By Parul Sehgal

“The road to death,” the anthropologist Nigel Barley wrote, “is paved with platitudes.”

Book reviewers, I’m afraid, have played their part.

The robust literature of death and dying is clotted with our clichés. Every book is “unflinching,” “unsparing.” Somehow they are all “essential.”

Of course, many of these books are brave, and many quite beautiful. Cory Taylor’s account of her terminal cancer, “Dying: A Memoir,” is one recent standout. But so many others are possessed of a dreadful, unremarked upon sameness, and an unremitting nobility that can leave this reader feeling a bit mutinous. It’s very well to quail in front of the indomitable human spirit and all that, but is it wrong to crave some variety? I would very much like to read about a cowardly death, or one with some panache. I accept, grudgingly, that we must die (I don’t, really) but must we all do it exactly the same way?

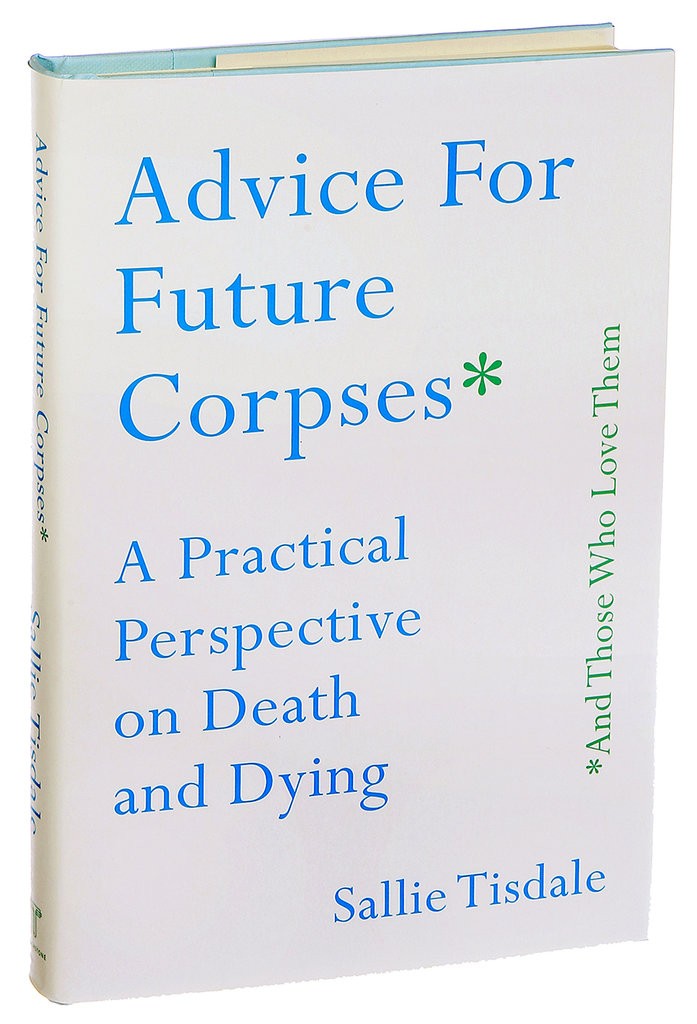

Enter “Advice for Future Corpses (and Those Who Love Them),” by the writer, palliative-care nurse and Zen Buddhist Sallie Tisdale — a wild and brilliantly deceptive book. It is a putative guide to what happens to the body as it dies and directly after — and how to care for it. How to touch someone who is dying. (“Skin can become paper-thin, and it can tear like paper. Pressure is dangerous.”) How to carry a body and wash it. How to remove its dentures.

But in its loving, fierce specificity, this book on how to die is also a blessedly saccharine-free guide for how to live. There’s a reason Buddhist monks meditate on charnel grounds, and why Cicero said the contemplation of death was the beginning of philosophy. Tisdale has written extensively about medicine, sex and faith — but spending time with the dying has been the foundation of her ethics; it is what has taught her to understand and tolerate “ambiguity, discomfort of many kinds and intimacy — which is sometimes the most uncomfortable thing of all.”

It should be noted that this book is not for the queasy. Frankly, neither is dying. Tisdale writes calm but explicit descriptions of “the faint leathery smell” of dead bodies and the process of decomposition. “A dead body is alive in a new way, a busy place full of activity,” she writes. She offers paeans to the insects that arrive in stately waves to consume the body — from the blowflies that appear in the first few minutes of death to the cheese skippers, the final guests, which clean the bones of the last bits of tendon and tissue.

This is death viewed with rare familiarity, even warmth: “I saw a gerontologist I know stand by the bedside of an old woman and say with a cheerleader’s enthusiasm, ‘C’mon, Margaret. You can do it!’” Tisdale writes. She walks readers through every conceivable decision they will have to make — whether to die in the hospital or at home, how to handle morphine’s side effects and how to breathe when it becomes difficult (inhale through pursed lips).

To the caretaker, she writes: “You are the defender of modesty, privacy, silence, laughter and many other things that can be lost in the daily tasks. You are the guardian of that person’s desires.”

“Advice for Future Corpses” also offers a brisk cultural history of death rituals and rites, from traditional Tibetan sky burials to our present abundance of options. You can have your ashes mixed into fireworks, loaded into shotgun shells or pressed into a diamond. You can ask to be buried at sea (but don’t — too much paperwork). You can be buried in a suit lined with micro-organisms and mushrooms to speed decomposition, or let a Swedish company cryogenically freeze your remains and turn them into crystals. If you’re in Hong Kong or Japan, you have the option of virtual graves, where flowers can be sent by emoticon.

Tisdale’s perspective is deeply influenced by her Buddhist practice, never more so than when she considers how the mind might apprehend death as it nears: “Consciousness is no longer grounded in the body; perception and sensation are unraveling. The entire braid of the self is coming unwound in a rush. One’s point of view must change dramatically.”

Tisdale does not write to allay anxieties but to acknowledge them, and she brings death so close, in such detail and with such directness, that something unusual happens, something that feels a bit taboo. She invites not just awe or dread — but our curiosity. And why not? We are, after all, just “future corpses pretending we don’t know.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!