A UCLA librarian on why you’ll want to read about them

By Leslie Pariseau

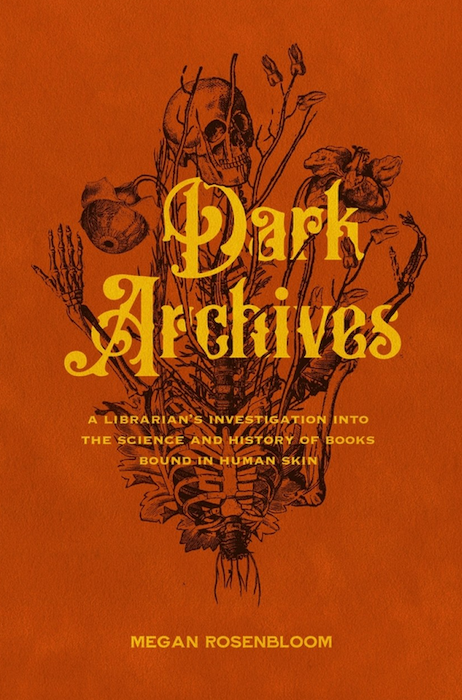

That a librarian has written a book about rare leather-bound books and a major literary imprint has published it is a triumph for bibliophiles everywhere — especially when you consider the source of the hide. “Dark Archives,” a deep dive into the history and mechanisms of sourcing, tanning and binding human skin into books, won’t be everybody’s cup of tea. But if you take comfort in reading Stephen King and Shirley Jackson on a stormy night or watching medical procedures on YouTube or you were the kind of kid who stole off to the occult section of the library (130 in the Dewey Decimal System, if I remember correctly), then Megan Rosenbloom’s strange history might be for you.

With sincere curiosity and clear-eyed analysis, Rosenbloom, a librarian at UCLA with a specialty in the history of medicine, unfurls the stories of the binders of the skins and their previous inhabitants: Mary Lynch, a young Irish widow who in 1868 died of trichinosis in a dreary Philadelphia hospital, her thigh skin saved in a chamber pot for decades; a Civil War soldier whose skin was stolen by Dr. Joseph Leidy and eventually became the binding for his “Elementary Treatise”; the highway robber George Walton, who planned for his own transformation into two books after his execution in 1837.

Over Zoom Rosenbloom jokes that she didn’t set out to be the “human skin book lady.” But her interest in rare books, combined with an early job in a medical library, led her down a winding path. “The things that I learned were just so shocking,” she says. “You mean medical students used to literally dig up graves and steal bodies, and their teachers were pretty fine about that?” Indeed, a good deal of “Dark Archives” engages with questions of consent around human bodies, especially during and after death — down to the most banal-seeming of our organs.

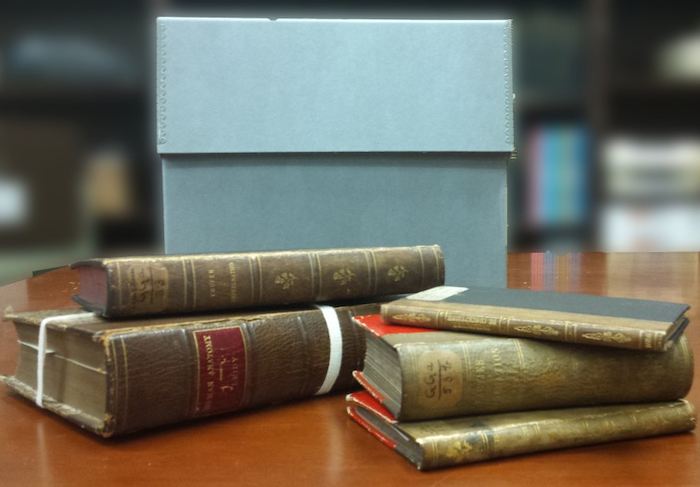

Growing up in a working-class Irish Catholic family in Philadelphia, Rosenbloom was attracted and repelled by “darker things” from an early age. This specific curiosity was first piqued in 2008 as she wandered around the Mütter Museum at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, which houses (among other bodily obscura) Einstein’s brain and a chunk of John Wilkes Booth’s vertebra. Rosenbloom came upon a case of leather-bound books whose display text claimed they were made of human skin — via a process called anthropodermic bibliopegy, practiced by 19th century doctors who wanted to give their own collections a special touch.

“A dead person’s skin had become a by-product of the dissection process,” Rosenbloom writes, “like a piece of animal leather after a butcher’s slaughter, harvested solely to make a doctor’s personal books more collectible and valuable.” Imagine a veterinarian keeping her feline patients’ hides and then covering her most prized medical books with them — except, in this case, the veterinarian would also be a cat.

In earnest pursuit of answers, Rosenbloom formed the Anthropodermic Book Project, which sets out to test as many books purported to be bound in human skin as possible. So begins her jaunt across through the U.S. and Europe to harvest samples. Rosenbloom’s project takes her to the library at the Los Angeles County Medical Assn., the site of a book supposedly bound in the skin of a white man captured by Native Americans; to Harvard, whose library holds not one but two prospects; to Cincinnati, home to a copy of Phillis Wheatley’s poems bound in 1934; and elsewhere, with often surprising test results.

Her travels extended to other relevant sites, from an old-fashioned tannery in upstate New York to understand the leather-making process to a Cleveland nonprofit dedicated to preserving tattooed skin once its (consenting) owner’s soul has departed their earthly vessel.

Rosenbloom is well aware that morbid curiosity can read as glibness. “The book walks a line,” she says, acknowledging the timing of the book’s release, in a year of multifarious horrors, with characteristic good nature. “I thought it was effective to have a guide because you should have someone you can trust.”

The author earns that trust. The result of Rosenbloom’s probing travelogues, lively histories and deep study of book stewardship is an incongruously bright-eyed view of a subject that, in the hands of another scholar, might be either plodding or gruesomely sensationalistic. The true story of how people became books is surprisingly intersectional, touching on gender, race, socioeconomics and the Western medical establishment’s colonialist mindset.

“Every time I tried to research a book, I would almost always find a doctor involved,” Rosenbloom says. “And the sort of disconnect between the way our society views doctors and then how this got done … is fascinating to me.” She says she spent time with texts like Ruth Richardson’s “Death, Dissection and the Destitute” to understand the rift between famous male doctors and the patients they treated: “People who didn’t have access to assert themselves or have agency around their bodies. What of them? It’s a harder story to tell.”

“Dark Archives” confronts the myth of Nazis turning human skin into gruesome objects, concluding the infamous lampshade (whose existence remains unproven) had become “an outsize emblem of the brutality of the Nazi regime.” She turns this conflation of history into an ironic twist on the banality of evil: “It’s easier to believe that objects of human skin are made by monsters like Nazis and serial killers, not the well-respected doctors the likes of whom patients want their children to become someday.” More than a tromp through a bizarre subset of bibliophilia, “Dark Archives” is a truth-telling expedition.

Rosenbloom’s nuanced approach is intertwined with her work as the cofounder of the Death Salon, an organization whose mission is to “[encourage] conversations on mortality and mourning and their resonating effects on our culture and history.” Styled after an 18th century salon, the event series is part of the Order of the Good Death, a group that works to promote the death positive movement — which aims to destigmatize dying.

“Basically everything that you take for granted and think is normal around death is totally culturally relative,” says Rosenbloom. She remembers having “a seed of fear” planted after attending an uncle’s funeral around 11, observing family members as they approached and retreated from the open casket. Eventually, she understood the necessity of confronting her own anxieties around mortality from an intellectual perspective. “I’m a bit of a control freak, anxious person, and if there’s something I can do or if I can learn about things and try to understand them, that helps with the anxiety thing.”

In many ways, “Dark Archives” feels like an extension of Rosenbloom’s death positive work, urging us to confront not just what happens to physical bodies after they die but the memory of people who occupied them — and a society that has systematically brushed them aside. “We can’t go back in time and stop anthropodermic books from being created,” writes Rosenbloom, “but since they exist, they have important lessons to teach us — if we’re willing to reckon with their dark past and all that it tells us about the culture in which they were created.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!