agnostics, and those who report their religion is “nothing in particular” – say they have ever been visited by a dead relative in a dream or other form. However, those who describe their religion as nothing in particular are much more likely to say they have ever been visited by a deceased loved one (58%) than are agnostics (34%) and atheists (26%).

Recent contact with deceased relatives

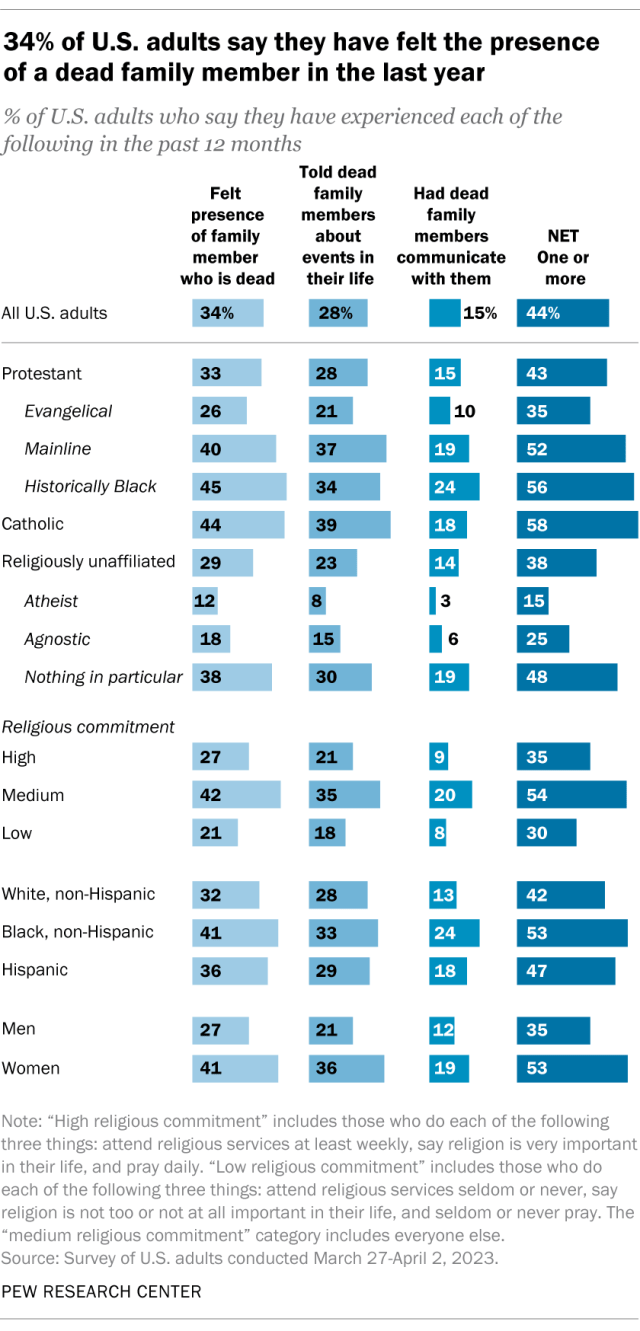

When asked about recent experiences – things that have happened in the last 12 months – 34% of Americans say they have felt the presence of a dead family member and 28% say they have told dead family members about events in their life. Fewer respondents (15%) say a deceased family member has communicated with them in the past year.

Women are more likely than men to say they had at least one of these three experiences in the last year (53% vs. 35%). For example, women are more likely than men to say they recently have felt the presence of a dead family member (41% vs. 27%).

When it comes to religion, about half or more of Catholics (58%), members of the historically Black Protestant tradition (56%) and mainline Protestants (52%) say they have had at least one of these three experiences in the last year – significantly more than the 35% of evangelical Protestants who say the same.

Relatively few atheist (15%) or agnostic (25%) adults report any of these experiences over the last 12 months. In contrast, roughly half (48%) of those who say their religion is nothing in particular reported one of these experiences.

These experiences also differ by Americans’ religious commitment, as measured by a scale that includes indicators of religious service attendance, prayer frequency and self-assessments of religion’s importance in one’s life.

Americans with medium levels of religious commitment are more likely than those with either higher or lower levels of religious commitment to say they’ve felt the presence of a family member who is dead, told a dead family member about events in their life, and felt a dead relative communicate with them in the past year.

Summing up this pattern in another way: People who are moderately religious seem to be more likely than other Americans to have these experiences. This is partly because some of the most traditionally religious groups – such as evangelical Protestants – as well as some of the least religious parts of the population – such as atheists and agnostics – are less likely to report having interactions with deceased family members.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

More and More, I Talk to the Dead

After my mother died so suddenly — laughing at a rerun of “JAG” at 10 p.m., dying of a hemorrhagic stroke by dawn — I dreamed about her night after night. In every dream she was willfully, outrageously alive, unaware of the grief her death had caused. In every dream relief poured through me like a flash flood. Oh, thank God!

Then I would wake into keening grief all over again.

Years earlier, when my father learned he had advanced esophageal cancer, his doctor told him he had perhaps six months to live. He lived far longer than that, though I never thought of it as “living” once I learned how little time he really had. For six months my father was dying, and then he kept dying for two years more. I was still working and raising a family, but running beneath the thin soil of my own life was a river of death. My father’s dying governed my days.

After he died, I wept and kept weeping, but I rarely dreamed about my father the way I would dream about my mother nearly a decade later. Even in the midst of calamitous grief, I understood the difference: My father’s long illness had given me time to work death into the daily patterns of my life. My mother’s sudden death had obliterated any illusion that daily patterns are trustworthy.

Years have passed now, and it’s the ordinariness of grief itself that governs my days. The very air around me thrums with absence. I grieve the beloved high-school teacher I lost the summer after graduation and the beloved college professor who was my friend for more than two decades. I grieve the father I lost nearly 20 years ago and the father-in-law I lost during the pandemic. I grieve the great-grandmother who died my junior year of college and the grandmother who lived until I was deep into my 40s.

Some of those I grieve are people I didn’t even know. How can John Prine be gone? I hear his haunting last song, “I Remember Everything,” and I still can’t quite believe that John Prine is gone. Can it properly be called grieving if the person who died is someone I never met? Probably not. But when I remember that John Prine will never write another song, it feels exactly like grief.

In any life, loss piles on loss in all its manifestations, and I find myself thinking often of the last lines of “Elegy for Jane,” Theodore Roethke’s poem about a student killed when she was thrown from a horse: “Over this damp grave I speak the words of my love: / I, with no rights in this matter, / Neither father nor lover.”

Why, when we grieve, can it feel so urgent to make others understand the depth of our loss, even when we have no rights in the matter? I think it must be because people so often fail to honor grief at all. We talk of “processing” loss, of reckoning with it and moving on, as though bright life could not possibly include an unvanquishable darkness. Our culture persists in treating mourning as an unpleasant process we are obliged to endure while waiting for real life to restore itself.

But God help anyone who appears to move on too quickly, or too slowly, for the grief police will be coming for them. They may be accused of giving their late spouse’s clothes away too soon, or of mourning excessively a relationship that seems too far down the grief ladder to justify such a response. People have opinions about how others should manage loss.

Just before my mother died, I heard her say to a stranger, “My husband died nine years ago, and every night I tell God I’m ready to see him again.” Four days later, she got her wish.

I’m in no hurry to join my beloved dead, but like my mother before me, I am spending more and more of my days in their company. As my father was dying, and taking so long to die, I feared that the memories of his brutal last years would overwhelm four decades of happy times. I worried that the father who followed me into my own old age would be the fretful, pain-wracked old man and not the loving optimist who had always been my surest source of strength in an indifferent world.

It didn’t turn out that way. Next month he will have been gone for 20 years, but he is as real to me today as he was on any day of the 41 years we shared on this side of the veil.

I read a newspaper article reporting that NASA will be dismantling the Saturn rocket that rises above the Alabama welcome center on I-65 South, and I remember the model Saturn rocket, taller than my 10-year-old self, that Dad and I built together from chicken wire and papier-mâché. I hear a Cole Porter song on the radio, and I remember my parents dancing in the living room. I see a blue jay perched in the pine tree just outside our family room, and I recall how often I was told that “blue jay” is the first bird I learned to call by name. There were so many blue jays in so many pine trees back in those days when I was still a cherished late-born child, and my parents were still explaining the world to me.

It’s the same with all my lost beloveds. Reminders take every possible form — the feel of pine needles underfoot, the scent of a passing woman’s perfume, the tail end of a song on a coffee shop radio, a letter tumbling out of a long-unopened book, the taste of boiled peanuts, salty and warm. The reminders loop between past and present, between one lost loved one and another, a buzzing sweep of sensations and memories and time. I keep searching for the right metaphor to convey what I mean. Is it like a braid? A web? A shroud?

Finally the word comes to me: It’s a conversation. Every day, all day long, everyone I’ve ever loved is gathered around the same table, talking.

Ten years on, I rarely dream about my mother anymore, but in the dreams where she does appear, it’s the same as before — the ordinariness of life, the rush of relief I feel, her blithe unawareness of my suffering. I walk in the door, and there she is, there they all are, no happier to see me than they would be if I’d only walked in from another room in the same house. In my dreams, as in my waking life, the dead are still here, still talking to me.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

14 Common Dreams About Dying

— And What They All Mean

Everyone has had a dream about dying at least once. Regardless of the cause of this dream about death, the whole concept of dreaming of dying is one of the most common nightmares people have.

Oddly enough, it’s also one of the most perplexing scenarios out there. But, believe it or not, dreams about dying don’t always imply death in a literal sense.

What does it mean when you dream about death and dying?

While dreams like this don’t mean you will die in real life, these dreams could mean a bunch of different things, all depending on the circumstances of the dream itself.

And despite feeling pretty ominous, many cultures believe that randomly dreaming of your death could be a sign that your death has died. In other words, it could be a sign that your fate changed for the better and that you’ll live a longer life.

In general, a dream about dying and death symbolizes inner changes, transformation, anxiety, discovery and positive development, and a fresh start. These dreams symbolically also relate to fear of the unknown, built-up resentment, grief, and trying to cope with your own mortality.

Death is a heavy subject, and it’s one that can take a lot of forms. For many people, death shows itself as a major loss. When we say something inside us died, we mean that it’s gone for good, and it’s rarely ever meant in a good way. As a result, a lot of the psychological dream interpretations about dying often will reflect this.

In many cases, having a nightmare about a family member, spouse, friend, or child dying can mean that you are afraid of losing them. It can also suggest that you may be harboring anxiety about the way they are changing, suggesting that you want them to remain the way they were when you first met them.

But there are also rage-related reasons why you might be dreaming about dying, too. Dreams of people dying can also suggest underlying anger or disappointment in some aspect of life. (It’s not unheard of, for example, for people who were victims of abuse to have dreams of their abusers dying pretty gruesome deaths.)

In some cases, dreaming of your own death could also be your brain’s way of giving you a metaphor for the way people abused you. People who are mistreated by others often will have dreams of themselves dying as a result of feeling useless or emotionally destroyed.

Above all, most dream analysts tend to see death dreams as a sign of confronting change.

The only thing that remains constant in life is change — and that might be why common dreams involve dying. This type of dream often represents a very final end and a brand new beginning. If you have recently undergone drastic changes in your life, this is the most likely reason why you’re dreaming of dying.

Adds Greg Mahr, MD, psychiatrist, author of “The Wisdom of Dreams,” and director of Consultation Liaison Psychiatry at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, “Dreams about dying are usually not literally about you dying; they are about an aspect of yourself dying, perhaps even an aspect that needs to die.”

The best way to figure out what your dream means is to take a look at your life to get a clue about what it could be. Death dreams often come as a result of having some tumultuous events in your life or are due to anxieties that could be causing you emotional distress.

Each dream is different, so it’s worth trying to figure out what the dream’s symbolism means to you.

What It Means If You Dream About Yourself Dying

Some people tend to have recurring dreams or nightmares about their own death. And while it can be a bit scary, this dream is actually a sign of change in your waking life.

This transitional phase will help you redirect your energy source and focus it more on your own mental health and well-being, rather than wasting it on others while neglecting yourself.

What It Means If You Dream About A Parent Dying

Generally, a dream about a parent dying acts as a wake-up call to focus your attention on how you approach life. This dream also indicates that you are experiencing stress and need to find a way to lessen it.

Dreaming about your father dying means you’ve been holding back from expressing your emotions, or that you are entering a new phase of the relationship with your parents, one based on comfort and support.

Dreaming about your mother dying relates to personal transformation, your own indecisiveness, or even missing a motherly figure in your life.

What It Means If You Dream About A Sibling Dying

Any dream about a loved one dying can be horrifying, and that’s especially true if you dream of a brother or sister passing away.

A sister dying in your dream indicates that you may have personal conflict with your close friends or family in real life, and need to take steps to remedy the situation.

If you dream of a brother dying, it is symbolic of the “death” of a brotherly friendship in your life, so it’s important to consider how you may be neglecting your friendships and, as a result, letting them die.

What It Means If You Dream About A Pet Dying

We all wish our furry friends could be with us forever, but part of owning a pet is realizing their mortality.

To dream about a pet dying relates to your desire to be a child again, not having to deal with the constant changes and responsibilities of adulthood. This dream can also indicate your need to step out of your comfort zone and try new things to become a more well-rounded person.

What It Means If You Dream About A Friend Dying

To dream about a friend dying indicates that you’re experiencing a change in a real-life friendship. Or, says Mahr, “If a dream is about a friend or lover dying, think about what aspect of you that person represents and how that aspect of you may be dying. That could be good or bad.”

Depending on how they appear in the dream, this determines the way you see them. In other words, those negative personality traits they have are “dying” in the waking world, as is your friendship with them.

What It Means If You Dream About A Child Dying

In general, the death of a child in your dream is about your own inner child and getting stuck in the struggles of daily life, meaning you aren’t spending time nurturing yourself.

If you dream about your own child dying, this also relates to your inner child, though it focuses more on trauma from the past, and moving on to live a better and brighter future.

Additionally, “Children are often potential, so a dream about a child dying may express a concern that a potential within you is dying,” adds Mahr.

What It Means If You Wake Up Before Dying In A Dream

Many times, people will have dreams about their own deaths; however, sometimes, they wake up right before they are about to die. Dream experts say that waking up before dying in a dream means our minds simply don’t know what lies beyond life, so we are unable to have that experience.

What It Means If You Dream About Dying From Suicide

Though suicide is a very serious subject, to dream about yourself dying from ending your life means there is some aspect of your life that you want to end. It could be a relationship, a career, or something else entirely.

What It Means If You Dream About A Boyfriend Dying

If you dream about your boyfriend dying, it means your relationship in the waking world is changing, both in the positive and negative sense. It could be that you two are simply drifting apart, that his behavior isn’t what it used to be, or that you will soon take the next step in your relationship.

What It Means If You Dream About A Girlfriend Dying

Similar to a boyfriend-involved death, dreaming of a girlfriend dying is your subconscious mind worrying about losing your partner. This dream also indicates that you may not want to be in the relationship anymore and wish to “free” yourself from its constraints.

What It Means If You Dream About A Stranger Dying

While many dreams about death involve people we know, sometimes we may dream of a complete stranger. This dream is a positive sign, however, and means that you will soon come into financial wealth. It can also indicate that you need to slow down and take your time making an important decision.

What It Means If You Dream About Dying In A Car Accident

If you dream about dying in a car crash or accident, this dream symbolizes the need to express your emotions. You may be holding them back for one reason or another, so consider it a sign to let it all out.

This dream can also mean that you must face your daily problems head-on, or that you need to approach life in a different way.

“Cars are usually symbols of the ego, of how we get around in the world. Car accident dreams are often a warning to be less reckless, to live more slowly and thoughtfully,” Mahr comments.

What It Means If You Dream About Dying From Drowning

Because dreams about water relate to emotions, dreaming about drowning means you’re suffering from emotional turmoil and are feeling overwhelmed as a result. This dream means you need to take the steps to overcome what you fear, and focus on renewal.

What It Means If You Dream About A Celebrity Dying

Dreaming about a celebrity dying indicates that they possess certain traits, and depending on what those traits are, it determines what they mean for you personally and how they relate to your life.

So, whether it’s their commitment to philanthropy, their talent, or even their negative attitude, it indicates that these specific qualities will soon come to an end in the real world.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What Does It Mean If You Dream About Dying?

No need to start planning your own funeral.

Fear not! Dreaming of a death or of dying doesn’t have to be literal, and it doesn’t mean you or a loved one will die! Trust me: My name is Valeria Ruelas, and I’m a bruja.

Dreams are complex and symbolic, and so it is important to identify the type of dreams you have before you get into the meaning. If you have a dream that seems significant to you, it’s important to sit with your intuitive feelings and thoughts after you wake up. You might consider keeping a dream journal and spending each morning reflecting on the meaning of your dreams. But if you wake up and think, “Hey, that was silly,” then no need to try to interpret your dream—sometimes they really are just pointless!

There are a few types of dreams you might have: Prophetic dreams, which predict the future; dreams about anxieties, which are a signal to work on managing your worries; pointless dreams, which just seem random; and dreams from your spirit guides, which may be instruction-heavy or have a moral lesson.

Now let’s get specific: If you dream about dying, what exactly does it mean?

What does it mean if I dream about myself dying?

Don’t worry: This doesn’t mean you’re going to die! To get more info, look at the way you die in your dream. If you die a violent death, then that means you should be careful and watch out for recklessness, immediate dangers, and enemies. If you have a peaceful death, look at the dream as a symbol of moving on, graduating, changing, or spiritual awakening. A dream about dying may also mean that you need to make an effort to forget a person or experience; you need to move on from something. Finally, like these dreams can sometimes have to do with trauma.

What does it mean if I dream about a family member or loved one dying?

This is one of those dreams I encourage people to ignore! However, it can also be an encouragement to leave your home, your city, or your comfort zone. Think about what’s been on your mind lately and if your dream relates.

What does it mean if I dream about a pet dying?

Like dreaming about a loved one dying, this dream may be also about sadness or feelings of abandonment. However, personally I would schedule a check-up with the vet, just in case!

What does it mean if I wake up just before I die a dream?

This type of dream could mean that you are supposed to figure something out from the clues. I would pay extra close attention to what is said in dialogue in these dreams, as they can be instructive about how you should live your life and what decisions you should make.

What does it mean if I have recurring dreams about dying?

Usually, dreaming about dying simply means that you are a worrier. It also could mean you’re not getting enough rest. It does *not* mean that you are doomed!

Books About Dream Interpretation

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

First ever recording of moment someone dies reveals what our last thoughts may be

By Jeff Parsons

What happens when we die?

Scientists may finally be in a position to answer that question after they recorded the brain waves of a patient as her life ended.

Crucially, they didn’t set out to capture this data – instead it ocurred by happenstance.

Researchers in the United States were running an electroencephalogram (EEG) on an 87-year-old man who suffered from epilepsy.

An EEG measures the electrical activity of your brain and, in this case, was being used to detect the onset of seizures.

However, during the treatment, the patient had a heart attack and died.

As such, the scientists were able to record 15 minutes of brain activity around his death. And what they found was extremely interesting.

Focusing on the 30 seconds either side of the moment the patient’s heart stopped beating, they detected an increase in brain waves known as gamma oscillations.

These waves are also involved in activities such as meditation, memory retrieval and dreaming.

We can’t say for sure whether dying people really do see their life flash before their eyes, but this particualar study seems to support the idea.

And the scientists say the brain is capable of co-ordinated activity for a short period even after the blood stops flowing through it.

‘Through generating oscillations involved in memory retrieval, the brain may be playing a last recall of important life events just before we die, similar to the ones reported in near-death experiences,’ said Dr. Ajmal Zemmar, lead author of the study, which was published in the journal Frontiers in Ageing Neuroscience.

‘These findings challenge our understanding of when exactly life ends and generate important subsequent questions, such as those related to the timing of organ donation.’

In the study, the researchers point out that similar changes in brainwaves have been detected in rats at the time of death.

However, this is the first time it’s been seen in a human.

Dr. Zemmar and his team say that further research needs to be done before drawing any definite conclusions.

This study arises from data relating to just a single case study. And the patient’s brain had already been injured and was showing unusual activity related to epilepsy.

It’s not clear if the same results would occur in a different person’s brain at the time of death.

‘Something we may learn from this research is: although our loved ones have their eyes closed and are ready to leave us to rest, their brains may be replaying some of the nicest moments they experienced in their lives,’ Dr. Zemmar said.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

‘Death Is But a Dream’

— Partnering to tell stories about the end of life

UB professor Carine Mardorossian has worked with hospice doctor Christopher Kerr on projects that explore end-of-life experiences from the perspective of both patients and caregivers

On April 15, the WORLD Channel, carried by public television stations across the U.S., will air “Death Is But A Dream,” a documentary based on a book co-authored by local hospice doctor Christopher Kerr and University at Buffalo Professor Carine Mardorossian.

The book, “Death Is But a Dream: Finding Hope and Meaning at Life’s End,” is the brainchild of Kerr, who over the course of his career noticed a pattern in patients who were near life’s end. He observed that in end-of-life stages, many people began to have dreams and visions of deceased loved ones visiting them at bedside. The dreams and visions often became more frequent as death drew near.

After researching and collecting data for over a decade, Kerr wanted to write a book which archived and told the experiences his patients were having.

The lengthy process of getting the book to where it is now, being published in 10 different languages and sold in 10 different countries, was rough at first. The timeline of how Kerr and Mardorossian came together in writing the book was “quite interesting,” says Kerr, MD, PhD, chief medical officer and CEO for Hospice & Palliative Care Buffalo.

When Kerr and his literary agent began the process, they originally sought out a different author to assist in putting Kerr’s research into meaningful words. The partnership quickly collapsed because Kerr believed that to write about subject, you would have to witness the patients’ experiences in person, which at that time, the prospective writer was unable to do.

Mardorossian, on the other hand, had been friends with Kerr for over a decade as she stabled her horse at Kerr’s barn. In passing, Kerr explained to her that he had given up on the book because finding a writer who saw eye-to-eye with him was hard to accomplish.

Mardorossian, PhD, a professor of English and of Global Gender and Sexuality Studies in the UB College of Arts and Sciences, offered her services. But as an academic writer, her style of writing was not what Kerr was looking for — initially.

“I continually said to Kerr, ‘Let me write it,’” says Mardorossian. “I’m not that type of person, I’m really not. I honestly felt like I was having an out-of-body experience, as I caught myself insisting: I had never written a book for the mainstream, yet I was so determined to write this one.”

Kerr ultimately decided Mardorossian was the right fit, and he again pursued the book. The process of writing soon began and took the duo a year and a half to complete. Kerr says Mardorossian “helped me find a much deeper meaning.”

“I talked to Christopher every single day, and we met up to five times a week, and we would work,” says Mardorossian. “It was a constant back and forth.”

Kerr added, “We took over coffee shops that they should have expelled us from. We could have opened and closed some of them.”

The partnership flourished. The book got picked up by Penguin Random House after what Mardorossian said was “a longer than usual bidding war” between seven companies.

Looking back, Kerr said that there was never an argument or tension throughout the whole process, as their egos were left behind. Kerr admires Mardorossian’s work ethic and determination, and calls the experience of working with her “the most enjoyable process.”

Mardorossian discusses the importance of Kerr’s work in, “As death approaches, our dreams offer comfort, reconciliation,” an article published in The Conversation.

“As hospitals and nursing homes continue to remain closed to visitors because of the coronavirus pandemic, it may help to know that the dying rarely speak of being alone. They speak of being loved and put back together,” Mardorossian writes. “There is no substitute for being able to hold our loved ones in their last moments, but there may be solace in knowing that they were being held.”

Mardorossian and Kerr are now writing another book which will be a “natural extension” from their first one, says Mardorossian. The new project will be from the caregiver’s perspective.

Kerr and Mardorossian want to shed light on these caregivers’ experiences because they believe the grieving process is an important part of someone’s end-of-life experience.

“Family members have to become nurses whether they know anything about nursing or not,” says Mardorossian. “The testimonies Kerr has collected from these caregivers say how it’s the hardest thing they’ve ever done, but also the best thing as well.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

As death approaches, our dreams offer comfort, reconciliation

One of the most devastating elements of the coronavirus pandemic has been the inability to personally care for loved ones who have fallen ill.

Again and again, grieving relatives have testified to how much more devastating their loved one’s death was because they were unable to hold their family member’s hand – to provide a familiar and comforting presence in their final days and hours.

Some had to say their final goodbyes through smartphone screens held by a medical provider. Others resorted to using walkie-talkies or waving through windows.

How does one come to terms with the overwhelming grief and guilt over the thought of a loved one dying alone?

I don’t have an answer to this question. But the work of a hospice doctor named Christopher Kerr – with whom I co-authored the book “Death Is But a Dream: Finding Hope and Meaning at Life’s End” – might offer some consolation.

Unexpected visitors

At the start of his career, Dr. Kerr was tasked – like any and all physicians – with attending to the physical care of his patients. But he soon noticed a phenomenon that seasoned nurses were already accustomed to. As patients approached death, many had dreams and visions of deceased loved ones who came back to comfort them in their final days.

Doctors are typically trained to interpret these occurrences as drug-induced or delusional hallucinations that might warrant more medication or downright sedation.

But after seeing the peace and comfort these end-of-life experiences seemed to bring his patients, Dr. Kerr decided to pause and listen. One day, in 2005, a dying patient named Mary had one such vision: She began moving her arms as if rocking a baby, cooing at her child who had died in infancy decades prior.

To Dr. Kerr, this didn’t seem like cognitive decline. What if, he wondered, patients’ own perceptions at life’s end mattered to their well-being in ways that should not concern just nurses, chaplains and social workers?

What would medical care look like if all physicians stopped and listened, too?

The project begins

So at the sight of dying patients reaching and calling out to their loved ones – many of whom they had not seen, touched or heard for decades – he began collecting and recording testimonies given directly by those who were dying. Over the course of 10 years, he and his research team recorded the end-of-life experiences of 1,400 patients and families.

What he discovered astounded him. Over 80% of his patients – no matter what walk of life, background or age group they came from – had end-of-life experiences that seemed to entail more than just strange dreams. These were vivid, meaningful and transformative. And they always increased in frequency near death.

They included visions of long-lost mothers, fathers and relatives, as well as dead pets come back to comfort their former owners. They were about relationships resurrected, love revived and forgiveness achieved. They often brought reassurance and support, peace and acceptance.

Becoming a dream weaver

I first heard of Dr. Kerr’s research in a barn.

I was busy mucking my horse’s stall. The stables were on Dr. Kerr’s property, so we often discussed his work on the dreams and visions of his dying patients. He told me about his TEDx Talk on the topic, as well as the book project he was working on.

I couldn’t help but be moved by the work of this doctor and scientist. When he disclosed that he was not getting far with the writing, I offered to help. He hesitated at first. I was an English professor who was an expert in taking apart the stories others wrote, not in writing them myself. His agent was concerned that I wouldn’t be able to write in ways that were accessible to the public – something academics are not exactly known for. I persisted, and the rest is history.

It was this collaboration that turned me into a writer.

I was tasked with instilling more humanity into the remarkable medical intervention this scientific research represented, to put a human face on the statistical data that had already been published in medical journals.

The moving stories of Dr. Kerr’s encounters with his patients and their families confirmed how, in the words of the French Renaissance writer Michel de Montaigne, “he who should teach men to die would at the same time teach them to live.”

I learned about Robert, who was losing Barbara, his wife of 60 years, and was assailed by conflicting feelings of guilt, despair and faith. One day, he inexplicably saw her reaching for the baby son they had lost decades ago, in a brief span of lucid dreaming that echoed Mary’s experience years earlier. Robert was struck by his wife’s calm demeanor and blissful smile. It was a moment of pure wholeness, one that transformed their experience of the dying process. Barbara was living her passing as a time of love regained, and seeing her comforted brought Robert some peace in the midst of his irredeemable loss.

For the elderly couples Dr. Kerr cared for, being separated by death after decades of togetherness was simply unfathomable. Joan’s recurring dreams and visions helped mend the deep wound left by her husband’s passing months earlier. She would call out to him at night and point to his presence during the day, including in moments of full and articulate lucidity. For her daughter Lisa, these occurrences grounded her in the knowledge that her parents’ bond was unbreakable. Her mother’s pre-death dreams and visions assisted Lisa in her own journey toward acceptance – a key element of processing loss.

When children are dying, it is often their beloved, deceased pets that make appearances. Thirteen-year-old Jessica, dying of a malignant form of bone-based cancer, started having visions of her former dog, Shadow. His presence reassured her. “I will be fine,” she told Dr. Kerr on one of his last visits.

For Jessica’s mom, Kristen, these visions – and Jessica’s resulting tranquility – helped initiate the process she had been resisting: that of letting go.

Isolated but not alone

The health care system is difficult to change. Nevertheless, Dr. Kerr still hopes to help patients and their loved ones reclaim the dying process from a clinical approach to one that is appreciated as a rich and unique human experience.

Pre-death dreams and visions help fill the void that may otherwise be created by the doubt and fear that death evokes. They help the dying reunite with those they have loved and lost, those who secured them, affirmed them and brought them peace. They heal old wounds, restore dignity, and reclaim love. Knowing about this paradoxical reality helps the bereaved cope with grief as well.

As hospitals and nursing homes continue to remain closed to visitors because of the coronavirus pandemic, it may help to know that the dying rarely speak of being alone. They speak of being loved and put back together.

There is no substitute for being able to hold our loved ones in their last moments, but there may be solace in knowing that they were being held.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!