By Matt Pickles

Maths, science, history and death?

This could be a school timetable in a state in Australia, if a proposal by the Australian Medical Association Queensland is accepted.

They want young people to be made more familiar with talking about the end of life.

Doctors say that improvements in medicine and an ageing population mean that there are rising numbers of families facing difficult questions about their elderly relatives and how they will face their last days.

But too often young people in the West are not prepared for talking about such difficult decisions. There is a taboo around the subject and most deaths happen out of sight in hospitals.

Pupils might have reservations about lessons in death education.

Dying days

But the Australian doctors argue that if the law and ethics around palliative care and euthanasia were taught in classrooms, it would make such issues less “traumatic” and help people to make better informed decisions.

Queensland GP Dr Richard Kidd says young people can find themselves having to make decisions about how relatives are treated in their dying days.

“I have seen people as young as 21 being thrust into the role of power of attorney,” he says.

Their lack of knowledge makes it a steep learning curve in “how to do things in a way that is in the best interests of their loved ones and complies with the law”, he says.

He says the taboo around death means that families usually avoid discussing until it is too late. Most people do not know how their relatives want to be treated if the worst happens.

“So we need to start preparing young people and getting them to have tough conversations with their loved ones,” he says.

“Death lessons” could include the legal aspects of what mental and physical capacity means, how to draw up a will and an advanced care plan, and the biological processes of dying and death.

These topics could be incorporated into existing subjects, such as biology, medicine, ethics and law.

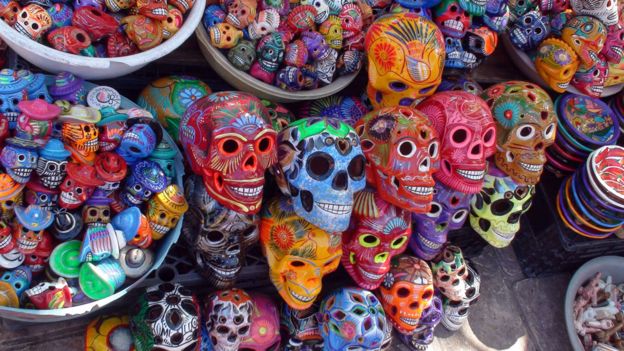

Dr Kidd says education around death would help countries like Australia, the US and the UK follow the example of Mexico, where death is an important part of the culture and even celebrated in the Day of the Dead festival.

He gives the example of Ireland, where he says wakes held after a death can be “joyous occasions”.

Introducing a culture of openly discussing death could even change where we die, according to Dr Kidd.

The vast majority of Australians die in hospital, even though many people say they would rather die at home with their family around them.

“Only 15% of people die at home but in the case of many more people, they could have died at home rather than hospital if there had only been a bit of preparation,” says Dr Kidd.

Matter of life and death

A hundred years ago it was very normal for people to die at home. but modern medical technology allows life to be prolonged in hospital, even though the patient might not have great quality of life.

“People may decide that at a certain point they want to be able to die at home in comfort rather than being kept in hospital,” he says.

The proposal for lessons in death has now been put to the Queensland education authorities and Dr Kidd hopes the message reaches other parts of the world.

“Our main aim is to get young people to start having those conversations with their parents and grandparents to learn more about how they want to die so that they know the answer when they need that information in the future,” he says.

“It should be seen as a positive and proactive thing – information and knowledge can be really empowering to people.”

So perhaps this is something to bring up over your next family Sunday lunch.

It might not be an easy conversation but it could be a matter of life and death.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!