By Rachel Schraer

[S]cientists are expecting a spike in deaths in the coming years. As life expectancies increased, the number of people dying fell – but those deaths were merely delayed.

With people living longer, and often spending more time in ill-health, the Dying Matters Coalition wants to encourage people to talk about their wishes towards the end of their life, including where they want to die.

“Talking about dying makes it more likely that you, or your loved one, will die as you might have wished. And it will make it easier for your loved ones if they know you have had a ‘good death’,” the group of end-of-life-care charities said.

Where to die?

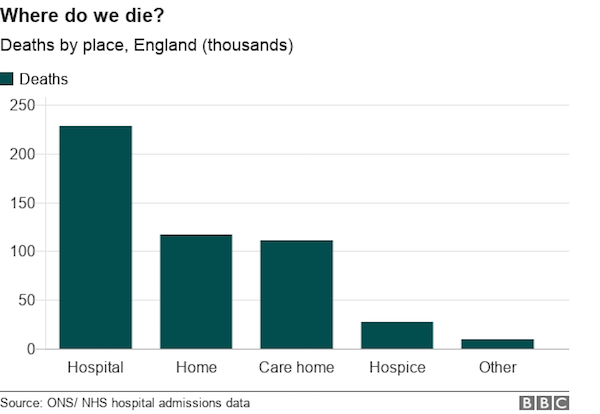

Surveys repeatedly find most people want to die at home. But in reality the most common place to die is in hospital.

Almost half of the deaths in England last year were in hospital, less than a quarter at home, with most of the remainder in a care home or hospice.

What happens to human remains?

Dying wishes don’t just extend to where you die but to what happens to your body after death too.

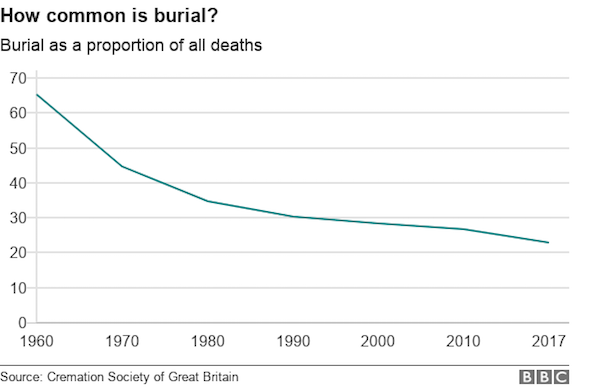

Cremation overtook burial in the UK in the late-1960s as the most popular way to dispose of human remains, and more than doubled in popularity between 1960 and 1990.

Since then it has remained fairly stable at about three-quarters of the deceased being cremated, although it has been creeping up gradually year on year – in 2017 it hit 77%.

Although cremation is thought to be more environmentally friendly, it is not without its own costs. The process requires energy. And burning bodies releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

There are hundreds of “green” burial grounds in Britain where coffins must be biodegradable and no embalming fluid or headstone markers are permitted. Instead, loved ones of the deceased often plant trees as a memorial.

The Association of Natural Burial Grounds says: “Many people nowadays are conscious of our impact on the environment and wish to be as careful in death as they have been during their lives to be as environmentally friendly as possible.”

At natural burial grounds, bodies are generally buried in shallow graves to help them degrade quickly and release less methane – a greenhouse gas.

Some people want to go further than this.

A form of “water cremation” is currently available in parts of the US and Canada, and could come to the UK.

This eco-friendly method uses an alkaline solution made with potassium hydroxide to dissolve the body, leaving just the skeleton, which is then dried and pulverised to a powder.

Sandwell Council, in the West Midlands, was granted planning permission to introduce a water cremation service, but these plans are currently on hold because of environmental concerns.

In December 2017, water providers membership body Water UK intervened and said it feared “liquefied remains of the dead going into the water system”.

Cremation by fire or burial remain the two options for most people, but those that want to do something a bit different could opt to have their ashes turned into a diamond or vinyl record, displayed in paperweight, exploded in a firework or shot into space.

The cost of death

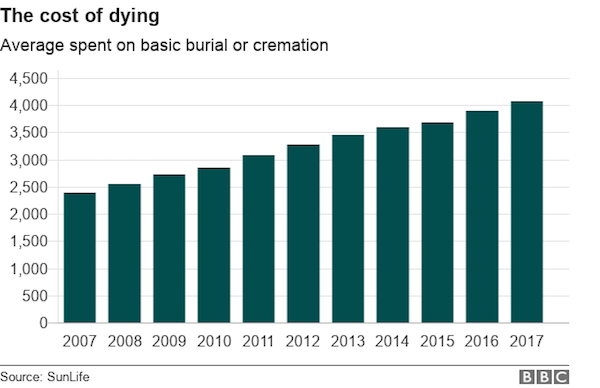

Traditional cremation is cheaper than burial, particularly as space is short, driving up the cost of grave plots. But the cost of funerals in general has been rising.

Insurance firm SunLife, which produces an annual report on the cost of funerals, says prices have risen 70% in a decade.

It put this down to lack of space and the rising cost of land as well as fuel prices and cuts to local authority budgets leading to reduced subsidies for burials and crematoria.

A survey of 45 counties, conducted by the Society of Local Council Clerks, found half of respondents’ local council run cemeteries would be full in 10 years and half of Church of England graveyards surveyed had already been formally closed to new burials.

The same problem faces Islamic burial sites.

Mohamed Omer, of the Gardens of Peace cemetery in north-east London, says the problem is compounded by a growing population and by the fact that Muslims do not cremate their dead.

The Jewish community also do not traditionally practise cremation. David Leibling, chairman of the Joint Jewish Burial Society, says all of the four largest Jewish burial organisations have acquired extra space in recent years.

However, he says it’s not such a problem for the community since synagogue members pay for their burial plots through their membership. This means the organisation can predict how many people it is going to have to bury.

“As we serve defined membership we can make accurate estimates of the space we need,” he says.

What about our digital legacy?

There are growing concerns over what will happen to people’s social media profiles after they die.

The Digital Legacy Association is working with lawyers to produce guidelines on creating a digital will, setting out people’s wishes for what happens to social media profiles – and “digital assets” such as music libraries – after death.

Three-quarters of respondents to the DLA’s annual survey say it’s important to them to be able to view a loved one’s social media profile after their death.

But almost no-one responding to the survey had used a function to nominate a digital next of kin, such as Facebook’s legacy contact or Google’s inactive account manager functions.

Both Facebook and Instagram allow family and friends to request the deceased’s account is turned into a memorial page, while Twitter says loved ones can request the deactivation of a “deceased or incapacitated person’s account”.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

I Embalm Dead Bodies For A Living — Here’s What It’s Like

By Annie Georgia Greenberg

[T]he building that houses Milward Funeral Directors in Lexington, Kentucky has been around for 193 years. It’s a three-story maze that starts with a light-soaked, stone-floored entrance hallway. The hallway is home to an awfully regal cage of tiny, yellow-breasted finches, and they greet you as you walk in through the funeral home’s front doors. Even when they’re out of sight, you can hear their occasional, lively chirps, particularly if you’re in any of the nearby pastel-hued rooms on the first floor. Say, the powder blue chapel, the pink viewing room, the green family meeting room, or the front office where office associate Elaine Kincaid has found a way to answer the ever-ringing phone with a pressing sense of compassion.

By contrast, it’s nearly pin-drop-silent in the upstairs casket showroom, where, if you were preparing to bury a loved one, you would arrive to find a selection of 30-plus casket models in every variation of wood and steel. Should you be cremating your loved one, there’s an adjoining hall where you could select an urn, each one of them unique in presentation and name — “White Orchid” for the porcelain vase and “Solitude” for the simple, gold rectangle. You could also turn loved ones’ cremated remains into jewelry, a keychain, a bench or, in the words of Miranda Robinson, Milward’s youngest mortician, “pretty much anything you want.”

Like Milward funeral home, Miranda Robinson is polished and professional. Yet, at 30-years old, she both embodies and defies the stereotypes often associated with morticians. Yes, she has a fascination with death and dying. Yes, she loves the skeletal system, owns a black cat, and displays a ouija board on her apartment’s living room table — but she’s anything but morose. In fact, her bubbly Kentucky drawl is often interrupted by a burst of up-swinging giggles, even while discussing death. She used to be a cabaret performer and closely follows RuPaul’s Drag Race. Her most-used word is “lovely” and her retro-feminine personal aesthetic matches that same description.

At around 5 feet, 4 inches tall with an obvious flair for vintage, Miranda pays almost as much attention to her own presentation as she does to those on her embalming table. Robinson clips in hair extensions that she curls every morning. Her arms, which remain covered while at work, are decorated with tattoos. One of them is of a bottle of embalming fluid.

Still, at first blush you’d never guess that Robinson works with the dead on a daily basis. And, perhaps, you’d never guess how many women her age are actively entering the field, either. Frustrated by nursing school and looking for a change, Robinson shifted gears from aiding the living to preserving the dead, and enrolled in mortuary school in Cincinnati, Ohio. In doing so she joined the ranks of young women now outnumbering men in the mortuary education system. In fact, the National Funeral Directors Association reports that, “While funeral service has traditionally been a male-domination profession…today, 60% of mortuary science students in the United States are women.”

Still, at first blush you’d never guess that Robinson works with the dead on a daily basis. And, perhaps, you’d never guess how many women her age are actively entering the field, either. Frustrated by nursing school and looking for a change, Robinson shifted gears from aiding the living to preserving the dead, and enrolled in mortuary school in Cincinnati, Ohio. In doing so she joined the ranks of young women now outnumbering men in the mortuary education system. In fact, the National Funeral Directors Association reports that, “While funeral service has traditionally been a male-domination profession…today, 60% of mortuary science students in the United States are women.”

Once a male-dominated industry, after-life and funeral care is now becoming not only a budding, female-centric space but also one ripe for disruption. And no one knows this better than Miranda. “Even in mortuary school, I was taught that [funeral service] was still a different, difficult field for women.” She explains, “Women, so I’ve heard, were expected to wear skirts and heels still, so it seemed, before I got into the funeral home, that [the] funeral service [industry] hadn’t come a long way for women… but now that I’m here, I feel like I’ve made my mark and I’m really seeing women in funeral service emerge.” They’re emerging and they’re excelling, bringing with them calm, care, and attention to detail that may have long been lacking.

While embalming, Miranda says she feels like “both an artist and a scientist,” because her work combines aspects of both. Made prevalent during the Civil War, when bodies of fallen soldiers were shipped back home for viewings and funerals, embalming is a technique used to preserve the deceased by replacing a portion of their blood with chemicals (including formaldehyde). The body is also made up to look as it did in life — lipstick and all. But, while this method may long be favored in the United States, a new wave of green burial options seeks to challenge the traditional funeral industry. In fact, for the second year running, cremation is now more popular than burials, and the National Funeral Directors Association only expects this trend to continue.

That’s because green burials, alternative and eco-friendly practices are popularizing. Some of these green practices, like home funerals and vigils, pre-date the popularization of embalming, while others like bio-urn cremation (when the body’s cremated remains are buried and grow with the seeds of a plant) or aquamation (a proposed way of breaking down a body using water rather than fire) are brand new. Whether the increased options in funeral care signify an impending end of the traditional funeral industry that Miranda is a part of is a matter that may only be answered in time. For now, what it does mean is that this freshly energized attention to death care is bringing light to a space that, despite touching every single life on Earth, has largely been kept in the shadows.

Ultimately, it is not the method of end-of or after-life care that concerns women like Miranda, but rather the instinct to talk about death in a meaningful way, early and often. Miranda loves her job because what she does helps bring peace to grieving families. She explains, “The most beautiful thing about my job, is taking the loved one into my care from a removal, especially when family is gathered, just that intensity of how much they love that person. It’s an absolute honor to be in the worst possible moment in someone’s life. To be there and for them to look at me and just me to try to at least give them some answers, to try to give them some peace in that moment.”

And while it may seem strange to light up while talking about death, it’s a conversation everyone will someday need to have, regardless of personal preference or spiritual beliefs. Miranda has this conversation every day — at work, at home, with her 1,859 instagram followers — and in doing so helps to de-stigmatize a topic that’s long been off-limits.

As a mortician, Miranda believes that viewing the body is of the utmost importance. As she puts it, “I think it’s important to see the body because you face the reality of what’s actually happened.” But, it’s the trend toward personalization, transparency and increased discussion around death and dying that continues to be a universal priority for many women working in both alternative and traditional funerals.

For Miranda, part of this conversation means addressing the details of her own funeral. And, of course, she can’t imagine anything more fitting than a traditional embalming. Ever the enigma, while her choice to embalm may be traditional, her last look will be anything but. Robinson would like a “glitter casket” with a leopard interior. Dark brown extensions will be clipped and curled, her lips will be painted in the bright red pigment Ruby Woo by Mac. Years from now, when that day comes, Miranda may very well lay on the table that she works alongside every single day at Milward Funeral Directors, in the storied embalming room that she considers sacred. Perhaps somewhere beneath her in the entry hall, the finches will be singing.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How Virtual Reality Can Help You Face Your Own Mortality

[I] was in elementary school when I first became aware of my own mortality. It was early in the morning. My mom was in the bathroom getting ready for work, and I was on her bed covered in tears, thrashing around and yelling “I don’t want to die!” over and over.

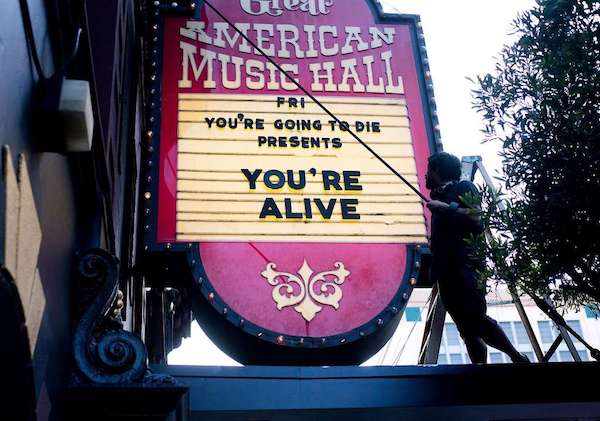

Like a lot of people, dying terrifies me, the finality of it so unthinkable that I try not to acknowledge it in my day-to-day life. So when an opportunity came to go to “Second Chance” — an interactive experience that uses theater and virtual reality to help people come to terms with their demise — I was both scared and intrigued. It was one of 175 activities that took place during Reimagine End of Life week in San Francisco, an event that consisted of panels, film screenings, and other experiences that encourage people to talk openly about death and how it affects us.

SF-based art collective Lava Saga spent three months creating “Second Chance,” transforming a two-story gallery in the city’s Mission district into an ethereal environment.

“We believe that immersion is a way to experience things, and when we have those lived and bodied experiences, we can start to answer some of those big questions around death or around life itself or any other big topic we’d like to explore,” said co-producer Scott Shigeoka in an interview.

“Second Chance” only allowed 10 people in at a time, and they all had to be strangers (one of Lava Saga’s few hard rules). It unfolded across four different rooms, with VR serving as a key piece of the production. My group entered the first space — a darkened room lit only by blue and purple lights — and found black futons on the floor, all of which had pillows and neatly folded white sheets. Next to them were Samsung Gear VR headsets and wired headphones that attendants asked us to put on after we sat on the beds.

The nearly four-minute VR sequence pulled me through a monochrome landscape filled with massive planets, intricate caverns, and pulsating tendrils that pierced the sky. An otherworldly hip-hop track from electronic artist Shigeto made the 360-degree journey feel lonely and isolating.

When the experience was over, I took the headset off and laid on the bed; another person came to pull the white sheet up to my neck. A cellist at the corner of the room began playing a peaceful but melancholic tune. I closed my eyes as our end-of-life doula (who had spoken to the group beforehand to address any concerns) read a poem from Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh.

As far as the “Second Chance” narrative was concerned, we were dead.

Simulating Death

Surprisingly, the VR music video wasn’t made for “Second Chance.” It’s a pre-existing project (known as “Hovering”) from creative studio 79 Ancestors. Lava Saga worked with VR and augmented reality curator Dream Logic to determine what kind of piece would best represent the transition between life and death.

It wasn’t easy. For awhile, they wondered whether they should even have a symbolic representation of death. After all, how do you visualize an experience that, by definition, is impossible to come back from?

“We picked [‘Hovering’] because it feels like going through a portal. And with VR in ‘Second Chance,’ we wanted it to serve that function, to be a transporting mechanism that people could go inside, be transported, and come out into a shifted reality,” said Dream Logic producer Kelly Vicars.

Though “Hovering” wasn’t created with “Second Chance” in mind, its abstract graphics made it a fitting choice for the production. During the design process, Lava Saga interviewed people who had near-death experiences, with many of them saying they were moving through a tunnel or seeing black-and-white images before being resuscitated. “Hovering” also worked well because it wasn’t scary and didn’t adhere to any specific religious beliefs.

“It was important for us to honor the diversity of cultures, traditions, and wisdom around death. … We wanted to make sure that whatever experience we used was really inclusive,” said Shigeoka.

Lava Saga and Dream Logic knew that for a lot of people, “Second Chance” would be their first opportunity to be in VR. So they tried to make the experience as seamless as possible, with attendants giving clear instructions on how to use the equipment. And Gear VR offered the least amount of friction due to its portability and ease of use (when compared to PC-based gaming headsets like Oculus Rift and HTC Vive). Participants just had to put it on and wait for “Hovering” to begin.

“My team’s goal is to use immersive technology to elevate art, to have the technology disappear,” said Vicars.

Breaking through taboo topics

After dying in VR, my group entered a series of rooms that represented a kind of liminal purgatory state. One had thin sheets of white fabric hanging from the walls and ceiling, with actors and dancers (Lava Saga refers to them as spirits) talking to each other about their previous lives.

From there, “Second Chance” starts to pull back on its mystical interpretations of an afterlife and morphs into something a little more grounded: group therapy.

In the third room, we broke into two smaller groups with trained facilitators who asked us questions about our own lives. Shigeoka said this was often an “emotionally charged” space because of the stories people would share — about their hardships, mourning for loved ones who died, or anything else they just needed to talk about. This vulnerability is why it was so vital to go through “Second Chance” with strangers instead of friends or family members.

I didn’t let my guard down completely. I couldn’t quite squash the skeptic voice in my head, which was too loud and too stubborn to go away. But I still felt comfortable in those discussions, as well as in the 1-on-1 meetings that followed in the last room, where we were randomly paired with another person from our group. That I was able to share personal details about my life at all was remarkable given that we had only met an hour before.

“Second Chance” wasn’t a perfect experience; at times, I was bored or confused about what was going on. But the core conceit — getting people to express their feelings about a sensitive topic — was sound. It reminded me that sometimes, it feels good to have someone just listen to you.

“I hope that people emerge [from ‘Second Chance’] with a new perspective and a new relationship with what it means to die. And that’s [to] live,” said Vicars.

Lava Saga and Dream Logic consider this first run as a prototype. If the show ever returns (whether in San Francisco or elsewhere), they want to keep refining it based on the feedback they receive. One day, they might make their own VR experience to replace “Hovering,” or maybe even depict that life and death transition in a totally different way.

But the idea of using theater and immersive technology to break through cultural taboos is something both teams want to keep exploring.

“It’s so important for us to open up about [death] and it’s so important for us to change the narrative around it, to make it something that should be discussed and talked about. … We need to have a conversation that goes beyond the medical world around the end of life,” said Shigeoka.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Remembering When Americans Picnicked in Cemeteries

For a time, eating and relaxing among the dead was a national pastime.

[W]ithin the iron-wrought walls of American cemeteries—beneath the shade of oak trees and tombs’ stoic penumbras—you could say many people “rest in peace.” However, not so long ago, people of the still-breathing sort gathered in graveyards to rest, and dine, in peace.

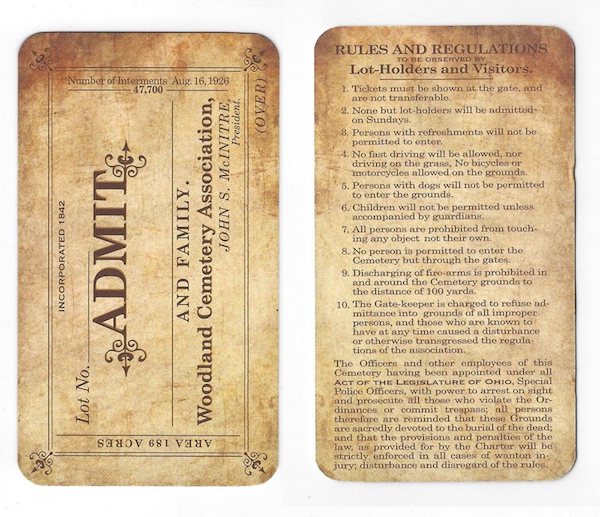

During the 19th century, and especially in its later years, snacking in cemeteries happened across the United States. It wasn’t just apple-munching alongside the winding avenues of graveyards. Since many municipalities still lacked proper recreational areas, many people had full-blown picnics in their local cemeteries. The tombstone-laden fields were the closest things, then, to modern-day public parks.

In Dayton, Ohio, for instance, Victorian-era women wielded parasols as they promenaded through mass assemblages at Woodland Cemetery, en route to luncheon on their family lots. Meanwhile, New Yorkers strolled through Saint Paul’s Churchyard in Lower Manhattan, bearing baskets filled with fruits, ginger snaps, and beef sandwiches.

One of the reasons why eating in cemeteries become a “fad,” as some reporters called it, was that epidemics were raging across the country: Yellow fever and cholera flourished, children passed away before turning 10, women died during childbirth. Death was a constant visitor for many families, and in cemeteries, people could “talk” and break bread with family and friends, both living and deceased.

“We are going to keep Thanksgivin’ with our father as [though he] was live and hearty this day last year,” explained a young man, in 1884, on why his family—mother, brothers, sisters—chose to eat in the cemetery. “We’ve brought somethin’ to eat and a spirit-lamp to boil coffee.”

The picnic-and-relaxation trend can also be understood as the flowering of the rural cemetery movement. Whereas American and European graveyards had long been austere places on Church grounds, full of memento mori and reminders not to sin, the new cemeteries were located outside of city centers and designed like gardens for relaxation and beauty. Flower motifs replaced skulls and crossbones, and the public was welcomed to enjoy the grounds.

Eating in graveyards had—and still has historical precedent. People picnic among the dead from Guatemala to parts of Greece, and similar traditions involving meals with ancestors are common throughout Asia. But plenty of Americans believed that picnics in local cemeteries were a “gruesome festivity.” This critique, notably from older generations, didn’t stop young adults from meeting up in graveyards. Instead it led to debate over proper conduct.

In some parts of the country, such as Denver, the congregations of grave picnickers grew to such numbers that police intervention was even considered. The cemeteries were becoming littered with garbage, which was seen as an affront to their sanctity. In one report about these messy gatherings, the author wrote, “thousands strew the grounds with sardine cans, beer bottles, and lunch boxes.”

Though the macabre picnics were considered “nuisances” in some communities, they did give participants a sort of admired air. One reporter lauded the fact that the picnickers looked “happy under discouraging circumstances,” and even said it was a trait “worthy of cultivation.” The fad of casual en plein air dining among the crypts would soon come to an end, though.

Cemetery picnics remained peripheral cultural staples in the early 20th century; however, they began to wane in popularity by the 1920s. Medical advancements made early deaths less common, and public parks were sprouting across the nation. It was a recipe for less interesting dining venues.

Today, more than 100 years since Americans debated the trend, you’d be hard-pressed to find many cemeteries—especially those in big cities—with policies or available land that allow for picnics. Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, for example, has a no picnic rule.

But the fad isn’t entirely dead in the United States. The country’s immigrant population includes families carrying on traditions that call for meals with departed loved ones, and cemeteries will hold occasional public events in the spirit of this era. There are still scattered graveyards where you can picnic among tombstones, too, particularly if you know someone with a sizable family lot. In those cases, all you need is a picnic basket filled with treats, and you and your undaunted party can partake in an old American tradition. Just remember to clean up after yourselves. The penalties for doing otherwise may be grave.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Glasnevin Cemetery Tour

Shane MacThomáis of Glasnevim Museum gives us a tour around the world famous Glasnevin Cemetery and Museum, Dublin.

Culture clash: Asian Americans balance Christianity and culture in rituals honoring their ancestors

by Ruth Tam

[W]hen my great-grandmother died, I didn’t know how to pay my respects.

I was 9 years old, and had seen other Chinese people bow at funerals and gravesites before. One, two, three times.

But, my parents told me as we approached her coffin, we don’t do that.

Nor would we participate in any of the traditional Chinese ancestral rites of burning incense and paper money, or leaving food for her as an offering in the afterlife.

Like 42 percent of Asian Americans, my parents are Christian. And for believers like them, Chinese ancestor veneration inappropriately elevates the dead. The bowing, in particular, is akin to “idol worship,” a direct contradiction of their faith. The burning of money and offering of food are supposed to be gifts to the dead in the afterlife. But to Christians, death isn’t the door to a spirit world where material things are needed, but the beginning of life in heaven.

This year, my father told me we would visit my grandparents’ graves around Qingming Jie, the annual Chinese Tombsweeping festival, which this year fell on April 5. Joining millions of Chinese families celebrating the spring holiday to honor the dead, we planned to make the pilgrimage to our family burial grounds. We would clean my grandparents’ gravesites and reflect on their lives. But we wouldn’t bow, burn incense and paper money or leave food.

My parents left Hong Kong 50 years ago. For the first time I wondered: Are they now more Christian than Chinese? Had Christianity become our primary culture here in America?

My family isn’t the only one grappling with these questions.

Before Chinese American Jordan Kwan and his family converted to Christianity, they would bring oranges and a dim sum dish to a cemetery in Oakland, Calif., and participate in all the traditional ancestor veneration rituals.

He remembers them changing their routine when he was in the sixth grade.

“You don’t have to bow,” his newly Christian parents told him.

How did Chinese families like ours come to feel that our culture was incompatible with Christianity?

Sze-Kar Wan, professor of New Testament at Southern Methodist University, says it stems from an error in translation.

In ancient Chinese, the word for ancestor veneration, “jizu,” was defined as the act of sacrifice to the deities. In a modern context, Wan says it simply describes the commemoration of the dead.

Historically, practicing ancestral rites is deeply knit into Chinese culture — particularly because it embodies filial piety, the Confucian virtue of respect for one’s elders. Although it plays a central role in the Tombsweeping festival, it is traditionally observed during all major holidays.

Europeans initially believed China to be an enlightened society without Christianity, but that changed by the mid-18th to 19th century. Western missionaries viewed some aspects of Chinese culture as an obstacle to their religion and did everything to counter them, Wan says.

This included translating “jizu” to “ancestor worship.” In doing so, missionaries played a part in defining Chinese tradition to the English-speaking world and pitting it against a Christian God.

“Do not worship any other god,” the Bible reads. “The Lord … is a jealous God.”

Chinese American Serena Cerezo Poon remembers traveling to Hong Kong from California for her grandmother’s funeral in 2003. Her cousin played Christian worship music on his guitar, drowning out the Buddhist monks chanting at nearby services. Her mother placed a sign next to her grandmother’s coffin that read, “No Bowing.”

“I was surprised she didn’t physically stand next to the coffin and stop people mid-bow,” Cerezo Poon said.

Before her family’s trip, Cerezo Poon had researched the influence missionaries had in China as a college student.

“Christian missionaries said it was evil,” she says of ancestor veneration. “But when it’s such a big part of the culture, it was like them saying ‘You can’t be Chinese anymore, it’s evil.’ ”

After Catholic and Protestant missionaries established more churches in China by the 19th century, many new converts were ostracized for their faith and their rejection of Chinese traditions such as ancestor veneration. In extreme examples, such as the 1899 Boxer rebellion, they were persecuted and killed.

Despite political challenges, Christianity in China has endured into the 21st century. In 2010, the Pew Research Center estimated the country’s Christian population to be over 67 million, 5 percent of the national population, and other scholars say current numbers could be nearly twice that.

Today, the influence of Western missionaries is still evident in Chinese Christians whose families like mine, Kwan’s and Cerezo Poon’s immigrated to the United States.

But the hard-line approach against ancestor veneration could be fading in a world where cultures are becoming increasingly hybrid.

“I think one could look at ancestor veneration as a continuation of memory,” Wan says. Our dead “do not have independent status or power from God, but we can acknowledge that they are now in the repose of God and that it is important to remember them. That could really be worked into the modern Christian worldview.”

Other Asian Americans have found a compromise between their mother culture and adopted religion.

Desiree Nguyen is a Vietnamese American Catholic whose ancestor veneration rituals closely resemble Chinese traditions.

“When I found out that some Vietnamese gave up ancestor worship after converting to Catholicism, I thought it was a real shame,” Nguyen says. “Ancestor veneration, or respecting elders, is really a crucial part of our culture.”

The Vatican has recognized this and officially allowed Vietnamese Catholics to practice ancestral veneration in 1968.

On major holidays, including Lunar New Year and Christmas, Nguyen’s family gathers around an altar for her ancestors. They light incense, bow three times, say Christian prayers and sometimes pray the rosary.

“I always thought white Christianity’s approach to death and spirits was pitifully narrow,” says Nguyen of the early condemnation of ancestor veneration. “Christianity is deeply layered and complex, and that’s a beautiful thing.”

Regardless of religion, it can be difficult for immigrants to uphold and pass on rituals from their home country.

When my family paid our respects at my grandparents’ gravesites this spring, I couldn’t recall the last time we visited.

But we poured water over their headstones, swept wet twigs from the crevices and scrubbed the surface clean. We repurposed palm crosses from Palm Sunday, sticking them in the moist ground behind the memorials. Borrowing from Jewish tradition, we placed a stone on top of their graves, leaving notes for our deceased beneath.

We came to the cemetery to honor our ancestors. And when we remembered the dead, we reflected ourselves — a mix of culture and faith in a country where we now celebrate both.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The ‘Outside Lands of Death’ is coming to SF

In just a few weeks, almost every corner of San Francisco will have death at its heel. The topic both universally experienced — and stigmatized — will be up for discussion in a variety of forms around the city.

[R]eimagine, a nonprofit sprouted from IDEO, is putting on the Bay Area’s first so-called “death event series.” More than 100 events, each hosted by an individual organizer, will be offered to the public beginning on April 16 up until April 22. The nonprofit expects 7,000 people who are still alive to attend.

The events will cover all the ways death alters our lives — from the pragmatic (working with physicians to get Advanced Directives straightened out) to the artistic (drinking from ceramic cups made using the ashes of 200 anonymous people) to the literary (the science around the use of psychedelics and death with Dr. Richard Miller).

There will be highly-mortal film screenings (including a talk with Lee Unkrich, director of “Coco”), comedy shows (Mortified: Let’s Talk about Death, Baby), and psychodrama taken to the next level (Dead for a Day: Attend your own funeral to “altar” your life). Actress Francis McDormand will also be at the Castro Theater on April 19. for a “Theatrical Exploration of Death, Dying and Suffering.”

Aside from the arts, the events will draw on the subjects of healthcare, design, and spirituality. Brad Wolfe, Executive Director and Founder of Reimagine, wanted the event series programming to be valuable for — and reflective of — as many people as possible.

The death-positive movement — which is broad enough to contain anything from Caitlin Doughty’s Ask a Mortician YouTube series to amateur banjo sessions about the beautiful uncertainty of our mortality — has valiantly taken on the challenge of eliminating a major stigma. But in some cases, it has also been critiqued for being white-centered, and glamorizing a topic that has never, and will never, for many communities of color, feel whimsical.

That concern is exactly what Reimagine’s founders kept in mind, in the pursuit of designing an event series that would be inclusive of people outside death talk’s main demographic: middle-class white people who have the luxury of mortal musings. One such event will be hosted by Dr. Jessica Zitter, a Critical and Palliative Care Specialist at Oakland’s Highland Hospital in conversation with Pastor Corey Kennard at Glide Memorial Church.

The talk will explore the wealth of research behind racial inequities in healthcare at the end of life, and discuss the divide between dying African-American patients and a healthcare system that falls short of providing the right kind of support.

Zitter wrote an insider’s perspective on the problems with the way the dying are treated in our current medical culture in her 2016 book, “Extreme Measures: Finding a Better Path to the End of Life.” The book has been lauded by the likes of BJ Miller, a UCSF doctor and triple amputee and Lucy Kalanithi, a Stanford doctor and the widow of a Stanford doctor whose memoir on dying from cancer was released posthumously.

Her conversation with Kennard will also touch on her anecdotal experience with an aspect of healthcare that’s untaught in the medical world: finding a common language with patients who are dying that’s beyond the withdrawn and overly sterile protocol.

In her practice, she said, she underestimated the role that things like prayer, miracles, and hope mean to her African-American patients, who, “come into a hospital in their darkest hours and are met with language and concepts that feel like in a way that they’re robbing of their humanity, robbing of their opportunities for being whole.”

It was only through the years she’d been working with Betty Clark, an African-American chaplain, that she began to notice the vital components of healthcare support for her patients of color that she’d overlooked.

“There are many, many areas I had wished to delegate to others that I felt were not part of my job that are absolutely part of my job.” Zitter said.”But I really have to say that it’s really powerful to [pray with my patients]. It’s not necessarily about God, but it’s about connecting to them, and supporting them.”

The second in her series of discussion with Kennard will take place at the Oakland Museum of California on April 17., and cover the intersections of faith and medicine at the end of life.

A full event schedule is available on Reimagine’s website. Some highlights are in the slideshow above.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!