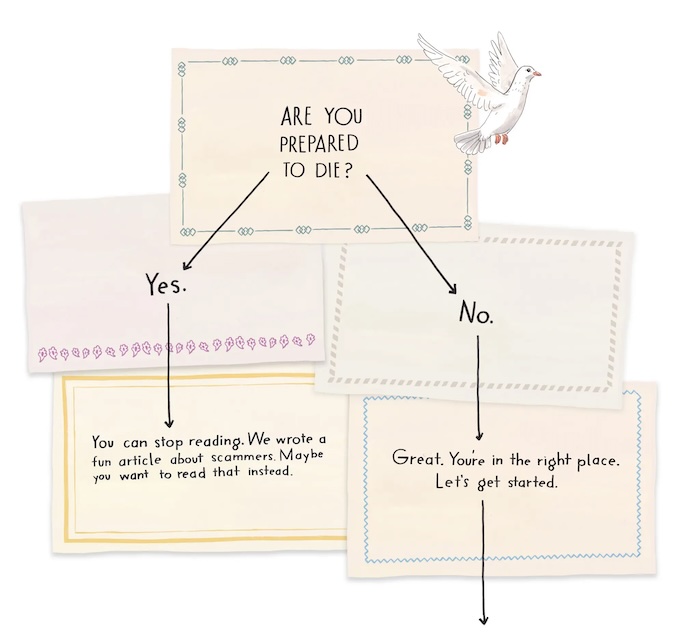

— Or the Fear of Dying, May Prevent You From Actually Living

Despite the best efforts of the death positivity movement, most people do not have a good time going to wakes or memorial services, and that’s completely normal. But for others, the thought of death—whether it’s a loved one dying or themselves—sparks intense fear and panic. “Fear is a natural and important human emotion,” says Mitchell L. Schare, PhD, ABPP, director of the Hofstra University Phobia and Trauma Clinic. But sometimes that fear of dying can be taken to extremes. “When it becomes inhibitory to living life, it becomes a phobia,” says Dr. Schare. Specifically, that phobia is known as thanatophobia, or the intense fear of death and dying.

“Fear is a natural and important human emotion. When it becomes inhibitory to living life, it becomes a phobia.” —Mitchell L. Schare, PhD, ABPP, director of the Hofstra University Phobia and Trauma Clinic

Thanatophobia (also called “death anxiety”) can be considered the “master fear,” says Dr. Schare, since so many other phobias—from fearing spiders to airplanes to illness—can be traced to a fear of death. But as with any kind of phobia, thanatophobia is more serious than just a distaste for thinking about death. It can cause avoidance of anything that might theoretically lead to death or situations in which family members or friends are dying.

There’s so much to unpack when it comes to thanatophobia. Here’s what you need to know about the fear of death, where it comes from, and how someone can cope with thanatophobia.

Is thanatophobia a mental illness?

Like other specific phobias, thanatophobia is considered a type of anxiety disorder1. According to the DSM-5-TR (aka the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the tool mental health professionals use to make diagnoses), a phobia is a “marked fear or anxiety about a specific object or situation (e.g., flying, heights, animals, receiving an injection, seeing blood).” For people with phobias (like thanatophobia), their fear or anxiety is way greater than the actual danger they face from their phobia, they go to great lengths to avoid it, and it cannot be explained by another mental health disorder.

Because thanatophobia is a type of anxiety disorder, mental health professionals will apply some of the same techniques used to treat anxiety disorders, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). (More on that in a bit!)

How common is thanatophobia?

There’s not a ton of data available on the general population, but an estimated 3 to 10 percent of people experience thanatophobia, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

Interestingly, research suggests that the prevalence of death anxiety changes with age in unexpected ways. One 2007 paper published in the journal Death Studies found that death anxiety spikes in young adults in their early ‘20s2, and then dips off. It also found that in women (but not men), death anxiety surges again in their ‘50s. While you might assume that older adults might have more fear of death (because they’re, you know, closer to the natural end of their lives), other research suggests that elderly patients have lower levels of death anxiety3 than their children.

What are the symptoms of thanatophobia?

“Thanatophobia [symptoms] can vary in prevalence depending on cultural, personal, and situational factors,” explains clinical psychologist Alexander Alvarado, PsyD, phobia specialist at Thriving Center of Psychology. Here are some of the common emotional and behavioral symptoms of thanatophobia:

- Obsessive thoughts, including checking things constantly about your health and well-being (or that of your loved ones)

- Avoidance behaviors around death or potentially dangerous situations (like refusing to drive or fly in airplanes, for example, out of fear of fatal accidents)

- Severe anxiety (like feelings of dread, panic, etc.) when thinking about death. This might manifest as physical symptoms of anxiety in the form of heart palpitations, dizziness, chills, nausea, shortness of breath, etc.

This might seem a bit confusing initially; isn’t everyone afraid of dying, at least a little bit? “Having some degree of a fear of death can be functional—it might make you drive more carefully, or take extra care of yourself when you’re sick, so you can live a better quality of life,” says Dr. Schare.

But the tipping point into death anxiety can be how the anxiety manifests. Being so afraid of being in any situation that could involve death (no matter how remote the possibility) that you isolate yourself and never go out is likely closer to thanatophobia, Dr. Schare says as an example.

What causes thanatophobia?

As with any type of anxiety disorder, thanatophobia doesn’t always have a clear-cut cause. But experts believe there are some risk factors or potential triggers worth knowing.

A history of trauma or mental illness

“There isn’t a clear medical cause of thanatophobia, but it’s believed to be related to existential concerns and possibly a history of trauma,” says Dr. Alvarado. The trauma history could be related to significant life changes, such as a personal illness or near-death experience. (This could explain, for example, why nurses and emergency-services personnel had very high levels of death anxiety4 during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic.) It’s also more likely to be prevalent in people who have a history of anxiety disorders.

Loved ones dying early

People who have experienced the death of a loved one, especially if they did not have a thorough understanding of death at that time, could be susceptible to developing thanatophobia, says clinical psychologist Tirrell De Gannes, PsyD, anxiety disorder specialist at Thriving Center of Psychology. It might be more pronounced for people who have an over-reliance on loved ones, he adds, and therefore fear what could happen if that person were to die.

Religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs

People have different religious, spiritual, and philosophical outlooks on death and what the aftermath of that process might look like, says Dr. Schare, whether that’s a spiritual “better place” that someone believes in, or a rebirth. Those beliefs might moderate the fear in some respects, he adds.

Other times, people believe in none of the above, and that doesn’t mean that they automatically have thanatophobia. It’s just that the fear of dying could be more pronounced if people emphasize the “unknown” aspect of what happens after death.

Interestingly, a 2017 meta-analysis published in the journal Religion, Brain & Behavior found the people who were least likely to have death anxiety were the atheists and the extremely religious5. “It may well be that atheism also provides comfort from death, or that people who are just not afraid of death aren’t compelled to seek religion,” said the researchers in a press release.

How is thanatophobia diagnosed?

If a mental health professional suspects you could have thanatophobia, or any phobia, the diagnosis involves clinical interviews. The therapist will ask you questions to assess how your fear (and its symptoms) impact your life, Dr. Alvarado says. They will take notes on how much death is a focus, adds Dr. De Gannes, whether or not the person has any sense of relief, and whether or not it affects their behaviors, such as isolating from other people or not participating in activities that could be a risk of injury or illness.

How is thanatophobia treated?

As with other specific phobias, thanatophobia is often treated with CBT. This research-backed practice will help patients challenge and change their negative thought patterns around death, says Dr. Alvarado.

Exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP) is a specific type of CBT that is commonly used with phobias. The goal is to help someone learn to manage their phobia by getting exposed to it gradually in a safe, controlled setting. “The goal is to reduce avoidance behaviors, and potentially introduce mindfulness practices to help cope with existential concerns,” adds Dr. Alvarado. No, this doesn’t involve seeing a dead body in therapy or something. Dr. De Gannes says a therapist might try the following exposures instead: talking about the topic of death, practicing having an end-of-life conversation with a loved one, and/or imagining consequences after the death of a relative.

ERP has varying intensities and styles, says Dr. Schare. It can be very literal, done in real-world environments. Think: a therapist taking someone who is afraid of bridges on a walk over a bridge, and speaking with them afterward to recap what happened and help the person understand that they are safe, he explains. Exposure therapy can also be done in virtual reality or imaginary environments, where the person, guided by a mental health professional, enters a scenario in which they could have a near-death experience, allowing them to confront that anxiety around it head-on.

Coping with thanatophobia

It is possible that the fear of life gets more pronounced with age, as people start to have more prominent health issues and start to become closer to death, says Dr. Schare. But the bottom line is that phobias and anxiety disorders can be cured, he says. The cognizance that you and your loved ones will die at some point does not go away, but people can become better equipped to cope with it.

Some coping strategies can include daily mindfulness, meditation, and journaling to help you stay present and focused on the here and now, as well as to process the fears, suggest Dr. Alvarado. You also might find relief and some additional coping skills from talking to other people in support groups about phobias, and of course from individual therapy.

Avoiding death and anything to do with it is not the most helpful way to cope with thanatophobia. “Shying away from the topic of death only increases the mystery and fear of it,” says Dr. De Gannes. He emphasizes that it’s important to normalize the concept of death in conversations to demystify the fear and help you continue to live your life.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!