By Sarah Simons

[S]hould doctors do everything they can to preserve life, or should some medical techniques, such as cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR), be a matter of patient choice? Doctor Sarah Simons wades into the debate and argues that ‘do not resuscitate’ decisions are all about patients’ human rights.

Of all our human rights, the right to life is the one most often held up as the flagship, fundamental right: after all, without life, how can one learn, love, communicate, play or have a family?

The right to life is closely linked to the right to health. Under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which the UK has signed and ratified, states are required to “recognise the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”.

Protecting patients’ rights to life and health involves providing necessary life-saving treatment (known as resuscitation) if their life is threatened by serious illness or injury. It also involves enabling patients to live as well as possible for as long as possible: for example, by treating preventable diseases and encouraging people to adopt a healthy lifestyle. However, although many aspects of medicine and health are unpredictable, death is the one certainty for all of us.

Is There a Right to a Good Death?

In recent years, there has been much debate surrounding how healthcare practitioners should approach end-of-life issues with patients. A ‘good, natural death’ is increasingly recognised as a part of someone’s human right to life.

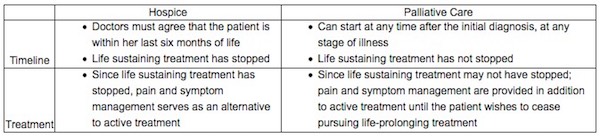

When healthcare professionals acknowledge that someone is approaching the final stages of their life, and no longer responding to life-saving treatment, treatment is not withdrawn, but instead, the goal is changed to treatment focussed on preserving the patient’s quality of life and managing their symptoms in accordance with their wishes. It’s important to draw a distinction between this and the ethical debate on euthanasia, which is altogether different from end-of-life care and natural death.

A ‘good, natural death’ is increasingly recognised as a part of someone’s human right to life.

Sarah Simons

This change of focus often includes completing a ‘Do Not Resuscitate’ (DNR) order, instructing healthcare teams not to carry out cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) when the patients’ heart and lungs cease to work. This decision is usually made on the grounds of pre-existing medical conditions and poor physiological reserve and frailty, which mean that CPR will not be successful. A DNR should always take into account the patient’s informed opinion on the matter, or at least their next of kin’s.

A DNR decision only refers to CPR. The patient can still receive treatment for related issues, such as antibiotics for an infection, and all other life-preserving or life-saving treatments can be given until the patient’s heart and lungs stop working. A DNR decision never means that life-saving treatment is not given – the purpose of a DNR is to allow the patient to pass away naturally and peacefully, with dignity and without traumatic medical intervention.

What Exactly is CPR?

Understanding the reality of CPR is vital to understanding why it is a human rights issue. CPR is used when someone has a cardiac arrest, which means they have suddenly stopped breathing and their heart has stopped beating.

CPR specifically refers to the chest compressions, electric shocks and artificial breathing technique used to stimulate and replicate the beating of the heart to pump blood around the body and the breaths taken to inflate the lungs with oxygen. This is effective when a sudden cardiac arrest occurs and someone’s organs stop unexpectedly, but the underlying mechanism of a cardiac arrest is very different from when the heart stops beating as part of the body’s natural decline at the end of life.

CPR is traumatic, undignified and usually unsuccessful in patients of all ages.

Sarah Simons

Sadly, despite Hollywood’s optimistic depictions of resuscitation, the reality is that CPR is often traumatic, undignified and usually unsuccessful in patients of all ages. CPR will not reverse years of gradually shrinking muscle mass, rejuvenate brains worn down by the steady decline of dementia, remove cancerous tumours or clear obstructed lungs weathered by years of COPD, which are often the underlying causes when someone’s heart and lungs have stopped.

CPR will cause bruising, vomiting, bleeding and broken ribs. CPR will render someone’s dying moments traumatic and undignified, and it will leave their friends and families with lasting memories of a failed, brutal resuscitation rather than a mental image of their loved one peacefully slipping away pain-free and asleep.

What Do Experts Have to Say About This?

Guidance published by the General Medical Council (GMC) in 2016 emphasised the importance of recognising patients’ human rights in relation to decisions about CPR and end-of-life care. The guidance recognised that “provisions particularly relevant to decisions about attempting CPR include the right to life (Article 2) [and] the right to be free from inhuman or degrading treatment (Article 3)”.

Article 3 of the Human Rights Convention specifically refers to the right to protection from inhuman or degrading treatment, and understanding the brutal, traumatic reality of CPR is a crucial consideration when thinking about DNR decisions. The GMC goes on to reference “the right to respect for privacy and family life (Article 8), the right to freedom of expression, which includes the right to hold opinions and to receive information (Article 10) and the right to be free from discrimination in respect of these rights (Article 14).”

The GMC guidance also highlights that the Human Rights Act, (which incorporates the Human Rights Convention into UK law), “aims to promote human dignity and transparent decision-making”, which should also be key concerns for doctors making decisions across all aspects of medicine.

Making the Right Choice For The Patient

Having open, frank discussions about CPR, and end-of-life decisions in general, enables healthcare professionals and patients to make informed decisions together. Doing so empowers patients to ask questions and insist that their rights are respected. It gives patients time to talk to their loved ones about what’s important to them, including any religious considerations, before their health deteriorates to a point where these conversations may not be possible.

Having open, frank discussions about CPR … enables healthcare professionals and patients to make informed decisions together.

Sarah Simons

Avoiding these conversations, while perhaps understandable given that no-one likes to think of their loved ones dying, means that important questions may not get asked and the patient’s wishes may go unheard. Making decisions on CPR and other practical matters is important, but so is acknowledging that someone wants to spend their last days eating mint chocolate chip ice cream at home listening to a specific Eva Cassidy album whilst surrounded by their pets and children.

As the NHS turns 70 later this year, and continues to navigate the challenges of an ageing population, conversations about end-of-life care are more important than ever before. Grief and bereavement are difficult, emotionally charged topics of conversation, but death is a normal human process. Taking the opportunity to talk about what we want at the end of our lives empowers us to make informed decisions and ultimately help all of us to die well one day.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!