— to Deceased People Nationwide

By Sophie Hirsh

Human composting, an eco-friendly alternative to traditional burial, has already been made legal in Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington. Plus, states including California, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York have introduced legislation to legalize the process. So as the carbon neutral burial process grows in legality across the nation, more and more human composting facilities and funeral homes are springing up.

Thinking about your end of life can be scary — and made even scarier when considering the high environmental impacts of traditional death practices such as burial and cremation.

So if you are interested in learning more about human composting and your body returning to the earth when you leave this planet, keep reading for a look into a few of the innovative funeral homes leading the way in human composting, aka natural organic reduction.

Recompose is leading the way for human composting in the U.S..

Source: SABEL ROIZEN Recompose’s human composting vessel.

Recompose, which is based in Kent, Wash., is a full-service funeral home that works directly with clients and families for empathetic end-of-life processes. After a client passes away, for 30 days, the Recompose team regularly mixes the body with soil, alfalfa, woodchips, and straw in a Recompose vessel.

Once the body has fully turned into soil, they remove any items that did not break down, such as dental fillings or metal pins and screws, and recycle them; the soil is then moved to a bin for several more weeks to cure and dry. Recompose will then offer some topsoil to the person’s loved ones; otherwise, it will be donated to a conservation partner.

Recompose’s full-service burial (including local transportation of the body, the entire natural organic reduction process, death certificate filing, an online obituary, and more) costs $7,000. The company’s services are open to people anywhere; but you’ll be responsible for paying to transport the body to Washington.

Not only was Recompose the first licensed human composting funeral home to open in the U.S., but Recompose and its founder Katrina Spade actually inspired a Washington bill to legalize the process in the state back in 2019. Additionally, the Recompose team is also helping pave the way for other states to legalize human composting, which you can learn more about on the public policy section of Recompose’s website. The company is also planning to open a second location by the end of 2022, in Colorado.

Return Home offers human composting in Washington and nationwide.

View this post on Instagram

Return Home, which opened in 2021, offers “inclusive, gentle, transparent death care” via its Terramation human composting process. The company’s facility is based in Auburn, Wash., but offers its services to people across all 50 states and Canada.

At Return Home, deceased bodies are placed in a vessel. For 30 days, oxygen is flowed through to stimulate microbes in the body, which turns it to soil; then for the following 30 days, the soil rests and stabilizes. During these 60 days, visitors can come visit their deceased loved one in their vessel at Return Home’s facility turning business hours. At the end of the process, the deceased’s family can take the soil, or opt to have it scattered in nature.

Return Home’s full-service process costs $4,950. The company allows people to plan ahead to arrange their eco-friendly burials; it also offers services to those with an immediate need, and keeps its phone lines open 24/7 for this purpose.

Return Home is passionate about legalizing human composting more widely, and the company created the #IdRatherBeCompost campaign to help lead this movement. You can find a letter-writing template on Return Home’s website, which you can use to encourage your elected officials to support legalizing natural organic reduction in your state.

Earth offers natural organic reduction in Washington and Oregon.

“Funeral brand” Earth describes offers burial via a 45-day process called soil transformation. Earth uses its proprietary vessel technology; a balance of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and water; materials like mulch, wildflowers, and woodchips; and ideal moisture and temperature levels to create the optimized conditions for microbes and bacteria to break down the body, much like it would in nature.

At the end of the process, the deceased’s family choose to plant or scatter some of the resulting soil; the remaining soil is used for land restoration projects on the company’s conservation site in Washington’s Olympic Peninsula.

Earth has two facilities, located in Portland, Ore. and Auburn, Wash., both of which are powered by renewable electric energy. Currently, the company is only offering its services to those based in the Pacific Northwest (more details can be found here). Even though transporting dead bodies is legal, Earth believes “doing so undermines one of the greatest advantages of soil transformation, which is that the process is carbon neutral.”

Earth’s soil transformation package — which includes funeral services, all paperwork, and more — typically costs between $5,000 and $6,000.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

In life, my sister taught me how to love. In death, she made me want to fix the funeral industry

After Allison’s funeral, Jackie Bailey enrolled in a master of theology. Now she’s an interfaith minister, deathwalker, celebrant and funeral director – and the author of a new book she wrote for her sister

By Jackie Bailey

I hold his lower leg up so his daughter can gently wash underneath his knee. Then she does the same for me. We kneel on each side of her father’s body, which we brought home from the hospital where he died last night.

“You do his face,” I say and move back to the base of the bed where I wring out my cloth in the warm water. My colleague arrives with a cooling plate. His daughter and I finish washing him and drying him, then we dress him in his best suit and place him on a sheet over the plate. The plate means that his daughter can keep him at home until it’s time for the cremation.

We draw another sheet up to his chest. I light candles and place them at each corner of the bed as his daughter scatters rose petals around him. Tomorrow we will place him in a wicker casket. We will surround him with garlands and greenery and carry him out to the hearse. His daughter will accompany him to the crematorium where she will bear witness as her father’s body is placed in the fire.

It’s seven years since my sister Allison died. She lived for most of her life with various degenerative conditions as the result of brain cancer. My family gave her a beautiful send-off. Her adult nieces and nephews, whom she had babysat when little, brought her special mementoes, prepared a slideshow, decorated the casket.

I brought felt-tipped pens so we could write final messages on her eco-coffin. My daughter, then three years old, drew “potato people” on the side of the casket to keep Aunty Allison company on her final journey. Friends and family said prayers. I, my brother and our eldest sister gave the eulogy.

After Allison’s funeral I took a break from writing the manuscript which would eventually become my new novel The Eulogy. I needed some time away from our story. But instead of a holiday, I found myself enrolled in a masters of theology. Two years later I was an ordained interfaith minister, a trained deathwalker, a celebrant and independent funeral director.

Interfaith ministers offer pastoral care outside of religious institutions, creating spiritual services for the nonreligious. Many of my peers became chaplains in hospitals and prisons, social workers, university counsellors. But for me it was always about death. I wanted to give others what my sister’s funeral had given me: a clean wound, ready for healing.

But not everything about my sister’s funeral was perfect. I had chafed under the transactional gaze of the funeral directors. The inflated price of the eco-coffin outraged me, along with the attempts to upsell my grieving mother on urns, nameplates, casket decorations.

I later found out that the funeral company we had hired was not a local family firm as I had thought, but was actually owned by the multinational company InvoCare, which controls more than a third of the funeral market in Australia.

State and federal governments have held a number of inquiries, attempting to make the funeral industry more transparent, recognising that consumers are particularly vulnerable at these times of their lives.

But I want more than competition in the funeral industry. I want there to be no “industry”. When my sister died, I was not a consumer; I was a grieving puddle of emotions. I wanted a human I could trust to walk with me.

My book takes the form of a fictional guide for how to write a eulogy, as the protagonist prepares for her own sister’s funeral.

In reality I have never been able to find a good guide to eulogy writing. They all seem to assume you are telling the story of a prosperous businessman who has lived to a ripe old age. But what about people like my sister Allison, who had no career, no children, no value in this calculus, even though she was the defining person in my life, the person who taught me how to love?

In the end I wrote an entire book to say goodbye to my sister. But if you only have a time slot in a funeral service, here is my advice: it does not have to be perfect. It does not have to be long. And it is completely OK to cry, laugh or do both simultaneously.

In 2017 I conducted my first funeral. It was for a nonprofit funeral provider in my local area, a charity that believes someone’s death should not be an opportunity to take a company public.

I was nervous before the service began, but once it started, the anxiety just floated away. It was so clear that this event was not about me. I was there to give permission to people to feel whatever might arise: sadness, relief, despair, gladness. I was there to walk with them.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The psychedelic drug that could explain our belief in life after death

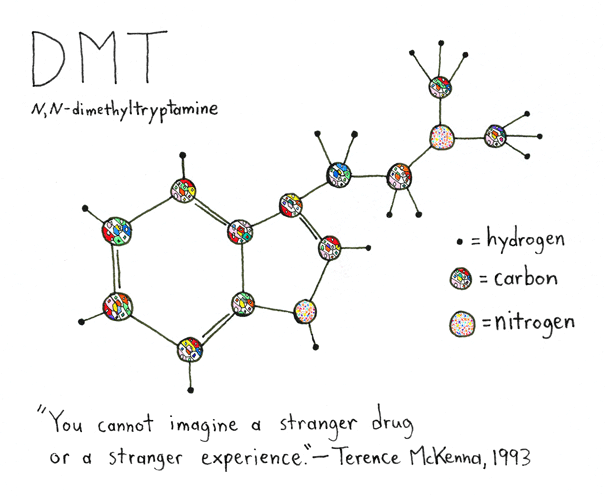

Scientists have discovered DMT, the Class A hallucinogenic, naturally occurs in the body, and may contain a clue to what happens when we die and why people see fairies

DMT (Dimethyltryptamine) is the most powerful hallucinogenic drug around. The class A psychedelic is so potent that under the 1971 UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances its manufacture is strictly for scientific research and medical use and any international trade is very closely monitored. But it also naturally occurs in the human body. Now a Senior Psychologist at Greenwich University, Dr. David Luke, is trying to undercover a link between DMT and ‘near death experiences’ to explain elves, tunnels of light and centuries old folklore. On July 8th he’ll talk about his research at an event in conjunction with SciArt collaboration Art Necro at The Book Club in London.

Tell me about yourself

I am a psychologist at the University of Greenwich and I teach a course on the psychology on the exceptional human experience, which looks at extraordinary phenomenon of human beings. It’s all about mythical experiences, psychedelic experiences, personal paranormal experiences, mysticism, spiritual experiences, those sorts of things.

I do research on altered states of consciousness and exceptional human experiences, including psychedelics, medication, hypnosis as altered states and the experiences people have in the states such as out of body experiences, possession, telepathy, and clairvoyance – all your usual stuff.

How did you end up focusing on DMT?

I’m interested in DMT is because of my interest in psychedelics and the phenomenology of psychedelic use. DMT is of particular interest because it’s an extremely powerful psychedelic substance. But what’s more interesting than that, is that DMT naturally occurs in many plants, animals and in humans. It’s endogenous, meaning it’s made within the human body. So it’s more than just a natural plant psychedelic – it’s in us. That makes it extremely curious.

Wait – we naturally produce DMT? Why?

We don’t really know. It was first isolated as a chemical about 100 years ago in various plants. For example in ayahuasca, (a hallucinogenic brew from South America) the other chemicals that were isolated in a plant were named telepathine because users reported telepathic experiences. DMT was later found to be naturally occurring in the human body, found in large quantities in the cerebral spinal fluid. It’s thought to be produced in the lungs and in the eye. It’s also speculated, but not proven, that it’s made in the pineal gland.

What’s the pineal gland?

The pineal gland is a weird organ. During the daytime it produces serotonin, which we know keeps us happy and buoyant, and at night the serotonin gets converted into melatonin. It’s also thought that the gland produces DMT, which is converted from serotonin because they’re similar, it just an enzyme that converts it. The gland is part of the brain’s structure, situated just outside in the spinal fluid in a cavity. It’s really interesting. Why would we have an extremely strong psychedelic substance being produced in our brains? What is its ordinary function in humans? It’s not very well understood, largely because there’s not much done into it. The initial speculation thought that it was perhaps responsible for psychosis, in that people with schizophrenia may have an overproduction of DMT. There was some research conducted into it in the 1960s, but that didn’t get any consistent findings. So that idea was abandoned. Shortly after that, the research with humans stopped because psychedelics became illegal. It didn’t really stop people from taking them, but it did stop researchers from reaching the affect in humans.

Recently, research has begun again. A pioneering medical doctor in the 1990’s called Rick Strassman , started injecting people with DMT as part of a medical research project. About 50 to 60 participants were given high doses and they reported some extremely bizarre phenomena. Approximately half of the participants on a high dose reported being in other worlds and encountering sentient entities, i.e. beings of an intelligent nature which appeared to be other than themselves. The experience was so powerful that participants were convinced of the reality of experience with these other beings. It poses some very interesting questions.

What do these beings look like?

The beings themselves took on various forms. Sometimes they took on the form of little elves or imps or dwarves, sometimes they’re omniscient deities, other times they’re angelic beings. But they’re specifically not humans. Rick Strassman also speculated that the DMT experience had a lot of similarities with what we know about the near death experience.

How is being on DMT similar to having a near death experience?

The near death experience is a type of experience syndrome, whereby people perceive themselves to be near death or in danger of dying. Typical experiences include the sensation of leaving the body, entering into a tunnel of light and flashbacks of their lives. People typically meet some kind of being, sometimes a deceased relative or a powerful other, like an angelic being. The being will tell them it’s not their time to die and that they should return. Then the person who’s having the experience will return back to their body. Sometimes it coincides with them being resuscitated if they are having a genuine near death experience, like a cardiac arrest.

Research has suggested that there is an overlap between that experience and the experience people have when on DMT. In that there’s often encounters with beings, out of body experience, life changing experience, which is often said of near death experiences. But there are dissimilarities as well.

Why are these experiences particular to DMT?

That’s a five and half million dollar question. It’s not well understood. Why do people have this reoccurring theme of apparently sentient entities? It could be that it’s a hallucinatory experience, and for some reason DMT triggers the sense of encountering another being. Or perhaps it’s a misfiring of the brain’s neural network that’s reasonable for those kinds of experiences ordinary.

But it’s curious that the experience occurs in the absence of any kind of objective sentient being in the presence of the person. The other thing is that people quite adamantly testify to the reality of the experience. They say it’s more real than this world. Although we can explain it as a neurochemical misfiring, people who have the experience typically feel dissatisfied with that explanation because it feels so real. But to say it’s a hallucination isn’t satisfactory either.

Hallucination is a bit of a waste basket term for odd experiences we don’t really understand or can’t explain. It’s just a label really.

What’s even more baffling is that people seemingly independently have similar types of encounters. They may not know about other people’s experiences of little people, elves, gnomes or dwarves.

We’ve found reports of them right back to the very first DMT experiments conducted by a psychiatrist in Hungary during the 1950’s. He first tested it on himself and then gave it to his colleague.They all reported the same thing.

My colleagues and I think these experiences aren’t culturally mediated. This is when people are primed to expect something i.e. elves and dwarves and so on, because they’ve heard about it. We think people have been having these experiences on DMT naively, ever since it was first isolated and taken by humans. There’s something about DMT itself which cultivates these experiences. We’re just not sure how or why.

So why do you think DMT is present in the human body?

Rick Strassman tried to use it as a way of explaining the near death experience. He suggested that what happens when you have a near death experience is that your brain releases its store of DMT into the brain and it’s this chemical release that gives the experience.

No one has done a particularly thorough job of mapping the classic near death experience to the classic DMT experience. People have attempted crude compassions but no one has looked at it closely. When you do there are some overlaps but there are a lot of differences.

Although the DMT experience broadly contains all the elements of a near death experience, near death experiences are not like DMT ones. You have the experience of being out of the body or a tunnel of light, like you have with DMT, but there are things we find in the DMT experience that we don’t find in the near death one, such as geometric patterns and alien and bizarre experiences, whereas near death ones are typically very earthly.

What’s more Interesting is if you look at the folklore in literature around 100 years ago. People documented verbal accounts of people who had experiences with pixies. Typically in the folklore literature there were most often associated with spirits of the dead, which has some alliances with the idea of DMT being related to near death experiences. How and why that is, that’s anyone’s guess really.

Are we close to finding any answers?

Scientifically it’s somewhat tricky. I’ve been researching in this area for about 10 or 15 years. DMT struck me as being extremely curious because there’s no other psychedelic we know of that naturally occurs in the human body. I mean the human neural system has endocannabinoids which are related to cannabis THC, but there’s a big difference between that and the presence of DMT.

What’s the role of DMT in the body and why do people have such extraordinary intense and bizarre experiences when they take it? Strassman’s theory is that the purpose of DMT is to help people transition from a living state to a post-death state, whatever that might be. That’s a quite ambitious speculation from a scientific perspective. Because you can’t really know what happens after death.

Strassman’s theory is that the purpose of DMT is to help people transition from a living state to a post-death state, whatever that might be.

Current mainstream scientific thinking is that the brain dies and consciousness ceases. New research and evidence is beginning to challenge that. If you’re looking at the near death experience research that’s going on, people are reporting having experiences of conciseness and conscious awareness even when there’s no apparent brain activity. When the heart stops beating for about 20-30 seconds, all brain activity that we can detect stops because the brain is starved of oxygen.

In theatre operations when people have had their heart stopped and the blood drained from their brain have reported conscious experience throughout the whole procedure, sometimes lasting an hour or more, during which there is no brain activity that we can detect. This challenges the notion that you can have no consciousness experience without brain activity. Now we can’t be certain that they’re actually having a consciousness experience, because we can’t be sure it’s taking place at the same time as their stops working. They could just conflate the experience when they recover brain activity. Or it could be that there are some parts of the brain that we can’t detect, which still remain active. But there’s no evidence for that. So we’re in peculiar territory here, scientifically speaking.

Do you think we’ll ever be able to test for signs of consciousness after death?

We always like to think we’ll have a better understating in the future and science does tend to progress but it’s quite a tricky area. Experimentally it’s very difficult. We’re not in a position to experimentally put people into a death state and see what happens. Although we can take note of people who have surgical procedure and are put into a state of clinical death.

We don’t even know if DMT exists in the pineal glands. We have discovered it in the pineal glands of rats, which are anatomically similar to humans. So there is possibility but we have yet to discover what the pineal glands’ actually function is. It seems to be important as a neurological transmitter on certain, little understood, nerotransmitter sites in the brain. It also seems to have important indications in the immune system. But the question remains why we have an extremely potent psychedelic chemical floating around in the human body. Can this account for spontaneous mythical and spiritual experiences?

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Why I’m planning my own funeral in my 20s

By Claudia Long

As someone in their 20s, I try not to spend too much time thinking about my own death.

And when it comes to actually planning for the event, it’s somewhere on my priority list between becoming the eighth member of BTS and holidaying on Mars.

But when a friend — citing my love of gardening — sent me a link to a new funeral home that can compost your body after you die, it sent me down a rabbit hole of caskets, wills and burial fees.

There were so many options to choose from, which for an indecisive person like me is straight up more stressful than the idea of actually dying.

I figured, why not save myself some worry and plan my own funeral.

So you’re dead, now what?

There’s quite a few ways to deal with a dead body in Australia but unfortunately composting isn’t one of them just yet.

There isn’t yet a facility providing the service here, so I’d need to get my corpse sent to the US, and while I’m all for sustainability, a logistical nightmare doesn’t seem like the kindest gift to leave my family.

So what do my options look like?

For most Australians, cremation is the way to go, with 70 per cent of people taking the literal dust-to-dust route.

For the rest, burial is the other most popular choice.

But modern spins on these old traditions are becoming more common, according to Griffith University death studies expert Margaret Gibson.

“The possibilities are much greater than they’ve ever been before,” Dr Gibson said.

“It’s another way of marking the finality and transitioning the body into another form. Some people find it a cleaner kind of ritual and more, I guess, more finite in that sense.”

But down the body-composting clickhole I found another option: natural burial

Death, naturally

Essentially, natural burial involves placing your remains in the ground in biodegradable coverings — at a slightly shallower level than other burials to allow for better decomposition — and letting nature run its course.

There’s no embalming, headstone or fancy coffins, to minimise impact on the environment.

So minimal is that impact, that when I went to check out my potential final resting place at Gunghalin Cemetery in Canberra, I didn’t even realise we’d reached the natural burial ground until cemetery staff pointed it out.

Dr Gibson said the natural burial ground’s ability to blend in could make it an appealing option for councils looking for more cemetery space.

“The difficulty for local governments getting approvals to have cemeteries is that there’s always that question of where are they going to be and are they going to be close to where people live,” she said.

“The thing about natural burial is that it creates kind of a multiple space environment.

“It’s much more about a green space than a death space.”

While the process isn’t quite as common as other types of burial and cremation yet, the idea itself isn’t new.

A number of religious and cultural traditions around burial call for shrouding the deceased, as is often done in natural burials, and burying the body without embalming treatments.

Putting all your eggs in one casket

Once I’d opted to be interred at the natural burial ground, it was time to rethink any plans for a big, classic coffin (what can I say, I love drama).

When it comes to what you’ll be buried in, there’s plenty to choose from: did I want a shroud? A cardboard coffin painted by my family and friends?

In the end, I decided to go with a simple wicker basket, with flowers on top if my family were ok with bringing some along from the garden.

I booked in for a formal planning session with a not-for-profit funeral home, thinking now that I’d decided where and how I wanted to be buried I was set! Ready to go! Totally, 100 per cent prepared!

Not. Even. Close.

Tender Funerals is currently based in the Illawarra, with plans to be operating in Canberra by the end of the year. So hopefully by the time I die they’ll have everything ready to go.

And when it comes to funerals, turns out there are details you need to have prepared.

The planning session went for almost an hour and there were plenty of questions that needed answering.

- Indoors or outdoors? Outside.

- Flowers? Yes, but nothing too fancy.

- Music? Sure, I’ll prep a Spotify playlist.

- Eyes open or shut? Eyes absolutely, 100 per cent shut (?!).

And that’s just the start.

It’s all a bit overwhelming and that’s before you chuck a sudden death into the mix rather than one that’s hopefully decades away — a good reason to write down some ideas, just in case.

While it’s not all that common to plan and handle a funeral yourself, there’s technically nothing stopping you.

“The funeral industry doesn’t want people to take control of it,” said Dr Gibson.

“You could actually authorise your family to be your own personal funeral directors if you wanted to, it’s just that no one thinks about that and it’s not part of the conversation.

“Part of what keeps the industry going is that people don’t really want to think about their own death, they don’t think ‘ooh how exciting’.”

Who needs to know?

A funeral plan isn’t very useful if discovered under a stack of papers years after you’ve died, so you should tell your nearest and dearest what you want them to do.

That could be in the form of instructions in your will, putting together a plan with a funeral home like I did, or jotting down a plan for your loved ones to execute — just make sure to tell someone where you’ve left it.

Cost-wise, even choosing a natural burial, without many bells and whistles, dying is pretty expensive, particularly if you want to have a funeral.

That cost, combined with the pressure and complications of figuring out the logistics, is pushing some to ditch the funeral altogether.

As long as your remains are dealt with, there’s no legal requirement for any funeral or ceremony to mark your death.

“There’s probably a number of factors, but certainly it’s cheaper, I think the cost of funerals is a real factor for people,” said Dr Gibson.

“In some cases, it can be because the nature of the deceased person, maybe didn’t want that and was not particularly into any kind of forms of ceremony or celebration of their life.”

But Dr Gibson said people may want to think of those left behind before instructing there be no funeral.

“I’m not sure whether in the long term that is necessarily a good thing because, you know, funerals are about recognising in this communal way that someone has died,” she said.

“It’s a symbolic act of that recognition, but it’s also connected to the capacity to be able to grieve.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Dying Differently

— Can Old Ways to Die Help Us Find New Ways to Live?

Changing grief rituals for a post-Covid world

By Brandy L Schillace

A procession makes its way along a high ridge in the mountains. Dressed in bright colors, a group of Buddhist mourners beat hand-held drums by turning them side to side in rhythm. The steady plok-plok is accompanied by the ringing of bells and the singing of chants that echo in the thin air of high altitude.

Above them, as if in expectation, soar a host of griffin-vultures. This slow-marching party and its feathered heralds head for a sacred cliff at the roof of the world; for this is Tibet, and this is a sky burial.

For most Westerners, the idea of leaving remains for hungry birds is unnerving. In the U.S., death tends to be clinical, tidy, followed by a viewing and funeral service at a place specially made for the purpose. Friends and relatives fly in, gathering together for grief, for remembrance, and often for a meal.

But the Covid-19 pandemic changed this. The pandemic and its virulence meant no gathering, no sharing. It meant attempting to process a funeral from afar, over Zoom. It meant being unable to perform those last basic rituals we’ve come to associate with saying goodbye.

What do these changes mean for us now and ongoing? I’ve been asked about this a lot in the past year — interviewed for Jodi Kantor’s piece on changing funerals for the New York Times, and speaking to NPR’s Tonya Mosley on Here and Now about how we can cope.

I think there is much to learn, in particular, from funeral traditions from other parts of the world. Funeral rites have been a part of human communities for a very long time —sky burial for around 11,000 years — but as a social practice, they can change as situations change. Looking at death and grief across cultures can provide a roadmap for coping with our strange new realities post-pandemic.

Sky Burial

I first encountered “sky burial” while writing Death’s Summer Coat. In Tibet, Buddhists have a tradition of ritually dissecting the dead into small pieces and giving the remains to waiting vultures and other carrion birds. The practice agrees with fundamental Tibetan Buddhists beliefs: the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, and living in harmony with nature.

The mourners began this particular day by washing and preparing the body, then wrapping it in colorful cloth. They sing and chant up to the ledges, where a special technician will dissect it for the waiting vultures. The body will, by these means, be broken down for easier consumption by the birds, whose lives will be enriched by the man’s flesh and blood. Scarcely anything will be left, and nothing wasted.

Dho-Tarap, Tibet is one of the most remote inhabited villages on earth at 12,000 feet. So this burial is also practical. Not all Buddhists practice sky burial. But you can understand why it is popular in the cold, tree-less mountains (with its frozen ground). You cannot burn a body with no fuel. You cannot bury it in hardened earth. At some point in their long history, the Tibetan Buddhists chose this method as the best means of disposing of the dead. Social traditions can be altered to meet the needs of the time, the place, and the circumstances of the people they serve.

The Dead at Home

During the Covid-19 lockdown, many of our traditions were interrupted. Weddings didn’t happen. Travel ceased. Lives were cocooned, as though wrapped in wool and put away for winter. But amid the seeming halt of everything else, death moved relentlessly forward. We lost loved ones, but often were unable to mourn them the way we wanted to. A wedding might be postponed; what if we could postpone a funeral?

One of the most unusual traditions I encountered during my research (apart, that is, from necrophagy), belongs to the Torajan people of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. They bury their dead in a variety of ways, sometimes hanging coffins from cliff-sides or interring remains inside of growing trees, or — occasionally — keeping them in the home, mummified.

Life among the Torajans actually revolves around death, and wealth is amassed throughout life in order to ensure a properly auspicious send-off at death. Raising money can be a lengthy process, and so a family embalms and stores the body in the home until the funeral can be properly paid for. Until the ceremonies are complete, a Torajan is not considered truly “dead,” even if the process takes years.

When the Torajan people lose a family member, perhaps a matriarch, there is grief; there is loss. But in order to mourn her properly (and celebrate her life and legacy), they must delay the funeral. The family will tell others that she is “sick,” and even symbolically feed and nourish her by setting a place at the table.

But when they at last have sufficient funds, an enormous celebration ensues — akin to the kind of work and cost that goes into some Western weddings. They also practice Ma’Nene, a ritual in which dead (now mostly mummified) relatives are disinterred, cleaned, and dressed in new fabric to be celebrated a second time.

Such practices may seem alien to Westerners, but I suggest that they offer reassurance and hope as well. If something has intervened to make the funeral of a loved one impossible in the moment, there is no reason it cannot be delayed to a later time — and no reason why it can’t be celebrated more than once. We may not have the remains among us, unless the person was cremated, but we still have the tangible memory of them that lives in each of us. Perhaps there may be new paths for our grief in the post-pandemic period.

Mementos to Grief

Some may be familiar with the concept of memento mori popular during the Victorian period as mourning jewelry made from the hair of a loved one. But a momento can be many things; a letter, a photo, an article of clothing, an heirloom. I remember walking through my grandmother’s house after her passing, feeling her presence as I touched even the most mundane objects: her favorite jelly spoon, her cast iron skillet. These pieces stand in for the body, and evoke memory through sight, smell, and touch. They can be important parts of grief ritual, too.

During dictator Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge reign in Cambodia (1975–1979) more than a million people perished from bloodshed and refugee conditions. Family members disappeared without a trace, children never returned home, and no one knew where the bodies were buried. This was particularly hard upon the Cambodian people, whose beliefs required that certain burial and post-burial rituals must be performed over the body. Otherwise, they feared the soul would wander and be lost, unable to reach the next spiritual level. How could this be possible among the burial pits of executed, unnamed victims? At a time of greatest tragedy, they had been denied their death rituals.

So, culture adapted. The Cambodian people created a new ritual, called chaa bangsegoul, explicitly to deal with genocide. Instead of chanting, in the moment of death, over the deceased loved one, the living may choose a photograph or something owned by the dead as a momento stand-in. With this connection to the departed, ritual chants are performed to help the wandering soul on its way, even years after the event. The Cambodian culture changed to make room for grief and death in a new way, incorporating a new ritual to heal over devastating losses.

Many during the Covid-19 pandemic also suffered devastating losses. Whole families have been plunged into grief, and some of us are mourning for those funerals we could never attend. Perhaps we can look at these at-first unfamiliar practices and think about how our own rituals can change to meet new circumstances.

What rituals might we evolve even now to find closure after the losses of the past year — and how might we re-celebrate life, and re-approach death, in the months and years to come?

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What to Do When a Loved One Dies — Checklist

Practical steps you need to take in the early days

by Leanne Potts

When people die, they leave behind a life that must be closed out. The funeral must be planned, bank accounts closed, pets rehomed, final bills paid.

When someone you love dies, the job of handling those personal and legal details may fall to you. It’s a stressful, bureaucratic task that can take a year or more to complete, all while you are grieving the loss.

The amount of paperwork can take survivors by surprise. “It’s a big responsibility,” emphasizes Bill Harbison, a trusts and estates lawyer in Nashville, Tennessee. “There are a lot of details to take care of.”

You can’t do it alone. Settling a deceased family member’s affairs is not a one-person task. You’ll need the help of others, ranging from professionals like lawyers or CPAs, who can advise you on financial matters, to a network of friends and relatives, to whom you can delegate tasks or on whom you can lean for emotional support. You may take the lead in planning the funeral and then hand off the financial details to the executor. Or you may be the executor, which means you’ll oversee settling the estate and spend months, maybe even years, dealing with paperwork.

To marshal the right help, you’ll need a checklist (see below) of all the things that need to be done, ranging from writing thank-you notes for flowers sent to the funeral to seeing a will through probate.

To Do Immediately After Someone Dies

Get a legal pronouncement of death

If your loved one died in a hospital or nursing home where a doctor was present, the staff will handle this. An official declaration of death is the first step to getting a death certificate, a critical piece of paperwork. But if your relative died at home, especially if it was unexpected, you’ll need to get a medical professional to declare her dead. To do this, call 911 soon after she passes and have her transported to an emergency room where she can be declared dead and moved to a funeral home. If your family member died at home under hospice care, a hospice nurse can declare him dead. Without a declaration of death, you can’t plan a funeral, much less handle the deceased’s legal affairs.

Tell friends and family

Send out a group text or mass email, or make individual phone calls, to let people know their loved one has died. To track down all those who need to know, go through the deceased’s email and phone contacts. Inform coworkers and the members of any social groups or church the person belonged to. Ask the recipients to spread the word by notifying others connected to the deceased. Put a post about the death on social media, both on your account and the deceased person’s accounts, if you have access.

Find out about existing funeral and burial plans

“Ideally, you had the opportunity to talk with your loved one about his or her wishes for funeral or burial,” writes Sally Balch Hurme, an elder law attorney and author of Checklist for Family Survivors. If you didn’t, she advises you look for a letter of instruction in the deceased’s papers or call a family meeting to have the first conversation about what the funeral will look like. This is critical if he left no instructions. You need to discuss what the person wanted in terms of a funeral, what you can afford and what the family wants.

Within a Few Days of Death

Make funeral, burial or cremation arrangements

• Search the paperwork to find out if there was a prepaid burial plan. If not, you’ll need to choose a funeral home and decide on specifics like where the service will be, whether to cremate, where the body or ashes will be interred and what type of tombstone or urn to order. It’s a good idea to research funeral prices to help you make informed decisions.

• If the person was in the military or belonged to a fraternal or religious group, contact the Veterans Administration or the specific organization to see if it offers burial benefits or conducts funeral services.

• Get help with the funeral. Line up relatives and friends to be pallbearers, to eulogize, to plan the service, to keep a list of well-wishers, to write thank-you notes and to arrange the post-funeral gathering.

• Get a friend or relative who is a wordsmith to write an obituary.

Secure the property

Lock up the deceased’s home and vehicle. Ask a friend or relative to water the plants, get the mail and throw out the food in the refrigerator. If there are valuables, such as jewelry or cash, in the home, lock them up. “You have to watch out for valuable personal effects walking out,” Harbison says.

Provide care for pets

Make sure pets have caretakers until there’s a permanent plan for them. Send them to stay with a relative who likes animals or board them at a kennel. The pet will be grieving, so be sure they’re with someone who can comfort them.

Forward mail

Go to the post office and put in a forwarding order to send the mail to yourself or whoever is working with you to see to the immediate affairs. You don’t want mail piling up at the deceased’s home, telegraphing to the world that the property is empty. This is also the first step in finding out what subscriptions, creditors and other accounts will need to be canceled or paid. “The person’s mail is a wealth of information,” Harbison says. “Going through it is a practical way to see what the person’s assets and bills are. It will help you find out what you need to take care of.”

Notify your family member’s employer

Ask for information about benefits and any paychecks that may be due. Also inquire about whether there is a company-wide life insurance policy.

Two Weeks After Death

Secure certified copies of death certificates

Get 10 copies. You’re going to need death certificates to close bank and brokerage accounts, file insurance claims and register the death with government agencies, among other things. The funeral home you’re working with can get copies on your behalf, or you can order them from the vital statistics office in the state in which the person died.

Find the will and the executor

Your loved one’s survivors need to know where any money, property or belongings will go. Ideally, you talked with your relative before she died and she told you where she kept her will. If not, look for the document in a desk, a safe-deposit box or wherever she kept important papers. People usually name an executor (the person who will manage the settling of the estate) in their will. The executor needs to be involved in most of the steps going forward. If there isn’t a will, the probate court judge will name an administrator in place of an executor.

Meet with a trusts and estates attorney

While you don’t need an attorney to settle an estate, having one makes things easier. If the estate is worth more than $50,000, Harbison suggests that you hire a lawyer to help navigate the process and distribute assets. “Estates can get complicated, fast,” he says. The executor should pick the attorney.

Contact a CPA

If your loved one had a CPA, contact her; if not, hire one. The estate may have to file a tax return, and a final tax return will need to be filed on the deceased’s behalf. “Getting the taxes right is an important part of this,” Harbison says.

Take the will to probate

Probate is the legal process of executing a will. You’ll need to do this at a county or city probate court office. Probate court makes sure that the person’s debts and liabilities are paid and that the remaining assets are transferred to the beneficiaries.

Make an inventory of all assets

Laws vary by state, but the probate process usually starts with an inventory of all assets (bank accounts, house, car, brokerage account, personal property, furniture, jewelry, etc.), which will need to be filed in the court. For the physical items in the household, Harbison suggests hiring an appraiser.

Track down assets

Part of the work of making that inventory of assets is finding them all. The task, called marshaling the assets, can be a big job. “For complex estates, this can take years,” Harbison says. There are search firms that will help you track down assets in exchange for a cut. Harbison recommends a DIY approach: Comb your family member’s tax returns, mail, email, brokerage and bank accounts, deeds and titles to find assets. Don’t leave any safe-deposit box or filing cabinet unopened.

Make a list of bills

Share the list with the executor so that important expenses like the mortgage, taxes and utilities are taken care of while the estate is settled.

Cancel services no longer needed

These include cellphone, streaming services, cable and internet.

Decide what to do with the passport

You have a couple of options on how to deal with your family member’s passport. You do not have to return it; you can keep it as a memento, with the stamps on its pages reminding you of past adventures. If you’re worried about the possibility of identity theft, mail the passport to the federal government along with a copy of the death certificate and have it officially canceled. If you want the canceled passport returned, include a letter requesting that be done. You can also request the government destroy the passport after it’s canceled.

Notify the following of your loved one’s death:

• The Social Security Administration: If the deceased was receiving Social Security benefits, you need to stop the checks. Some family members may be eligible for death benefits from Social Security. Generally, funeral directors report deaths to the Social Security Administration, but, ultimately, it’s the survivors’ responsibility to tell the SSA. Contact your local SSA office to do so. The agency will let Medicare know that your loved one died.

• Life insurance companies: You’ll need a death certificate and policy numbers to make claims on any policies the deceased had.

• Banks, financial institutions: If you share a joint account with your deceased loved one, you’ll need to notify the bank they’ve died. Most bank accounts carry automatic rights of survivorship, which means if your name is on the account, you have full access to the funds when your loved one dies. You become the sole owner on the date of your relative’s death. Most banks will require a death certificate to remove the relative from the account.

If the deceased person was the sole owner of a bank account, the bank will release funds to the person named beneficiary once it learns of the account holder’s death. Many banks let their customers name a beneficiary or set the account as Payable on Death (POD) or Transferable on Death (TOD) to another person. You’ll need to show the bank a death certificate to get the funds released. If the owner of the account didn’t name a beneficiary or POD, things get more complicated. The executor will be responsible for getting the funds to repay creditors, pay bills and divide funds according to the dead person’s will.

• Financial advisers, stockbrokers: Determine the beneficiary listed on accounts. Depending on the type of asset, the beneficiary may get access to the account or benefit simply by filling out appropriate forms and providing a copy of the death certificate (no executor needed). While access to the money is straightforward, there are tax consequences to keep in mind. You will be responsible for paying any taxes earned by the account once your loved one dies. Keep in mind, the tax burden could be significant on a well-funded investment account.

• Credit agencies: To prevent identity theft, send copies of the death certificate to one of the three major credit bureaus: Equifax, Experian or TransUnion. You only need to tell one of them, and it will tell the others.

Cancel driver’s license

This removes the deceased’s name from the records of the department of motor vehicles and prevents identity theft. Contact the agency for specific instructions, but you’ll need a copy of the death certificate. Keep a copy of the canceled driver’s license in your records. You may need it to close or access accounts that belonged to the deceased.

Close credit card accounts

Contact customer service and tell the representative that you’re closing the account on behalf of a deceased relative who had a sole account. You’ll need a copy of the death certificate to do this, too. Keep records of accounts you close and inform the executor of any outstanding balances on the cards. Credit bureaus, as part of their regular reporting process, will also send card issuers an alert that your relative has died. But if you want credit accounts notified faster, contact them directly. Be sure to cut up your dead loved one’s credit cards so they aren’t lost or stolen.

If the credit card account is shared with another person who intends to keep using it, keep the account open but notify the issuing bank your relative has died so the deceased’s name can be removed from the account. Destroy any cards with their name on them to prevent theft and identity fraud.

Terminate insurance policies

Contact providers to end coverage for the deceased on home, auto and health insurance policies, and ask that any unused premium be returned.

Delete or memorialize social media accounts

You can delete social media accounts, but some survivors choose to turn them into a memorial for their loved one instead. Twitter, Facebook and Instagram all allow a deceased person’s profile to remain online, marked as a memorial account. On Facebook, a memorialized profile stays up with the word “Remembering” in front of the deceased’s name. Friends will be able to post on the timeline. Whether you choose to delete or memorialize, you’ll need to contact the companies with copies of the death certificate. TikTok does not offer a memorial option for a deceased user’s account.

Close email accounts

To prevent identity theft and fraud, shut down the deceased’s email account. If the person set up a funeral plan or a will, she may have included log-in information so you can do this yourself. If not, you’ll need copies of the death certificate to cancel an email account. The specifics vary by email provider, but most require a death certificate and verification that you are a relative or the estate executor.

Update voter registration

Contact your state or county directly to find out how to remove your dead relative from the voting rolls. Here’s a state-by-state contact list. The rules vary by state. Some states get notifications from state and local agencies and will remove your dead relative from voter registration rolls automatically. States will also remove voters if a relative notifies them of the death. Depending on where your loved one was registered to vote, you may need to give notice of the death in writing, by affidavit or with a death certificate.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The US Civil War drastically reshaped how Americans deal with death

– Will the pandemic?

More than 1 million people living in the United States have died of COVID-19 during the past two years.

The numbers paint a clear picture of devastation, though they can’t capture the individual and familial pain of losing loved ones – which will no doubt transform many more millions of Americans’ lives.

The impact of this mass death on American society as a whole is less clear, especially since the pandemic is not over. While there have been a few moments of public remembrance – 700,000 white flags placed on the National Mall, and President Joe Biden’s brief words noting the “one million empty chairs around the dinner table” – the country is only beginning to grapple with the shared grief of so many deaths.

Instead, there is public discord surrounding those who died. In a country divided over basic facts about the virus, deaths have been exploited for political purposes, or wrapped into conspiracy theories.

As a scholar of religion who has studied the history of death in America, I am quite preoccupied with how the country makes sense of, honors and remembers the COVID-19 dead. The magnitude of death today immediately brings to my mind the event that killed the second-highest number of Americans: the Civil War.

My first book, “The Sacred Remains,” looked at the conflict’s impact on Americans’ attitudes toward death, during another period of extreme division and overwhelming loss of life.

Preserving the dead

Roughly 750,000 people died in the Civil War, or 2.5% of the country’s population at the time – the equivalent of 7 million Americans dying today.

The unprecedented death toll had profound consequences on American cultures of death for generations, particularly through the emergence of the funeral industry.

Throughout the 19th century, most Americans died, and had their bodies tended to, at home. Last moments with the corpse were with loved ones, who were responsible for washing and preparing it for the final rituals before burial, generally in local churchyards.

But the Civil War provided an opportunity for a game-changing development. Embalming was an innovative method of preserving bodies that allowed some Northern families to have their war dead retrieved from the mostly Southern battlefields and brought back to be buried in Northern soil.

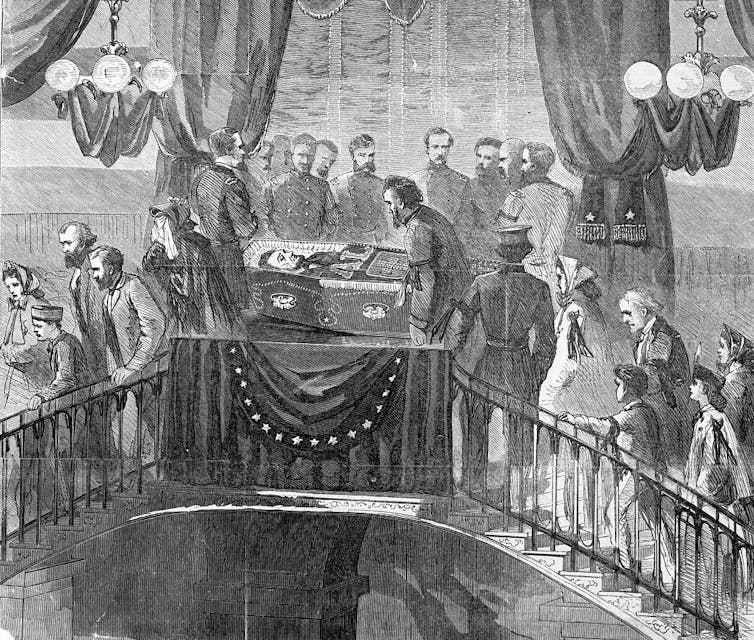

The display of President Abraham Lincoln’s embalmed body after his assassination was a pivotal moment in this transformation. His corpse was transported on a train from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois, with frequent stops in many Northern cities where it was put on display for grieving Americans.

As embalming became more common, it helped legitimize a new class of professional experts: funeral directors, whose homes became a mix of business, mortality, religion and their own domestic life. By the early 20th century, this new business had established a fairly standard American way of death, centered on the viewing of an embalmed body to bring a community together.

Americans’ relationship to their dead would never be the same. The intimacies the living had with the dead before the Civil War gradually disappeared, as funeral homes managed the care of more and more bodies.

Meaning-making

One of my intellectual heroes, sociologist Robert Hertz, wrote a famous essay about death and society in 1907. He argued that social groups represent themselves as immortal, capable of overcoming the death of any member. The community’s survival depends greatly on transcending death, so it transforms the dead into sacred symbols of group identity and social cohesion.

Hertz’s studies focused on death in small societies in Borneo. Yet his exploration of the relationship between the death of the individual and the life of the social group is pertinent now, in the context of the pandemic – as it was in the aftermath of the Civil War.

The victorious Union turned dead soldiers into symbols of the nation. Their deaths were seen as sacred sacrifices to preserve the country. For religion scholars, this is a clear example of American civil religion. In the U.S., civil religion is a patriotic culture that sees America as a sacred, exceptional country, built on shared ideals, myths and traditions.

But the Northern victors did not “control the narrative,” as we say these days. Indeed, a very striking and still-present counternarrative soon developed among the vanquished Confederates after the war. The losers built an alternative civil religious culture, what historians refer to as “the religion of the Lost Cause.”

For many white Southerners, the battlefield dead did not signal God had abandoned their cause but rather illuminated his support for values associated with the Confederacy – values the United States is still grappling with today. They saw the loss as a temporary setback, but believed that ultimate victory would come if they maintained some form of Southern cultural purity based on notions of racial, regional and religious superiority.

Looking ahead

The politicization of death is not uncommon in American history, particularly during times of profound social crisis. And since the start of the pandemic, the same has happened with COVID-19 victims.

Death during a pandemic is obviously different from death during a civil war. In both cases, however, it is difficult for a divided country to experience unity in the face of an enormous loss of life and to agree on what those deaths mean for the nation.

Unique aspects of the pandemic make national mourning, and united healing, even more complicated. For example, the virus has not taken an equal toll across the country. The death toll shows significant disparities among different economic and racial groups. And the need to prevent contagion has intensified the physical separation between the living and the dead, making some meaningful rites of mourning difficult or impossible.

Many communities have made efforts to commemorate the pain of the pandemic, such as through Dia de los Muertos, a Mexican holiday honoring those who have died. But there have been minimal efforts to help make sense of the deaths on a national level: to rally around a compelling public narrative about the tremendous loss of life and grief. It remains to be seen if Americans will eventually incorporate the losses into a unifying civil religion, or only use them to reinforce polarization.

One million dead and counting will certainly require more efforts, more reflection and more soul-searching to help American society overcome and indeed draw strength from this unimaginable number.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!