Dr Cathy Welch

The argument about who can or should be responsible for confirmation of death has escalated and evolved over the past few years, alongside changing opinions and legislation regarding CPR and end of life care planning, etc.

But the rise of the Covid-19 crisis has taken the issue to another level. And so, the argument rages on about who owns the rights to use the title ‘Confirmation of Death’©️.

Should death be a medical diagnosis? Are nurses capable of diagnosing death?

And now arise the questions ‘does it have to be a healthcare professional?’; ‘does the healthcare professional have to be there in person?’; and ‘can undertakers confirm death?’

The law has not significantly changed – it still remains that any competent person can confirm death. It‘s only by convention that ‘person’ has been historically replaced (to varying extent by postcode lottery) with ‘healthcare professional’.

Unfortunately, Pulse’s article ‘DHSC says GPs can provide ‘remote clinical support’ for death verification’ earlier this year continues to use language that perpetuates the unnecessary dogma that this is ultimately a medical role.

Within Dr David Church’s relatively recent blog ‘The stormy night that shaped my views on death verification’, and the following responses, all I see are attempts to justify the status quo based purely on anecdote and modern medical cultural convention. We all want to believe that the days of healthcare policy being based on anecdote are gone, but in reality this is all based on personal bias, hearsay, and myth.

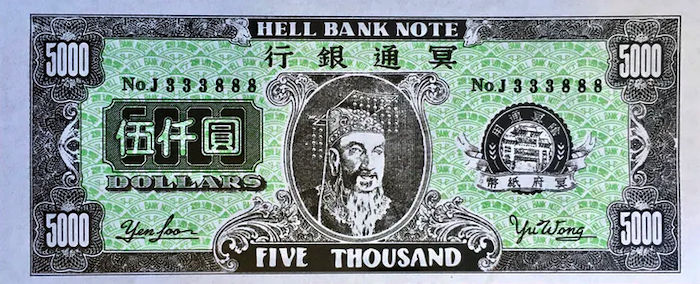

Let’s stop trying to insist that ‘confirmation of death’ is some kind of healthcare copyright issue

So, in the discussions and comments, out come the historical tales of live burials – should we then advocate having a bell system installed in all graves again, as in the 19th Century? And the hypothermic resurrections from the dead – should then every cold body be warmed up, as in the Resus Council hypothermia guidelines (not dead until warm and dead)? Good luck convincing all the hospitals and mortuaries to warm all bodies to normal temperatures before confirming death – they’d be stinking fly pits!

Yes, errors do happen, but extremely rarely. Healthcare-only verification of death is a modern phenomena, driven by persisting attempts to use medical ‘knowledge’ to run away from the inevitable. It’s time to grow up and stop using rare ‘errors’ in verification to cling to current imperfect, unsustainable and inhumane dogmatic ‘rules’ governing ownership of death. How will western society finally grow some cultural wisdom and accept that death is a normal part of life? That death is not failure, not an error, but is an absolute fact of existence, with a 100% lifetime prevalence?

It won’t, as long as the medical/healthcare world continues to grasp at and peddle the concept that death is a medical diagnosis, and can only be confirmed by someone with a five-year degree and however-many years’ apprenticeship. As long as the Grand Guild of Medical Magicians continues to promote the myths that life and death are under our mysterious control, people will continue to live in the shadows of mortal fear, beholden to us to rescue them, and so keep expressing the very same unrealistic expectations that GP mages complain about every day.

My opinion on confirmation of death… the bodies of those who have died will all be dealt with by either an undertaker (mostly), or a pathology morgue. Undertakers are the experts in management of death – handling, dressing, caring for and disposing of the bodies of the deceased. Surely then, they are best placed to be trained in recognition and confirmation of death in the community, as a standard part of their normal procedures?

Death is not a medical ‘condition’ or ‘diagnosis’ to warrant its control by medical/healthcare workers, any more than birth or taxes. Hand back normality to the people. Then, we may find other unrealistic expectations ‘imposed’ on us from our patients start to dissolve away too, because we‘ve been the ones clinging to their ‘need’ for us all the time.

Let’s stop trying to insist that ‘confirmation of death’ is some kind of healthcare copyright issue.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!