by

[M]y cat, Osiris, is lying at my feet as I type this article. That’s his normal nook while I’m in my office, which doubles as our guest room—the futon behind me is also a suitable sleeping option. Celebrating his eighteenth birthday soon, I’m thankful he’s stayed healthy and vibrant for this long. The same was not the case for his namesake.

On Sunday many Christian faithful celebrated the resurrection of their savior. Yet the story of Christ is an oft-repeated motif in mythological literature. Resurrection tales abound across the planet. This was first brought to broader attention thanks to James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, an exhaustive survey on world mythologies that was originally written to show their inadequacies by a skeptical Frazer, yet turned out to influence entire academic departments in the comparative mythology and comparative religion fields that grew from his work.

While much speculation has been offered as to why resurrection cycles persisted, the annual birth, death, and rebirth of the soil provide an important clue. The plants that grow, wither, and die seasonally only to return to nourish us once again makes for a convenient segue to the concept of souls. Frazer consciously linked this fact with the cults of Persephone, Adonis, Attis, Osiris, and Dionysus. As he writes,

It remains to see whether the conception the annual death and resurrection of a god, which figures so prominently in these great Greek and Oriental worships, has not also its origin or its analogy in the rustic rites observed by reapers and vine-dressers amongst the corn-shocks and the vines.

Easter Sunday, known as Resurrection Sunday to the faithful, marks the third day of Christ’s burial after his death on the crucifix. Missionary Christianity spread Christ’s story across the planet; over the course of centuries those other resurrected gods were discredited, rewritten, or forgotten. The uniqueness of Christ’s story has been challenged by modern scholarship, notably by tablets such as Gabriel’s Revelation. Frazer just brought that reality to the forefront.

Unlike many older stories, the Christ motif was unlinked at some point from sexuality and regeneration to focus on the soul. This speaks in part to the establishment of Christian ethics, yet the desexualization of Christ did a disservice to our understanding of ecology and the environment. The below figures are all in some way connected to fertility and nutritional sustenance, two necessities for the continuation of life. The Christ story is mainly metaphysical, unchained from the earthly cycles even though those annual renewals provide the foundation upon which the Christian mythology was founded.

Beyond the cited figure in each historical mythology is the theme, which is essentially more relevant to the living than the dead. Sure, we discover emotional comfort by the notion of life beyond the grave, but what really matters is picking ourselves up after deaths during lifetime—divorce; the death of relatives and loved ones; losing a job; watching a child leave the nest. Our character is defined by our response to tragedy and suffering.

As the characters below demonstrate, some achieve greater glory after the tragedy while others are trapped in an unforgiving underworld for eternity. What unites them is the human imagination that dreamed up each figure to communicate a primal idea about how to navigate life.

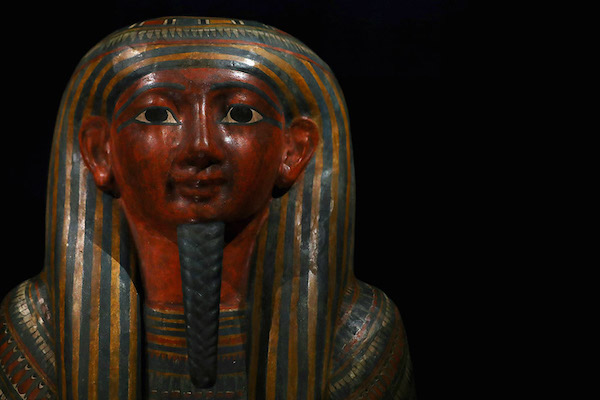

Osiris

The Egyptian deity of the afterlife, underworld, and dead is the classic tale of regeneration. There are many variations on his theme, but each poem centers around his love for his sister-wife Isis, a jealous brother that murders him, Set, and his son, Horus, who avenges his father’s death. In every variation, Isis copulates with Osiris’s briefly resurrected body before he once again perishes. In one telling, his body parts are scattered across the planet, which Isis has to collect before stitching him back together. The agricultural connection is clear: Osiris was associated with the annual flooding of the Nile River and the crops dependent upon its rising. He was also linked to the positioning of the stars, Orion and Sirius, at the beginning of each new year, another resurrection motif.

Dionysus

The Greeks offer the most famous mythological motifs in the West, unsurprisingly as they’re the basis of our culture. Maybe the drunken god of grape harvest, wine, fertility, religious ecstasy, and ritual madness waking up the morning after was enough of an impetus to make him a resurrected being—sulfites pack a punch. Dionysus was never crucified, but torn to bits by cannibalistic titans; he was somehow reshaped from the remaining heart, which flies in the face of anthropological data that our ancestors were organ eaters. Regardless, mythology is not about facts. Rituals celebrating his prowess remain beloved to this day.

Tammuz

In one of the world’s oldest pieces of literature, The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Sumerian king references Tammuz, an ancient Mesopotamian lord of shepherds, as an ex-lover of Ishtar who was turned into a bird with a broken wing. The scorching Mesopotamian summers needed a hero to resurrect the fertile soil every year—the link between sex/fertility and vegetation, noted above with Dionysus, is another common motif—and that duty fell onto Tammuz, who was also known as Dumuzid. A midsummer month was even named in his honor. Tammuz’s legacy lived behind himself, as gods do. He was incorporated into myths in the Levant and Greece, where he became known as Adonis.

Adonis

Being the mortal lover of Aphrodite is no small task. As his harbinger, Tammuz, was already firmly secure in his sexual prowess, Adonis has echoed through the generations as the ideal lover. Born from a myrrh tree and raised by Persephone, whose own myth centers on the regeneration powers of vegetation, Adonis’s good looks created a feud between Aphrodite and Persephone. Zeus declared that the boy would spend one-third of each year with each of them, then choose where to spend his final third term. He must not have been a fan of Hades, as he chose Aphrodite. Then he was gored by a wild boar, dying in Aphrodite’s arms. Adonis is reborn with gardens planted in his honor each summer, the result of his dying blood mixing with Aphrodite’s tears to form an anemone flower.

Attis

This Geek deity’s story went down over a millennia before the Christ figure appears. His first cult was linked to a Phrygian trading outpost, Pessinos, whose great mountain was thought to be a daemon. Attis’s mother, Nana, became pregnant by laying an almond from a mystical tree on her bosom. She had second thoughts about this motherhood job, though, as upon his birth she abandoned him. Attis was subsequently raised by a he-goat. He fell in love with Cybele, but his foster parents sent him to Pessinos, where he was forced into an arranged marriage to King Midas’s daughter. Eventually, he went mad and cut off his genitals, so that he would not betray Cybele. He too died and was reborn, concurrent with the spring planting and autumn harvest the locals experienced every season.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!