By Charlotte Cowles

In 2012, Alua Arthur quit her legal career to become a death doula. The problem was that she had no idea such a job existed. “All I knew was that there had to be a better way to give support during one of the most lonely and isolating experiences a person can go through,” she says. Now 42, she is a leader in the field of death work and has guided thousands of people and their loved ones through the end-of-life process. She has also trained hundreds of other death doulas through her company, Going With Grace, and is on the board of directors at the National End-of-Life Doula Alliance (NEDA)

This year, as COVID has forced so many Americans to cope with sudden loss and their own mortality, Arthur has been inundated with new clients and students as well as larger questions about how to handle constant grief. She lives in Los Angeles. Here’s how she gets it done.

On her morning routine:

I usually get up around 8:30 or 9:00 a.m. I’m a night owl, and it helps me in my work because people tend to die between 2:00 and 5:00 a.m. I’m not sure why; there are a lot of different theories about it. But I’m most awake and alert at that time. The witching hours. I love to burn my incense at 4:00 a.m. and greet the crows.

Most mornings I meditate right after I get up. After I meditate, I fill up my gallon jug of water and exercise. I need to sweat and move. I love anything where the instructor is like, “Faster! Go! Only ten more seconds!” Since we can’t do group fitness in person right now, I have to re-create it in my house. It doesn’t work quite the same, because I will stop and eat snacks in the middle of a video. But I’m trying. Exercise and meditation are the things that keep me sane and grounded. They’re the baseline.

On being drawn to end-of-life care:

Being around death has made me more honest. I see that what we don’t say chokes us as we die. People always think they have more time, and when they realize that they don’t, they have regrets about things they haven’t done. I try to do what I feel like doing right now. And if that means eating white-cheddar Cheetos for breakfast, I will. Which is what I did this morning. I won’t always be able to taste delicious things, so let me do it now.

On managing her clients:

I don’t take on more than one client at a time who is imminently dying, because I want to be on call for them. Whatever they need, I will do. When a client with just a couple of weeks or months left first comes to me, we’ll go through the long list of items to consider in death and dying, and then we’ll create a plan. That usually happens over the phone. Then I go to visit, put my hands on them, really see what their physical condition is, and see what kind of support they have.

I continue to visit every week or so until their condition starts deteriorating fast, and then I’m there more often. I might be there when they die, and if I’m not, I’ll come sit with their family or caregivers afterward until the funeral home comes. I may also help wrap up practical affairs — possessions, accounts, life insurance, documents. It’s exhausting for a family to have to think about that when they’re also grieving, and I’m equipped to help. I’ll sit on hold with insurance companies, make funeral arrangements, all that stuff.

Beyond those who are imminently dying, I often have several clients who need end-of-life planning consultations. I can take on a couple of those at a time. That could be someone who has just gone on hospice and it doesn’t look that bad yet, or someone who just received a diagnosis and wants to prepare.

On winding down after an intense day:

I’ll drink wine and hang out with a lover. I’ll go out dancing until 5:00 a.m. Sometimes I just want to shut the brain off after a long day, and the best way to do that is by spending time with friends and people who tickle me. But it’s also good to spend a lot of time alone, which is the default these days. I like silence.

On becoming a death doula:

I spent the bulk of my career in legal services in L.A., working with victims of domestic violence. Then there were some big budget cuts, and I wound up getting stuck doing paperwork in the courthouse basement. I was already depressed and burnt out, but it blossomed into an actual clinical depression. So I took a leave of absence and traveled to Cuba. While I was there, I met a German woman who had uterine cancer and was doing a bucket list trip. We talked a lot about her illness, and her death. She hadn’t been able to discuss a lot of those things before, because nobody in her life was making space for her to talk about her death. Instead, they’d say, “Oh, don’t worry. You’re going to get better.” I came back from that trip thinking I wanted to be a therapist who worked with people who were dying.

I applied to schools to become a therapist, but in the meantime, my brother-in-law got very sick. So I packed up and spent two months in New York with him. That experience gave me a lot of clarity on all the things we could be doing better in the end-of-life processes. It was so isolating and I couldn’t understand why. Everybody dies — so why does it feel so lonely? After that, I did a death doula program in Los Angeles, called Sacred Crossings, and then I founded my company, Going With Grace.

On leaving her law career (and a steady paycheck):

It wasn’t a hard decision to leave my job as an attorney. The challenging part had more to do with identity and what achievement means. I was born in Ghana, and we’re all raised to be doctors and lawyers and engineers. So I was going against societal expectation and parental expectation. It was also tough to be broke for a long time. My student loans were in forbearance. I spent a lot of nights lying on my mom’s couch wondering how I was going to make things work. If my friends were going out, they’d have to pay for me or else I couldn’t join them. To support myself while I was starting my business, I worked part-time jobs at a hospice and a funeral home.

Eventually, I started hosting small workshops about end-of-life planning. I charged $44 dollars for people to come together and learn how to fill out the necessary documents. Now I have my own doula training programs. I have about 100 students at the moment, all online.

On charging for her services:

I have to navigate the financial conversations with a lot of directness. Part of the challenge is that our society doesn’t see the financial value of having somebody be kind and supportive. Being able to hold so much compassionate space when somebody’s dying — that is a skill. It needs to be compensated highly.

On living with grief:

I’m constantly grieving with and for my clients and their family members, all the time. There’s no fixing it. I have to be present with my feelings and let them wash over me, in whatever expression they take. If I try to shut off that part of myself, it becomes much harder to function in everyday life. Grief doesn’t always look like crying. Sometimes it looks like anger, promiscuity, or eating everything under the sun. Like all things, it’s temporary.

On how COVID has changed her work:

We have to rely much more heavily on technology and remote communication. There’s also a lot more interest in the death doula training program. Death is on a lot of people’s minds, and I’ve seen a lot more people starting to do their end-of-life planning — mostly healthy people in their 40s with young kids. A lot of people have seen younger people die suddenly, and it’s changed their perspective.

On her own end-of-life plan:

I would love to be outside or by windows. I want to watch the sunset for the last time, and I want to have the people I love around, quietly talking, so that I know they’ve got each other after I leave. I want to have a soft blanket and a pair of socks because I hate it when my feet are cold. I want to smell nag champa incense and amber. And I want to hear the sound of running water, like a creek. I’d love to enjoy all those senses for the last time. And when I die, I want everybody to clap. Like, “Good job. You did it.”

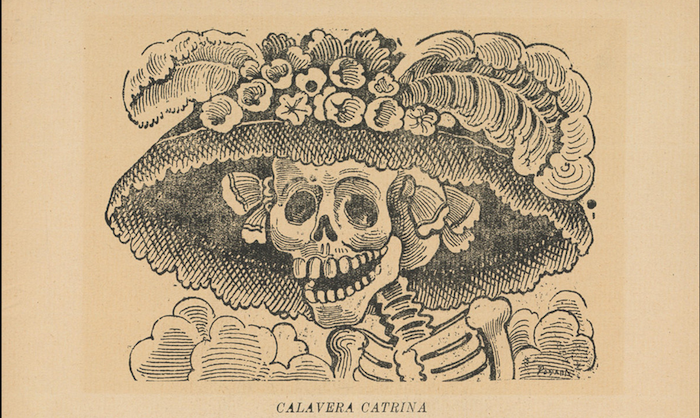

I want my funeral to be outside, and I want all my jewelry to be laid out. As guests come in, they grab a piece and put it on. I want my body to be wrapped in an orange and pink raw silk shroud. They’ll play Stevie Wonder — “I’ll be loving you always” — and everyone will eat a lot of food and drink whiskey and mezcal and red wine. There will be colorful Gerber daisies everywhere, and they’ll take me away as the sun goes down. And when they put my body in the car, the bass will drop on the music, and there will be pyrotechnics of some sort. I hope my guests have a grand old time and dance and cry and hug each other. And then I want them to leave wearing my jewelry.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!