Ways to Help Yourself and Your Surviving Parent

A grief-support expert shares a letter she wrote to a grieving friend

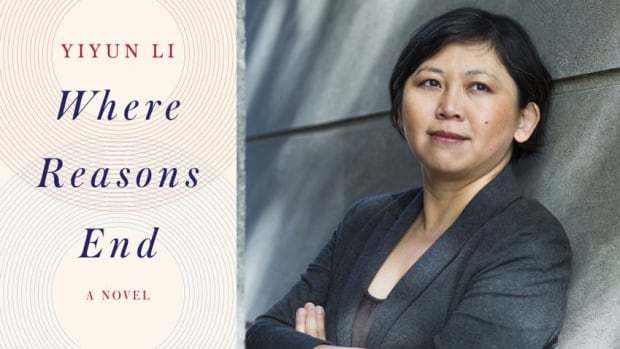

By Amy Florian

Not too long ago, a dear friend’s dad suffered a major heart attack and died. At the funeral, there was little time for more than a brief exchange of words.

But, given my background in grieving support and education, I wanted to offer some advice to help her and her mom through the grieving process. So, that evening I wrote her a letter. I’m sharing it here because I believe it can be of help to anyone who has recently lost a parent and wants to help their surviving parent through the grief. Here is what I wrote:

Dear Katie,

The way-too-soon and totally unexpected death of your dad has hit you hard. It was clear at the services that your family is reeling, trying to comprehend what happened to you, to understand the enormity of this loss, and to figure out what to do now.

Leave behind the well-meaning compulsion to cheer each other up or keep looking on the bright side.

I’m glad I was able to attend the services to celebrate his life and mourn his death together, and I also know your grief has only begun.

I remember after my husband’s death, a few of the letters that people wrote were extremely helpful — not the ones telling me the writer’s own story of grief, as if I was supposed to experience the same thing and handle it in the same way, but those that contained hard-won wisdom from grieving people.

In that vein, I offer you some input that may be helpful to you and your mom, gleaned from my many years of providing grief education, facilitating grief support groups and counseling grieving people.

If any of this does not apply in your case or is not helpful, then set it aside. Everyone grieves uniquely and you don’t have to meet my (or anyone else’s) expectations.

Grief hurts. We don’t want to face the pain, the loneliness and the void that will never be filled in the same way again. But if we don’t, we won’t heal.

Grief that is suppressed, denied or ignored does not go away. It stays there, it festers and it will find a way to come back out and bite you in physical, psychological, spiritual and emotional ways.

But it also helps to try to set the grief aside sometimes, as if in a box on the shelf, and let yourself smile or enjoy life for a bit. Those times will sustain you.

Don’t be afraid of bringing up your dad, saying his name and telling the stories. Will it cause tears? Yes, sometimes, but that’s not because you brought it up. The tears are there anyway. It is healing to allow them to spill out, whether you are alone or especially when you share those tears with someone else who also loved him, whether it’s your mom or supportive friends who will let you cry with them.

Did you know that there are physiological chemicals in tears that relieve stress? Tears are our natural stress-relief mechanism when we are sad — that’s why we call it “having a good cry.” So, when you cry, you help yourself heal.

One final thing about tears. People often say they can’t start crying because if they do, they will never be able to stop. Do you know that has not happened in the history of humankind? No one has ever not been able to stop crying. Allow the healing to happen, facilitated by allowing tears when they are there.

As you support your mom, remember your job is not to “fix it” or to make her feel better. Your job is to be her companion, to be there for her whatever she is feeling.

Leave behind the well-meaning compulsion to cheer each other up or keep looking on the bright side. Instead, just keep checking in. Ask what kind of a day it is today — feeling up, down or all over the place?

Talk about when you miss your dad the most. Share your stories about things people say that are helpful, and the well-intentioned things people say that are not! Share what you each wish people knew about what you’re going through. Keep the lines of communication as open as possible, so you can pour your experience out to each other and gain comfort.

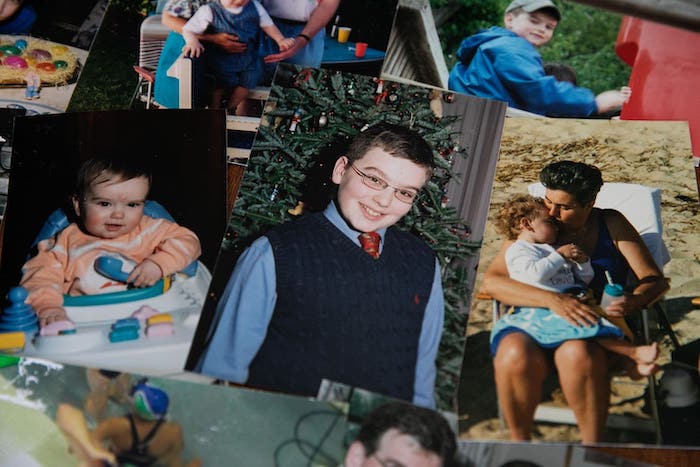

Keep in mind that grief takes a very long time. Expect to hit sad periods of time again weeks or months after the death. This is especially true when those “marker days” hit: his birthday (and yours), the wedding anniversary, Father’s Day, the holidays, the monthly and yearly anniversaries of his death.

You will be sad over and over again. You will be happy over and over again, and eventually the happiness will predominate. But expect a roller coaster of emotions — some hours and days will be better, and some will feel like disasters. Hang in there. As long as you continue doing the hard work of grief, you are healing, you will heal and you will get there.

Another word about those “marker days.” Your dad’s absence will be huge, and yet the tendency of most people around you will be to talk about anyone and everything except your dad.

The intention is good — they want to keep you from feeling sad. Yet, these are the times it is most important to say his name, share the memories and keep his legacy alive.

His life and the lessons he taught you are with you forever. His love is with you forever. You are a different person because of him, and no one can ever take that away from you. Keep his name, his stories and your memories alive, even as you let go of all the things that can no longer be.

These are just a few things that I hope can get you on the path to healing. My most fervent hope is that your family may heal, carrying memories and stories of your dad’s life with you even as you move into a future that will be different than you had planned.

I will check in regularly, just to see what’s happening and how you’re doing. I am here for you for the long haul, no matter what.

I hold you and your mom close to my heart. In these crazy, turbulent days, I wish you moments of peace, an occasional smile and continued healing.

Love and hugs,

Amy

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!